During the worst weeks of the coronavirus pandemic in New York City, demolition permits were filed for 15–19 Beekman Street, the site of a historically significant late 19th-century Classical Revival office tower designed by McKim, Mead & White that serves as a core contributing building to Lower Manhattan’s Fulton-Nassau Historic District, which was federally designated in 2005.

The April decision, which critics say was carried out with no community engagement, has roiled local residents, including members of Community Board 1, as well as architectural historians and preservationists citywide. A recent Change.org petition referred to the move as a “deeply disturbing way to proceed.”

Plans call for the 14-story tower and an adjacent corner building that’s part of the same property to be razed to make way for a 27-story mixed-use complex developed by SL Green Realty. The new building is set to be home to a new academic/residential hub for Pace University that includes dorms, classrooms, a dining hall, library, and more. Manish Chadha of Ismael Leyva Architects is listed on city permit filings as the project’s architect of record.

Marc Donnenfeld, a resident of the Fulton-Nassau Historic District and former CB1 member who is helping lead the community effort to save the building, told AN that he believes that SL Green and Pace University are “using the current crisis as cover in order to push it [the planned development] along.” He also doubts that the developer “even considered the possibility of reusing the building” and refers to the adaptive reuse of the historic structure as “a way to honor the past and look forward to the future.”

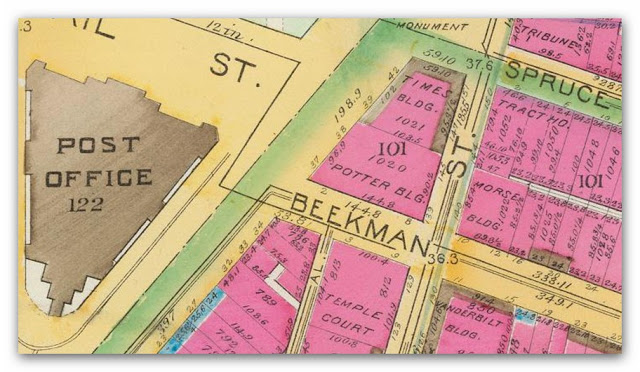

“The drawings that I’ve seen of the building that they’d like to construct are pretty shocking,” said Donnenfeld, noting the jarring contrast it would have against a trio of stately historic high-rises that stand tall on the corner of Beekman and Nassau Streets: The Queen Anne-style Temple Court Building (1883) and its annex at 5 Beekman, which were masterfully converted several years ago into the Beekman Hotel and Residences; the now-residential Potter Building (1886), an 11-story mishmash of styles at 35–38 Park Row/145 Nassau that Pace bought and attempted to demolish in the early 1970s, and the Morse Building (1880), a once-record-setting ten-story office tower, now a co-op building, on the northeast corner of Nassau and Beekman at 140 Nassau. All were built as commercial office buildings and later converted for other uses and all are city-protected landmarks.

“It has nothing to do with the contextual mores of the area at all—it’s just completely out there,” added Donnenfeld. “It obliterates a national treasure that’s been recognized by both the federal and state governments.” As noted in the petition, project plans sharing the 213,000 square foot development posted on the Pace University website have since been removed.

To that end, CB1 filed an emergency resolution in May with the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) in a last-ditch effort to save the building from imminent destruction by declaring it a historic landmark.

“The issue is that the city has not designated the district,” explained Donnenfeld. “It’s a state historic district and a federal historic district but it’s not a city historic district.” While federal and state landmark status comes with a high level of prestige (in this case well-deserved), it doesn’t impact private development. It’s a city-granted designation that could ultimately halt the wrecking ball.

According to Donnenfeld, Richard Guy Wilson, a noted architectural historian and professor at the University of Virginia, and Robert A.M Stern have both emailed the LPC in recent days to show their “support of landmarking the building, and supporting the idea of the city designating this district.” Mosette Broderick, a McKim, Mead & White scholar and director of the Urban Design and Architecture Studies Program and the Historical and Sustainable Architecture M.A. Program at New York University, has also endorsed city-bestowed landmark designation.

