Scottish design curator Michelle Millar Fisher has made waves in the United States’ museum scene for the past 15 years. From roles at the Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the culture maker has imbued this sometimes-musty world with a sense of dynamism and exuberance.

Outside of these influential positions—in which she’s worked on such groundbreaking exhibitions as Designs for Different Futures from 2019 and Items: Is Fashion Modern? from 2017—Fisher has also spearheaded several format-defying curatorial initiatives of her own. An interest in addressing and exposing social inequities through the lens of design has led to such projects as the Art/Museum Salary Transparency 2019 spreadsheet. This open resource demystifies compensation at major art institutions and has sparked museum staff unionization drives throughout the country. Recent projects like the Designing Motherhood book and exhibition, developed with design thinker Amber Winick, derive from Fisher’s passion for exploring different narratives and perspectives within design history.

In her current position as the Ronald C. and Anita L. Wornick Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Fisher’s research focuses on different social histories and where architecture, museums, and art pedagogy intersect. She has lectured at Parsons School of Design, Baruch College, and Harvard Graduate School of Design. Fisher espouses the principles of transparency, access, collaboration, and critical thinking rather than outdated, insular definitions of design that center on aesthetics and style. Like her mentors Paola Antonelli and Juliet Kinchin, she is far more interested in exploring an expanded definition of the discipline.

AN contributor Adrian Madlener spoke to Fisher about her various endeavors and the state of design and curation in 2020.

The Architect’s Newspaper: From the COVID-19 pandemic to an economic recession, the Black Lives Matter protests, numerous natural disasters, and a dramatic election season, 2020 has been a momentous year. How do you think design has fared? How have some of your projects responded to these seismic events?

Michelle Millar Fisher: I don’t subscribe to the trope that COVID-19 was the straw that broke the camel’s back, but recognize that it exposed many fault lines, including the way capital works. Things were already in motion, but the pandemic allowed institutions to trim the fat and provide their employees with fewer resources. The empowerment and activism that has come to fruition this year stems back to the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013. The young people that came of age in the last ten years have been mobilized because of the racial and social injustice they’ve encountered. Concurrent to that, this generation, fully expecting to climb the professional ladder like their parents, were confronted by the 2008 economic recession. Designers in particular invested their blood, sweat, tears, and tons of money for overpriced design programs but are still struggling to get somewhere. It might have been the straw that broke the camel’s back in terms of the pandemic, but for the design and museum worlds, these challenges are nothing new.

COVID-19 has also revealed the power of collaboration. Too often credit goes to individual practitioners, but curators don’t work as individuals, nor do designers. The Art/Museum Salary Transparency spreadsheet project, itself a deeply collaborative project, began in May of 2019. Less than a year later, there were layoffs and furloughs for designers but also for the curators, manufacturers, and other professionals who work with them. It has therefore been important to see unionizations at many museums. It’s hard to say if this is a direct response to this year’s difficult circumstances, but they certainly have played a role. Over the last couple of months, there’s been an enormous expression of solidarity between art workers. Museum curators have also helped fundraise for initiatives like the Philadelphia Bail Fund. I think this sentiment is inherent to design and the principles that govern our field, the human resources we share, and how we treat each other as much as physical objects.

Talk about the Designing Motherhood project. How does this initiative reflect your interest in reevaluating design history and addressing social inequity?

I’ve worked in contemporary design for almost seven years now. At MoMA, I dealt with an extensive collection that covered a lot but also had many gaps. One area where this was most evident was in the lack of designs that address human reproduction. My argument at the time was that historic exhibitions like Alfred Barr and Philip Johnson’s Machine Art from 1934, which put technological innovations and mass production on a pedestal, failed to include equally influential industrially produced devices like the breast pump. The pump figured into the same design language of gadgets of a modernist design aesthetic and philosophy, but because of the interests of those who were making decisions at the time, it was entirely discounted. The conversation about the art of human reproduction was nonexistent, not just in terms of the notion of producing a child from one’s uterus but also contraception, other forms of reproductive agency, and health.

