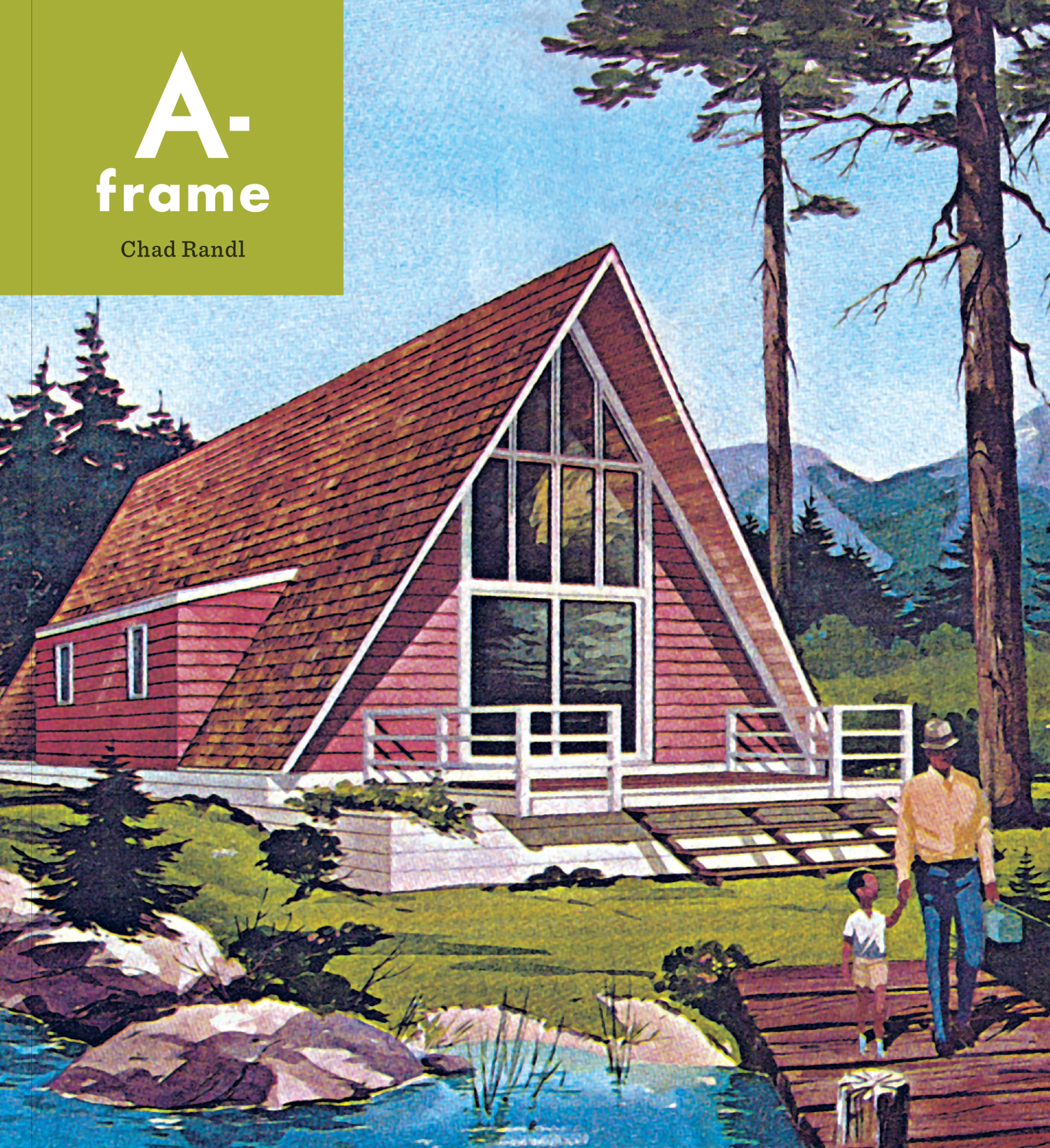

When Chad Randl’s A-Frame, a deep-dive into the architectural style that served as an enviable yet attainable postwar emblem of a life lived more leisurely, was first published by the Princeton Architectural Press in 2004, the national love affair with vacation homes featuring steeply angled rooflines and limited square footage was in a dormant phase, their popularity having peaked decades earlier.

At the time, the premiere of Mad Men, a cultural touchstone that spurred a fervent obsession with anything and everything associated with midcentury modern design, was still a couple years away. Serious interest in petite-sized homes was still incubating.

“Both were trends within the architecture and design and preservation communities back in 2004 but they have become mass-market phenomena in the 16 years since,” explained Randl to AN of what has changed in the years since A-frame was first published. “The other important difference is the rise of social media that allows people to share ideas and favored designs in ways that spread rapidly, efficiently, and without the mediation of experts or authorities.”

Once dismissed as outmoded, inefficient, and grandparent-y relics of a bygone era and widely abandoned in favor of resort communities and timeshare condominiums, A-frames are now—thanks in part to the above factors—a hot commodity again. And as such, Randl’s book, long out of print and difficult to find with used copies going for a pretty penny, has also returned for a highly-anticipated second edition.

