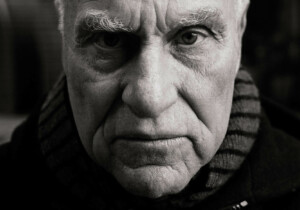

Architect and urban planner George Kostritsky, the last surviving ‘initial’ partner of the global design firm RTKL Associates, passed away July 30 in Maryland of complications from coronavirus. He was 98.

Kostritsky was the K in RTKL, now CallisonRTKL, a subsidiary of Arcadis NV. He joined founding partners Archibald Rogers, Francis Taliaferro, and Charles Lamb in 1961 to form Rogers, Taliaferro, Kostritsky and Lamb.

During his tenure with RTKL, Kostritsky was responsible for many of the pioneering urban design projects that RTKL led in the United States, starting with the 33-acre Charles Center urban renewal project in downtown Baltimore.

Besides outliving Rogers, Taliaferro and Lamb, Kostritsky was the last living planner or public official who was involved in the early years of Charles Center, which began more than 60 years ago.

“He was the last of that era in Baltimore,” said local architect Tom Gamper.

Kostritsky applied what he learned in Baltimore to urban revitalization projects in Albany, New York; Hartford, Connecticut; Eugene, Oregon; Cincinnati, Ohio, and Charlotte, North Carolina. In the process, he helped transform RTKL into an architectural and urban design firm that has helped rejuvenate cities around the world. RTKL was also one of the first American design firms to work in China. After merging with Callison in 2015 to form CallisonRTKL, its influence continued to grow.

“Urban planning is embedded in CallisonRTKL’s DNA,” said president and CEO Kelly Farrell. “Our deep understanding of urban environments began with George Kostritsky.”

Socially, Kostritsky and his wife Penny were friends with the writer and urbanist Jane Jacobs, and both are mentioned in Jacobs’ seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Kostritsky also worked abroad as an urban design consultant for the United Nations and taught at Harvard University and other institutions.

One of his best-known buildings is Charles Center South, an office tower at 36 S. Charles Street in Baltimore that he designed with Mario L. Schack. Known for paying attention to details as well as the big picture, he also designed, and even obtained U. S. patents for, the sugar cube-shaped streetlamps that still illuminate Charles Center’s public spaces.

According to a biography provided by CallisonRTKL, George Eugene Kostritsky was born in 1922 in Shanghai, where his Russian parents had settled after crossing Siberia to flee the Bolsheviks. When he was four his family moved to San Francisco, where he was raised and attended Polytechnic High School.

Fluent in Russian, he joined the U. S. Navy during World War II and served in North Carolina and Virginia as a Russian interpreter. He married the former Margaret “Penny” Long in 1943 and moved back to San Francisco after the war.

Kostritsky earned a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from the University of California at Berkeley and, after a year at Princeton University’s School of Architecture, a Master’s degree in Planning and Urban Design from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1952. His thesis at MIT, “The Neighborhood Concept: An Evaluation,” focused on designing urban areas not to solve physical problems but to meet social needs.

Kostritsky began his career at a time when many American cities needed rejuvenation and benefitted from designers willing to take a new approach to reviving them. His work in Baltimore brought him in contact with others who shared his passion for revitalizing cities, including planner David Wallace and developer James Rouse.

Kostritsky’s first job in architecture and planning was with Mayer & Whittlesey in New York. He moved to Baltimore in 1957 at the suggestion of Wallace, who was leading a team to redevelop downtown Baltimore for the recently formed Greater Baltimore Committee, led by Rouse.

According to Gamper and Tracy Schneider of CallisonRTKL, Kostritsky met his future RTKL partners, then practicing in Annapolis as Rogers, Taliaferro and Lamb, while working as the project director on the initial programming phase of Charles Center.

“The three architects were impressed by the methodology that George brought to the project as well as his approach in redesigning downtowns,” Schneider wrote in the company’s biography of Kostritsky. “In 1961, they asked George to join them as a partner.”

The firm was renamed RTKL and moved to Baltimore, where it became the master planner for Charles Center, designing the public spaces and laying the groundwork for new buildings. Among the architects selected to design individual structures in Charles Center were Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; John Johansen; Peterson & Brickbauer; Emery Roth & Sons; Conklin & Rossant, and RTKL.

