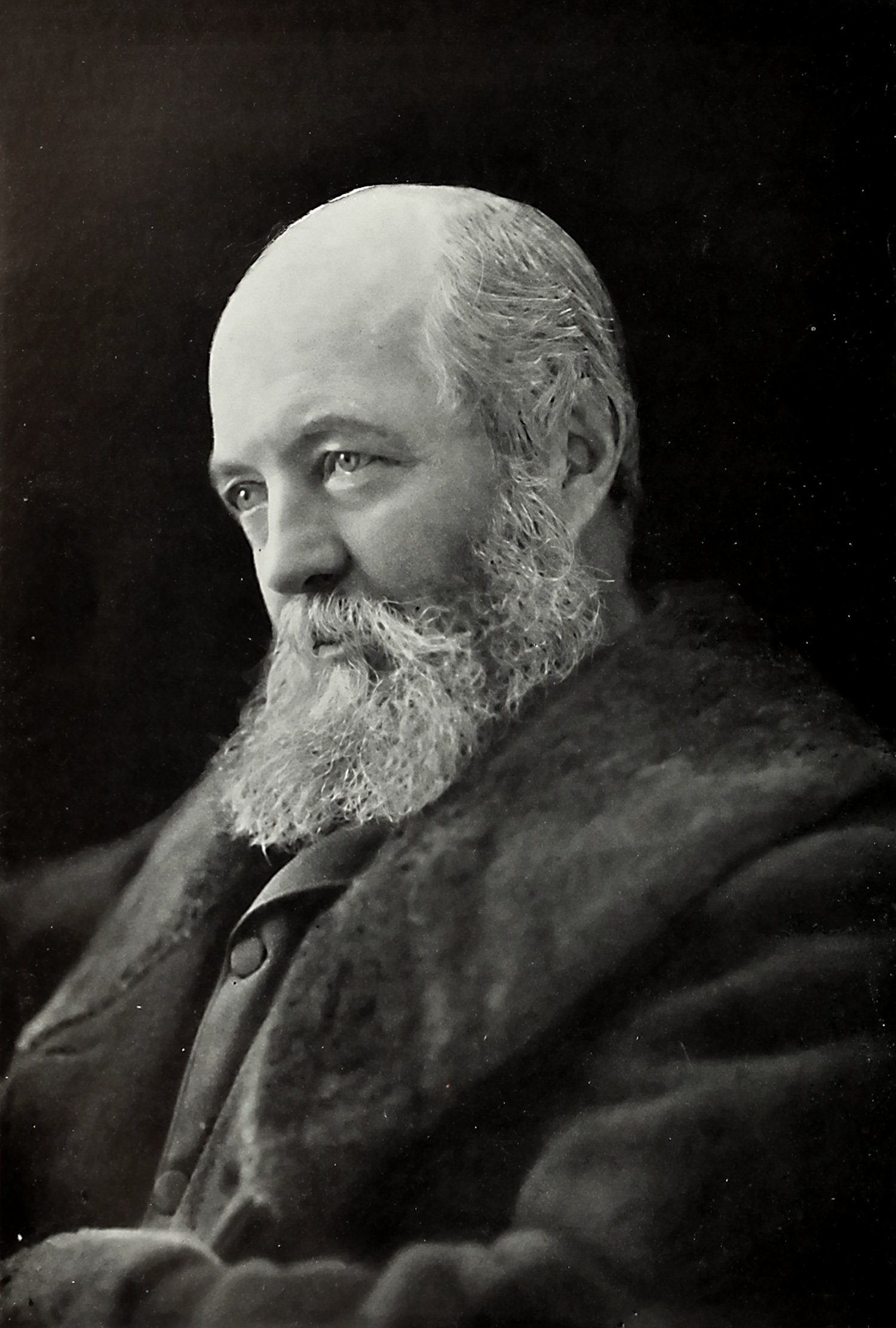

A 17th-century farmhouse on the South Shore of Staten Island once inhabited by pioneering American park-maker, landscape architect, and journalist Frederick Law Olmsted is one of 18 New York sites recommended for listing on both the State and National Register of Historic Places by the New York State Board for Historic Preservation. If approved for the latter, it would join over 12,000 different New York historic properties, including historic districts, listed on the NRHP.