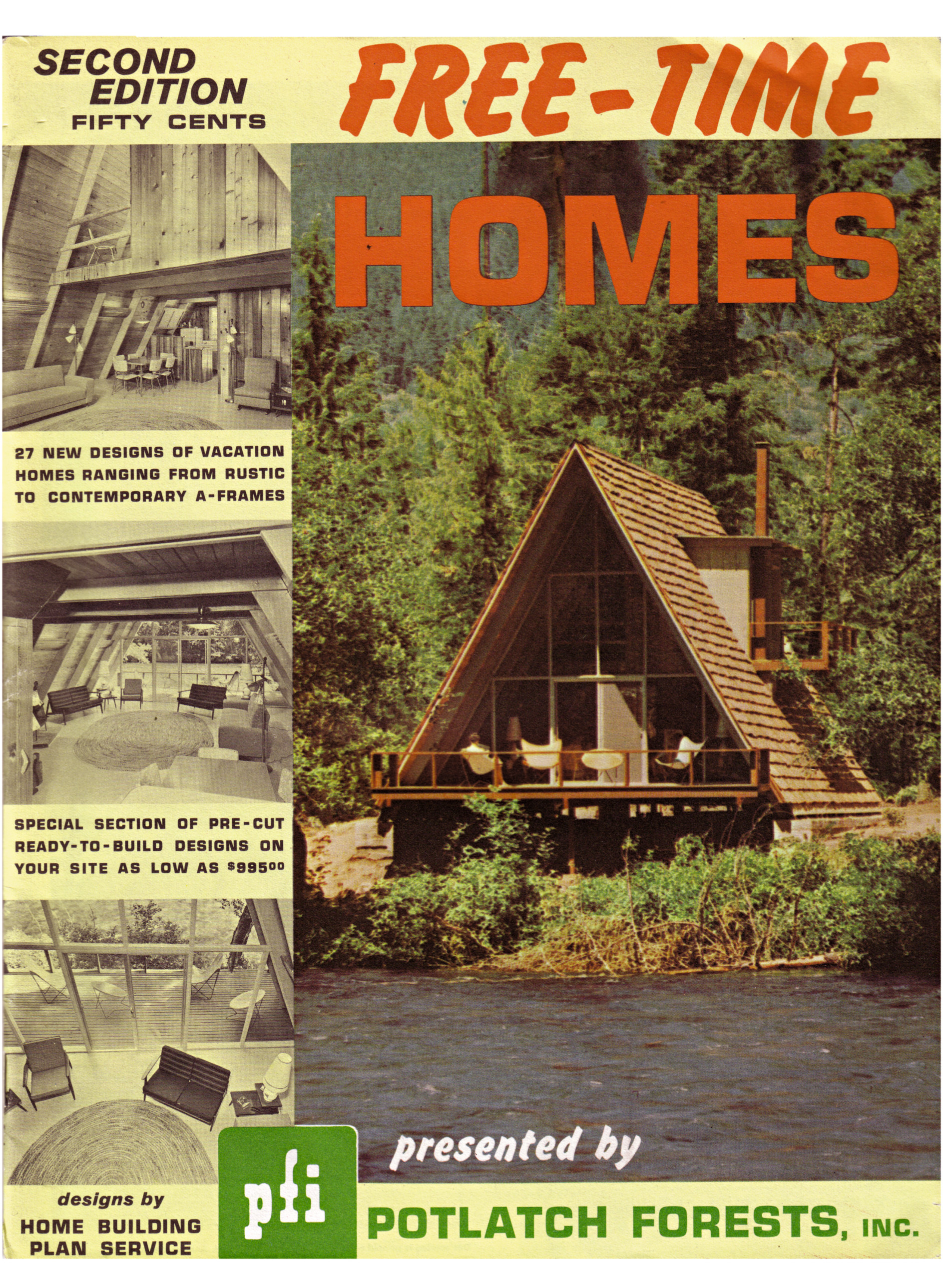

Rereleased last month just in time for summer reading, A-frame not only details the origins of the style but also includes building plans and exhaustively researched information about the top industry players in different regions during the A-frame’s 1950s-60s-era heyday; European counterparts; the style’s erstwhile status as an all-powerful marketing tool; and an entire chapter dedicated to the A-frame’s once-widespread commercial usage. “The pitched roof functioned as a billboard easily seen along the highway and standing out on cluttered commercial strips. Its visibility and quirkiness attracted attention. Attention meant patronage, patronage meant sales,” said Randl.

In the below preface to the new edition, Randl goes into further detail as to what has changed over the past decade-plus and what the future might hold for the humble, beautiful, and unusual A-frame.

A-Frame, Second Edition

Chad Randl

Published by the Princeton Architectural Press

MSRP $29.95

When A-frame was published in 2004, triangular buildings drew little notice. They could still be found along ski slopes, shorelines, and commercial strips around the world, but to many they were dated remnants of a bygone postwar era. Buyers in desirable resort areas routinely tore down A-frames, considering them ill-suited to both contemporary tastes and the valuable land beneath them. Soon after the book came out, for example, new owners demolished the 1955 Squaw Valley A-frame that is featured in the book’s introduction, replacing it with a much larger and more conventional vacation home.