As of this writing, the NYC Department of Buildings database shows that a full demolition permit was processed on April 23 with no plan examination and is pending approval. A permit for non-structural interior demolition work submitted to the city that same day was approved in early May. Zoning approval to build the PACE dormitory and academic complex is pending.

“You don’t just throw away McKim, Mead & White buildings”

Completed in 1892, 15 Beekman is among New York City’s earliest proto-skyscrapers—technically an “early tall building”—and one of only a small handful of vertically oriented commercial structures designed by McKim, Mead & White while all three principals were alive.

“They didn’t really do tall buildings,” explained Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council. “They didn’t even really like tall buildings that much. So that this exists makes it worthy of serious consideration to begin with. You don’t just throw away McKim, Mead & White buildings.” (The New York City Department of Planning clearly didn’t get the memo in the early 1960s.)

“And you don’t throw away McKim, Mead & White buildings that are fairly rare examples of their work in a specific typography that was really characteristic of that area during the Gilded Age era,” Bankoff added.

Per a graphic from the Skyscraper Museum used in a Request for Evaluation document prepared for the LPC and shared with AN, a total of 21 Manhattan buildings with 10 or more floors were built in 1893. Only six, including the structure at 15 Beekman, remain. A squat four-story commercial building, constructed in 1924 to replace an older seven-story structure, sits adjacent to the endangered McKim, Mead & White tower on the corner of Nassau and Beekman. It too, as mentioned, will be demolished to make way for the Pace University building.

Matters of height aside, there’s also the slated-for-demolition tower’s name: The Vanderbilt.

Built from brick and terra-cotta by prominent New York builder Charles T. Wills, the classic tripartite tower is, not surprisingly, named after the men who financed it, Cornelius and William K. Vanderbilt, for a whopping $400,000. This price ensured that the office building would have all the state-of-the-art bells and whistles of the time: steam heating, fireproofing, a telephone system, and an Otis elevator.

The Vanderbilt was somewhat of an anomaly in the architect-client relationship between McKim, Mead & White and their ultra-wealthy New York family. Charles Follen McKim, William Rutherford Mead, and Stanford White, alongside Richard Morris Hunt, remain best known as the go-to architects for the Vanderbilt clan when they were in need of palatial country estates. Most notable is the Frederick Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park, New York, which was completed in 1899. In addition to their Vanderbilt commissions, the exhaustive list of completed works by the firm in and around New York City include the campus of Columbia University, the Brooklyn Museum, the Washington Square Arch, a smattering of private social clubs, and old Pennsylvania Station, a beloved but short-lived Beaux-Arts masterpiece that’s demolition kickstarted the modern-day city landmarking movement.

As a downtown office building, the Vanderbilt has lived a decidedly less visible or glamorous life than other works by McKim, Mead & White; it’s always been a workaday office tower. (For some time, the New York City Office of Naturalization was housed in the building.) Still, as stressed by Bankoff, the Vanderbilt’s quotidian function shouldn’t detract from its historic pedigree.

“This is one of these artifacts of its time, designed by arguably the finest architectural firm in American history—if you’re going to talk specifically about firms, it’s McKim, Mead & White and SOM that really changed the way America looks.”

And like Donnenfeld, Bankoff doesn’t come out against the potential redevelopment of the Vanderbilt. He does, however, argue that adaptive reuse, not demolition, is the only reasonable answer, especially when neighboring historic buildings have shown it can be done with aplomb.

“Preservation and adaptive reuse are actually sustainable and successful in that area,” said Bankoff. “The Vanderbilt is a 14-story building that is completely usable. There’s no need for that [demolishing a functional commercial structure and building anew] regardless of its historic importance and regardless of its aesthetic interest.”

AN will update this story according with any further developments.