Kostritsky, who led the Charles Center planning effort for RTKL, was a Modernist from the start and kept records of everything he designed going back to graduate school, said Gamper, an architect with Schamu, Machowski + Patterson (SM+P Architects) in Baltimore and longtime friend of Kostritsky.

Baltimore has a few diehard modern architects left, including Charles Brickbauer and Donald Sickler, both of whom worked with Mies. But in the field of urban planning, “he’s the last of that generation of truly heroic modernists” in Baltimore, Gamper said. “What we have to keep in mind is that a lot of the Baltimore-based firms evolved into Modernism. RTKL was born modern. Right out of the gate.”

He was also a supreme optimist, Gamper said.

“I think he left a real love for cities and their potential as human habitat, as built environment. He never lost his joyous optimism in anything he was doing. Even when he was a juror, he had fun with young high school kids. He just was fun to be around.”

Kostritsky brought a new way of thinking about urban planning, an approach that went beyond attempting to maximize profits from real estate, Farrell said in a phone interview.

Farrell added Kostritsky was certainly always conscious of working within a budget, but he also looked as planning as much more than a financial exercise. Kostritsky was also instrumental in instilling the firm’s “ethos of placemaking.”

“We truly believe that the experience people have drives the outcome, and if you focus on making a great place, if you focus on driving a beautiful experience, something that helps people, the rest of the mechanics are easy,” she said. “I think that ethos very much got infused into the firm with George.”

Charles Center was a large planning project when he first got involved, but Kostritsky also paid attention to details such as lampposts, Farrell said. “You can see his attention to detail, all the way down to figuring out what the light fixtures were. He brought a real sense of how to look at something quite large and oppressive and then create the finer details that help it all hold together.”

In 1968, under the auspices of RTKL, Kostritsky applied for and received two U. S. patents for the light fixtures he had designed for Charles Center, a modernist take on the traditional lamppost and globe. The design, calling for lights that are essentially illuminated sugar cubes, was later repeated around Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and at Fountain Square in Cincinnati.

“You see his influence throughout Baltimore. You see it when you go to Albany, if you find yourself in Hartford or in Charlotte. I think what you’ll find in those places, and especially in the re-urbanization of those places, you’ll find beautiful attention to detail in the main streets and the city squares. It’s the whole sequence, if you will, to how landscape plays a role, how people gather. He had an innate knowledge of how people gather in public spaces.”

Besides designing individual buildings such as arenas, she said, good designers today need to shape their surroundings, and that’s what Kostritsky advocated.

Kostritsky enjoyed working on smaller projects as well as overseeing large ventures, his daughter, Juliet Kostritsky, told CallisonRTKL for its biography.

“My dad was always sketching,” she said. “One day he went down into our basement and used his electric saw to build a wooden model of the Charles Center South office tower. When he came upstairs, he was so excited to show it to us…I remember like it was yesterday.”

Kostritsky was an AIA member in Maryland and the District of Columbia from 1963 to 1976. In the late 1970s, he left RTKL to become an urban design consultant for the United Nations in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and in Nigeria. He also taught at Harvard University, the University of Oregon, Howard University, and the Gilman School in Baltimore before retiring in 1995.

After the death in 1991 of his wife Penny, Kostritsky met a woman named Sheila Hoffman at a Father’s Day luncheon at the Engineer’s Club in Baltimore

The two became companions and shared a home together in the Linden Green section of Baltimore’s historic Bolton Hill neighborhood. They lived in one of the few parts of the neighborhood with contemporary homes. According to the Sun, they enjoyed gardening, and he painted with watercolors.

A few years ago, Kostritsky had to move to an assisted living facility for seniors, Brightview Towson. Gamper said that’s where he was when he was found to have contracted coronavirus, and he passed away shortly afterwards.

In addition to Hoffman and his daughter, a lawyer and law professor in Cleveland, Kostritsky is survived by his son Gyorgy in Timonium, Maryland; a son-in-law, Bradford Gellert of Cleveland, and a grandson, Christopher Gellert of Paris. No services were held because of the pandemic.

Farrell said that while it’s a great loss that Kostritsky passed away, it’s also an opportunity to recognize what he achieved.

“Planners are sometimes not celebrated, because it takes a lifetime for their work to come to fruition,” she said. “You do a master plan for 100 years, you’re probably not going to live to see it to its fullest. In a way, it’s a nice time to step back and celebrate all of those plans that have come to life with his influence.”