Less than a generation later, the A-frame has undergone a reconsideration. With its legacy tied to nostalgia for postwar design and its attributes matched up with new attitudes, more A-frames are being rehabbed and fewer are being replaced. Renewed interest in the A-frame owes much to its association with what has come to be called mid-century modernism, a celebration of postwar expressive and minimalist forms from Eames furniture to Eichler homes. Beginning in the early 2000s, designers, furniture retailers, and magazines promoted this aesthetic and adapted it to twenty-first-century lifestyles. After decades in the wilderness, postwar A-frames—inviting and elegant—returned to respectability within high-end design communities. At the same time, the diminutive size, rustic, often do-it-yourself construction, and off-the-grid location of many postwar A-frames has endeared them to those exploring alternative ways of living. The tiny house movement, rooted in the 1960s and 1970s counterculture and influenced by subprime mortgage and affordable housing crises, sees the A-frame as an appropriate form of modest, customizable dwelling.

Mid-century modern enthusiasts, tiny house and “cabin porn” proponents, and other admirers disseminate their favorite triangular building examples through social media on a scale previously unimaginable. Japanese architect Shingo Niikawa and his partner, Mizuho Niikawa, for example, have used their digital channels to share findings and photographs from a six-month trip to visit thirty A-frames in seven countries. Their research provided information the couple is using to build their own version on land that they recently purchased overlooking Mount Chokai in Yamagata, Japan.1

A growing number of postwar A-frames, including those by Wally Reemelin and David Hellyer, have been rehabilitated. Some treatments are decidedly retro evocations of the A-frame’s heyday with shag rugs and period furniture; others are updated with stone countertops and finished walls. A-frame makeovers in Dwell and in one of the A-frame’s most reliable promoters, Sunset magazine, have been followed by those in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Curbed.com. Photographer Ben Rahn’s 2018 book The Modern A-frame featured rehabilitated designs alongside recent constructions. Surviving A-frames have also been included in guidebooks and historic resource surveys from Oregon to Aspen, Vermont to the Adirondacks.

When triangular buildings faded from popularity in the 1980s sellers avoided the term A-frame. Today they again trade on the A-frame name, noting its history and important figures. In his listings, Oakland-based real estate agent Chris Olson highlights examples attributed to Wally Reemelin, “one of the designers credited with the creation of the modern A-Frame form [whose] trademark structures are found throughout the Bay Area.”2 So (at least in some parts of the country) pedigree and provenance enhance the value and marketability of A-frames—a “Reemelin” is to the A-frame what an Eichler is to Bay Area mid-century-modern tract housing.

Existing and rehabbed A-frames from the postwar era are joined by a growing number of newly constructed versions. Four of the A-frames visited by the Niikawas during their worldwide tour were built in recent years. In 2018, architect Nils Luderowski developed several as-yet unbuilt designs for A-frames with details typical of Adirondack Great Camps and recreation architecture. Those interested in A-frame plans and kits also have more options today than in 2004. David Hellyer’s plans discussed in chapter four and included at the end of the book are still available online. In 2019, the Everywhere Travel Company, an online purveyor of tiny home kits and nomadic living experiences, began offering their “Ayfraym” model. Customers could purchase just the drawings or a DIY package for $149,000 that featured parts (including paint, appliances, and smoke detectors) for a complete house delivered in a forty-foot shipping container. Enthusiasts can also weekend in surviving triangular motel units or rehabbed, retro-styled A-frames (with butterfly chairs and new metal fireplaces) via online rental services like Airbnb or Vrbo.

Looking back, there are many different ways to tell the A-frame’s story and to bring things up to date. It is tempting to revise assertions about one iteration being the earliest or another being especially significant and influential. Additional examples (passed on the roadside or passed along by readers and friends after the book was first published) could be included: the A-frame constructed at Riverside Raceway in California to house a four-lane slot car track, the 1968 country retreat in Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico, designed by Howard Besosa, the house boat in Sausalito, or the hundreds built in the 1980s near Antelope, Oregon, by followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. But perhaps it is best to let this little book stand as written, capturing a moment when A-frames remained underappreciated and largely forgotten. A few years hence they may return again to disfavor and the attention they are receiving today may prove to be just another brief high before another fall, like a sloping line from floor to roof peak and back again.

1 Mizuho and Shingo Niikawa, interview by the author, 27 November 2018.

2 https://edificionado.wordpress.com/ 2012/11/10/6274-clive-oakland/, accessed 30 May 2019.

Chad Randl is Art DeMuro Assistant Professor in the Historic Preservation Program, College of Design, at the University of Oregon in Portland. Previously, he taught at Cornell University and worked as an architectural historian for the National Park Service. He is the author of Revolving Architecture: A History of Buildings that Rotate, Swivel, and Pivot.

(From A-frame Second Edition © 2020 Chad Randl, published by Princeton Architectural Press, reprinted with permission of the publisher.)