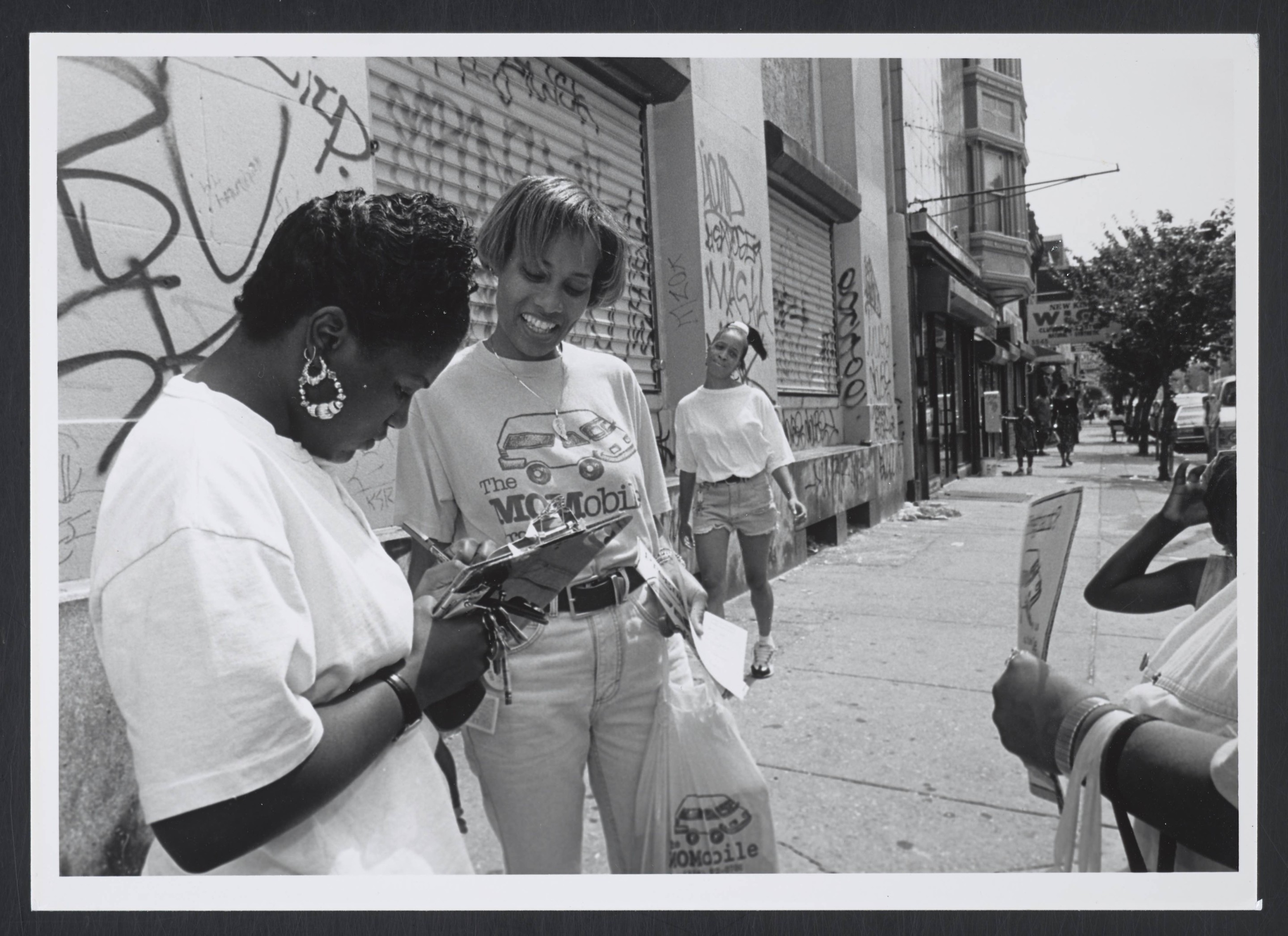

Developed with Amber Winick, Designing Motherhood came out of this realization, and we’ve been working on it for the better part of four years. MIT Press is currently publishing a book we co-authored on the topic. The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and the Center for Architecture+Design, Philadelphia, will mount a joint exhibition next year. Reproductive design touches every person and is not just a siloed women’s issue. No one on earth got here by any other means than being born. I am evangelical about this topic; it’s nearly impossible to find evidence of any relevant conversation in any design survey textbook on the topic. There wasn’t any broader discussion within design history about this ubiquitous issue until very recently.

Your interest in exploring expanded definitions of design, especially as the field pertains to social, political, and environmental issues, also informed your work on the Designs for Different Futures exhibition organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Walker Art Center last year. Can you talk more about the impetus behind this project and the idea of museums serving as a level playing field for the wider dissemination of information?

It used to be that design exhibitions were put up for visitors to marvel at new products without ever having to be critical about their wide-ranging implications or what the future might hold. For my cocurators in Chicago and Minneapolis and I, the aim of the Designs for Different Futures show was to explore the discipline’s role from a myriad of vantage points: labor, urbanism, food, the body, power structures, our planet, materials, and resources. The part I am proudest of shaping was ensuring a robust educational program. I went to the education department on my second day at the Philadelphia Museum of Art to codevelop programs with schools, families, and the general public that occupy a significant footprint in the exhibition space.

For me, this approach was a great experiment and something I will carry over to my next projects. We were able to think about how our audiences could engage with these thought-provoking objects and, as Paola Antonelli often says, have them consider how these designs are part of their lives. It’s something they shouldn’t be wary of but rather feel comfortable critiquing. It’s something they should be able to recognize and roll around on their tongues in ways that then allow them to make choices that are useful for them, and for people to become aware of how widely and how interconnected we are with our material worlds.