This year, Nu Goteh, Alice Grandoit, and Marquise Stillwell launched Deem, a biannual journal that approaches design as a social practice. In a conversation posted on the journal’s website, researcher Larenz Brown said, “I think Deem is for people who don’t always see themselves represented in media in a way that’s satisfactory. It’s for people who want to reclaim their rightful place in design conversations. It’s for people who have felt excluded from things that they feel deeply about.”

The journal’s first issue, “Designing for Dignity,” came out in print earlier this year and featured writer and facilitator adrienne maree brown on its cover. In an interview inside, Grandoit and brown discuss brown’s work facilitating discussions in community-based organizations. Grandoit encourages brown (and readers) to see that work as an integral part of the design process, one that shapes how communities plan and use space.

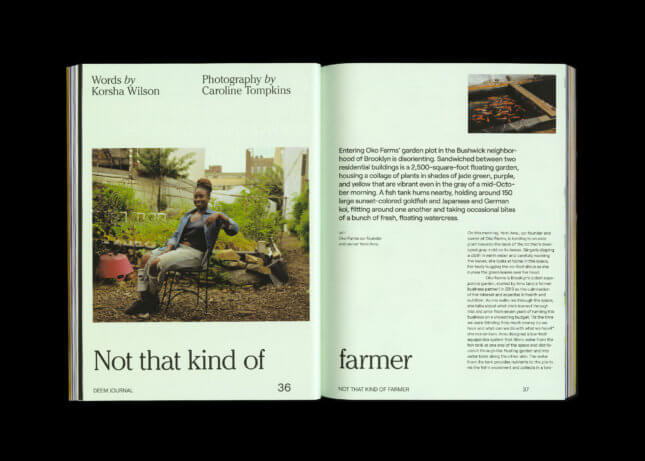

That mindset, that design is an expansive process that involves more people than professional architects and designers, informs the rest of the issue. In other articles, planning and geography scholar Hilary Malson writes about community land trusts as a tool for Black liberation; Grandoit and Goteh interview University of Southern California School of Architecture dean Milton S. F. Curry about the meaning of social practice; Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski of Pittsburgh-based WAI Architecture Think Tank analyze social responsibility in architecture; and food writer Korsha Wilson profiles “Brooklyn’s oldest aquaponics garden.” It’s an energizing mix of topics, voices, and approaches, all richly illustrated in a crisp, colorful layout. In May, AN’s managing editor, Jack Balderrama Morley, talked to Goteh, Grandoit, and Stillwell about the journal and how design can better serve cities and the people who live in them.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The Architect’s Newspaper: How do you think about the audience for Deem?

Nu Goteh: It’s an intersection of people who are active in various design practices, but we’re also trying to bring people who don’t consider themselves designers into design-based conversations. Which is fairly broad—but there are so many people who are interested in design but feel like they don’t have a voice and may not have the power to change things in their world. We’re trying to say that there are ways and tools that you’re capable of using, but you just haven’t been presented with them. Part of the editorial approach is to highlight different voices within different design practices to be able to reach beyond design and pull in “non-designers.”

Alice Grandoit: There are a variety of publications that touch on design in a way that can be engaging, but I think a lot of them are exclusive to people who might be trained designers. I had to question if there were other points of view that weren’t being considered or other people who were realizing work that reflected more of my environment.

Marquise Stillwell: Alice drives a lot of editorial. There are a lot of missing voices in what you consider mainstream design and architecture. The process to become a designer or architect is long, and it has been dominated by one voice: older white men. Setting a wider net is not only strategic but it’s also necessary to capture the types of voices that have been missing.

Even when I have seen other voices within design magazines, they have been included in a way that is very elementary or treats them as novelties. Theaster Gates is a good example. Because of his schooling and because he’s an artist, his narrative around innovation has helped to elevate other voices, but if he didn’t have that education or if he didn’t have that pedigree, publications would probably say, “Oh, this is some guy from the South Side of Chicago pulling a bunch of bricks and wood together. This is something that’s kind of cute and fun, but it’s still South Side Chicago, and it’s not really high art, but it’s cool to have as design porn or something that’s cool in a photo just to say that we’re expressing something.” We’re challenging that.