Other sites recommended by the Board include the Mary E. Bell House, a historic house-museum centered around Long Island’s African American history in Suffolk County; the Lafayette Flats, a Classical Revival-style apartment building in Buffalo; and a hued-as-described Italianate villa known as the Pink House in Allegheny County. Of the 18 recommended sites, the Staten Island farmhouse where Olmsted lived from 1848 to 1855 is the only one located in New York City.

“These historic locations highlight so much of what is exceptional about New York and its incredible contributions to our nation’s history,” said New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in a statement. “By placing these landmarks on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, we are helping to ensure these places and their caretakers have the funding needed to preserve, improve, and promote the best of this great state.”

While the Connecticut-born Olmsted is best known for his completed works, most with Calvert Vaux, in other boroughs—namely Manhattan’s Central Park, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, and Forest Park in Queens among others—his associations with Staten Island are lesser-known, although he did design the popular Clove Lakes Park and a 22-acre burial plot for the Vanderbilt family there.

However short-lived Olmsted’s time spent living and farming on Staten Island at the 125-acre Tosomock Farm, previously known as the Ackerly Homestead, it played a formative role in the burgeoning career of the visionary landscape architect. He was in his mid-20s when he retreated to the pastoral confines of the New Jersey-adjacent island and transformed the existing farm into somewhat of an open-air horticultural laboratory, complete with experimental nursery and ornamental garden, for concepts and ideas that he would later employ in his park designs.

Among the various subsequent owners of the farm, which has been subdivided and redeveloped over the centuries, are Olmsted’s brother John Hull Olmsted, and Canadian journalist-turned-19th century Staten Island real estate developer Erastus Wiman. While the original property has dramatically shrunk to just 1.7 acres due to the suburbanization of Staten Island, the original house itself, originally just a single-room stone affair when built circa 1680, has been expanded significantly by various owners including Olmsted himself.

The remaining Flemish-style farmhouse, known as the Olmsted-Beil House, was declared a city landmark in 1967 by the Landmarks Preservation Commission (an early designation for the Commission as pointed out by 6sqft). It was acquired by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation in 2006 for $600,00 according to a 2019 article published in the Staten Island Advance detailing the ongoing efforts to save and restore the home. The “Beil” in Olmsted-Beil House, located in what’s now the Eltingville neighborhood, is the surname of the family that purchased the property in 1955 and owned it through 2006. Family patriarch Carlton Biel was a noted naturalist and curator at the Museum of Natural History.

Despite being part of a park operated by the NYC Park Department, the Olmsted-Beil House—“somewhat deteriorated” but apparently “structurally intact” per the State Board of Historic Preservation—is in serious need of restoration. As detailed in the NRHP registration form completed by the Board, the building “retains sufficient integrity from Olmsted’s period of residence to illustrate his significant association with the resource.”

“It is the most important and sole surviving building associated with this significant period in Olmsted’s life; it is substantially intact to the Olmsted period, and it would be clearly recognizable to him and his family,” added the report.

Per the report, five trees—two cedars of Lebanon, a gingko, a black walnut, and an Osage orange—found on the remaining property are believed to be have been planted by Olmsted and are the only surviving remnants of his early agrarian endeavors.

In 2018, the Friends of Olmsted-Beil House was formed with the mission to “protect, preserve, and present the site” for future generations. Being listed on the State and National Historic Registers would open up the site to eligibility for preservation programs like matching state grants and federal historic preservation tax credits. Earlier this year, the New York Landmarks Conservancy raised enough funds to complete much-needed stabilization work at the building, which it called a “forgotten and abandoned landmark in desperate need of attention.”

“This is where Frederick Law Olmsted took his baby steps in affecting a landscape,” said Felicity Beil, a board member of the Friends of Olmsted-Beil House and former resident of the home, in an informative video produced by the group, which hopes to eventually open up the home for educational tours.

Aside from Fairsted, the Brookline, Massachusetts, property where Olmsted established his landscape architecture practice in 1883 and lived until his death in 1903, the Staten Island farmhouse is believed to be the only surviving property owned and occupied by Olmsted himself according to the report. Fairsted was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and is now operated as a National Historic Site.

Once the Olmsted-Beil House and the 17 recommendations put forth by the board are approved by Commissioner of the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Erik Kulleseid, who serves as the State Historic Preservation Officer, and listed on the New York State Register of Historic Places, they can then be formally nominated for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.