Christo, the artist whose large-scale, environmental sculptures redefined the field of public art, died of natural causes last Sunday at his home in New York City at the age of 84. He was preceded in death by his partner in life and art, Jeanne-Claude, who passed away from complications of a brain aneurism in 2009. They are survived by their son, Cyril Christo, a wildlife photographer.

Born Christo Vladimirov Javacheff on June 13, 1935 (a birthdate he shared with Jeanne-Claude) in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, Christo moved between Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Austria before relocating to Paris in 1958. There he met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon with whom he would permanently settle in New York in 1964. Christo’s earliest sculptures consisted of wrapped objects or “packages,” which drew the favor of critics following the development of the Nouveau réalisme movement in France (a group approximately parallel to the American Pop artists of the 1960s). The couple began staging public artworks while living in Paris, notably installing Iron Curtain: Wall of Oil Barrels on June 27, 1962, during Christo’s solo exhibition at Galerie J (the GDR had erected the Berlin Wall the previous year). Comprising 204 stacked oil barrels that barricaded the Rue Visconti, the work was installed for only eight hours before police ordered its removal.

(Jeanne-Claude)

Governmental intervention and bureaucratic mediation would become a primary aspect of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s public art projects, and they came to consider these influences as features of the work just as much as the final physical installation. Such works as Running Fence (1972–76)—a two-week installation of a 24.5-mile-long sculpture in the countryside north of San Francisco—were often a result of years of planning, as the artists moved through the necessary channels to obtain all manner of permits, design approvals, and the blessing of local residents who initially opposed the work’s realization. Similarly, the pair made their first bid to install The Gates (1979–2005) in New York’s Central Park in 1981, but the project was rejected by the city’s parks commissioner Gordon J. Davis in a lengthy written statement, a setback both later integrated into the work; indeed, the artists took a holistic approach to their public works, documenting each delay or advancement and selling preliminary drawings, models, and other preparatory objects to finance each project free of outside investments.

(Wolfgang Volz)

Their body of work encompassed undertakings that ranged from the modest, such as the gilding of the footpaths in Kansas City, Missouri’s Loose Park with gold nylon fabric in 1978, to the monumental, exemplified by the wrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin in 1995. The latter project took more than twenty years to realize, as the political tensions of the cold war stymied the artists’ attempts to gain the necessary approvals and public support. Temporariness and interaction were primary aspects of their practice as they continually sought to create art accessible and inspiring to all who engaged with it. While some art critics refused to take their projects seriously, dismissing the work as repetitive and lacking in intellectual merit, all agreed that the pair were non-conformists who radically expanded the possibilities for what public art could achieve.

(Wolfgang Volz/©1978 Christo + Wolfgang Volz)

The immense public popularity of their works allowed for their realization in countries across the globe, including a fleet of 3,1000 outsized umbrellas installed in valleys outside of Tokyo and Los Angeles; a mile-high curtain draped between two ridges of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado; 200-foot-long panels of floating fabric radiating off islands in Florida’s Biscayne Bay; a million square feet of erosion-control fabric wrapping the coast of Little Bay, Sydney; fabric-covered piers connecting the island and shoreline of Italy’s Lake Iseo and, most recently, The London Mastaba, a glacier-like sculpture constructed from oil barrels and set adrift on the Serpentine Lake in London’s Hyde Park in 2018.

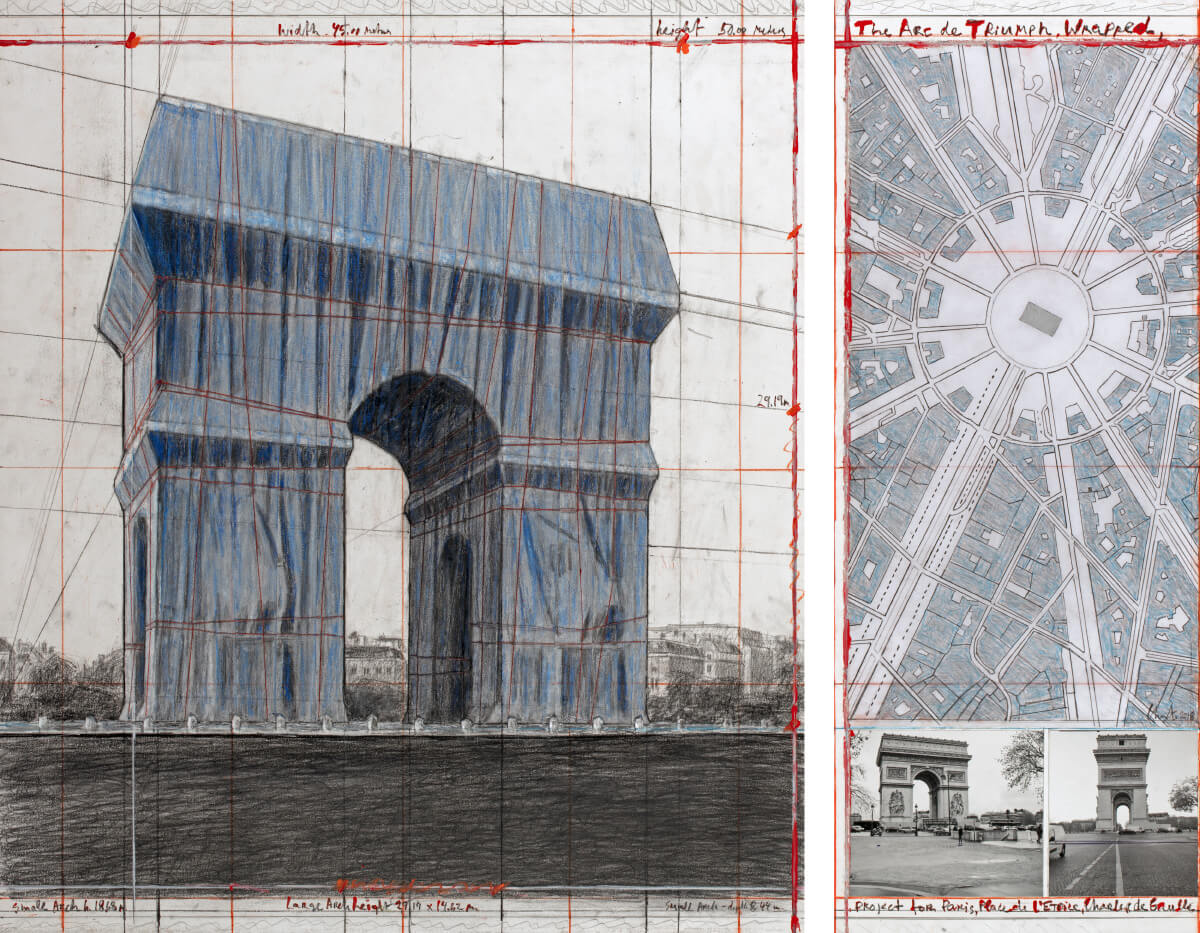

Gaulle (2018). While the French monument was originally supposed to be wrapped in April of this year, the novel coronavirus pandemic pushed the opening to 2021.

(André Grossmann/© 2018 Christo)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s 1975 wrapping of the Pont-Neuf in Paris will be the subject of an exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou, currently slated to open July 1. The artists always insisted that their works continue to be realized after their death, and one major public project is still on track to open in September of next year: The Arc de Triomphe in Paris will be wrapped according to plans originally conceived in 1962. The sculpture will consist of iridescent blue fabric held against the monument to revolution with crimson rope—a fitting tribute to the iconoclasts and their many triumphs.