You’ve discussed before how Deem is about building more thoughtful conversations in design by listening to communities and emphasizing that design is a back-and-forth process involving many people. So much of design now, though, seems to be about image and oriented toward Instagram. Do you think design could use a redirection?

MS: Design fell in love with itself and forgot why it was actually a practice that we all love. We are trying to get back to what it means to design for people. What does it mean to design for humans and not just design to make shiny objects and the next thing that you can put on Instagram? I think design’s about people, and it’s really difficult sometimes to actually talk about people because we’re in a system right now where people don’t matter. We can see it in our political system, and I do believe that we are pushing against that in the right direction because people are saying, “Hey, I matter! What about me?”

Design fell in love with itself and forgot about the people.

AN: Looking forward, it can be hard to be optimistic. Are you all optimistic about the future of design?

NG: I’m optimistic. Alice and I were having a conversation with a young person who felt like, “Man, I never saw myself as a designer, and it wasn’t until I started entering different spaces that I realized that the work I had been doing and then facilitating is design, in a form.” And that person was excited that Deem was representing a space for that. I’m excited to see more people like that realizing the potential of design from their own perspectives.

AG: I’m interested in that and then also design returning to being a deep listening to the wisdom of our environments. There’s a lot of knowledge that exists around us in nature that I think is really coming to light now, and I’m hoping that we can tune back into that and let design feel a little more intuitive and driven by the wisdom that we all have.

MS: I do see that there is a growing mindset that in order for design to survive, it has to have diversity in thinking. Design has to have a diversity of lived experience for design to actually be what it’s supposed to be, and this is why I go back to the idea that design fell in love with itself and forgot about the people. It’s not just the people we’re designing for, but it’s the people participating in design that matter. That’s what makes me excited about our field and our future.

I’ve seen criticisms of “design thinking” lately, particularly in urban planning, where outside “experts” drop into a city and use design thinking in a top-down way to rework the fabric of a city. Do you think there is a way for design thinking to move past that criticism?

MS: I think the big point that you’re reaching for is that when you think about simple things about culture you start to do ethnography work. It’s very challenging if the person who’s doing the research has no understanding of what the culture they’re studying represents and dismisses that there’s even the existence of a culture in a neighborhood. We have to bring in individuals who have the tools to understand.

NG: In my experience, the best designers and the best strategists don’t really even see themselves as designers or strategists. Where I find value is in filters. We all have filters by way of our lived experiences, and you can have all these frameworks and different research methods, but then once you get that raw data, that raw data has to be synthesized. And the way that you synthesize it has to go through the filters of your lived experience. Design thinking can only go as far as the people participating in it, so without having a diverse enough group of people with lived experiences and different filters, you start to get the same answers, and it doesn’t really matter how many different processes you go through—you still have the same output. Part of the solution is to get different people with different filters to leverage existing processes, but then also create their own processes and be able to share those processes, so that then we start to get nuanced output.

MS: The other thing is that design has tried to use traveling or bringing in experts as a proxy for that. But you can’t just go and travel and experience [one place or city] and believe that you’re an ethnographer, that you’re actually going to inform how [another place or] city is going to be built based on the fact that people who live there resemble the people you traveled to go see. You actually need to bring those people into that process from the beginning, and they need to be a part of the tools; they need to be a part of the framework to actually exercise the best solution. So, that’s the next step of where design has to go.

Do you all have any thoughts about how Deem could change the world of design or change the world more broadly?

MS: We’re continuing to give permission to people who never saw themselves in a certain way. They have the right and the responsibility to step into their gifts and to shine. We see this represented in hip hop magazines from the 1990s where kids were finally seeing themselves represented in a positive manner and were starting to see that they were allowed to have a voice, and you can see how hip hop has since taken over the globe as an important narrative of dissent and questioning. Design has that same power, and right now we don’t have that journal or magazine or platform for designers of color that gives us permission to actually stand forward and be responsible for our gifts and be accountable for those gifts and really be strong in those gifts.

AG: I see Deem being at the center of this moment in which we are opening design to more players, thinkers, and doers. Deem is a space in which people can see themselves through the lens of design and where people can be empowered to enact change within their lives and communities.

NG: We’re setting out to empower people to feel that they can be a catalyst for change, that they have the ability, the mindset, and the lived experience to enact the change that they want to see.