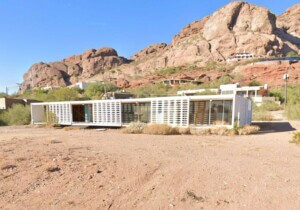

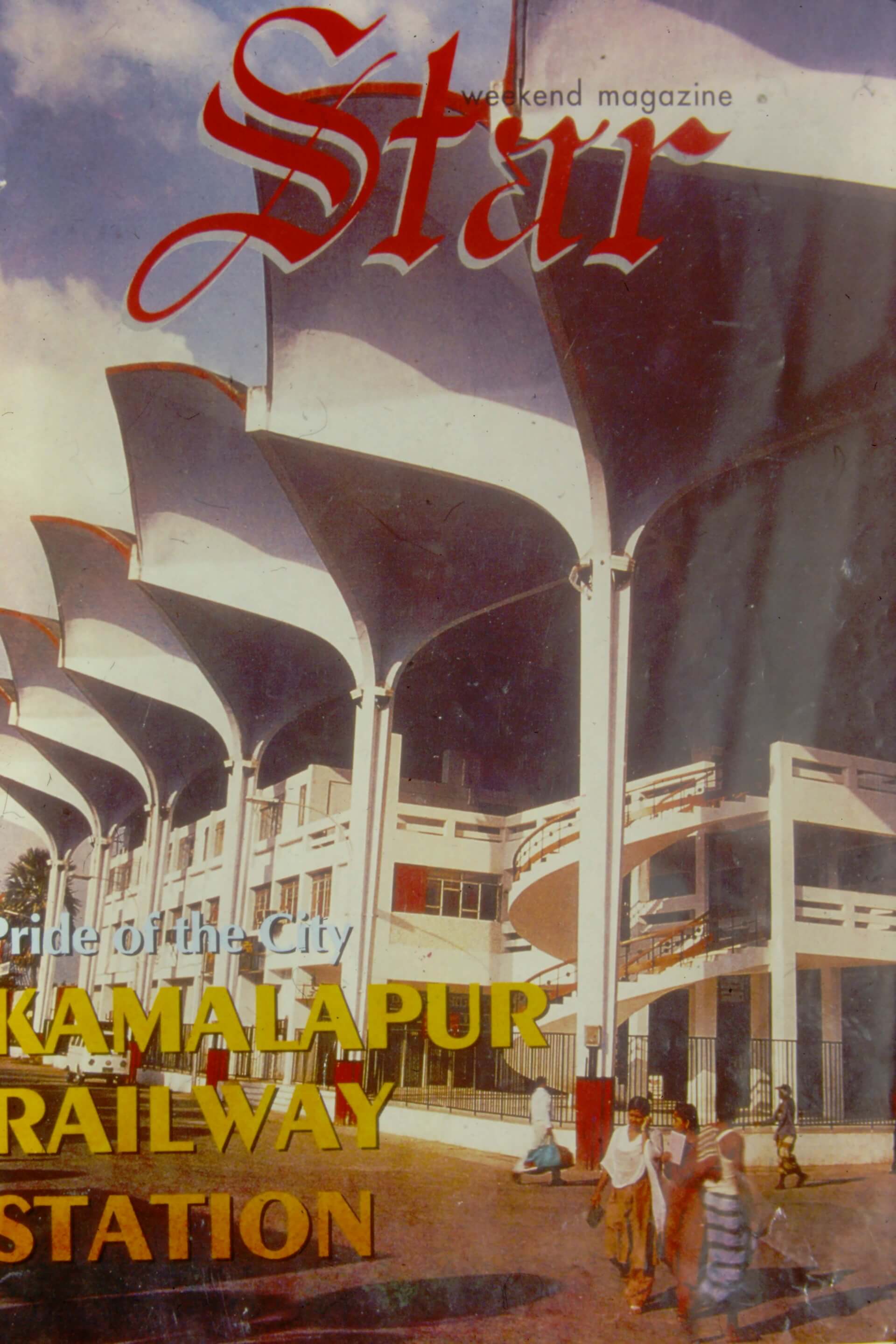

In central Dhaka, Bangladesh, a teeming megacity of 15 million people, a parabolic canopy rises above the skyline. The Kamalapur Railway Station has stood east of the city’s Motijheel district since 1968, when New Jersey-based Berger Consultants completed design and construction work on its thin concrete shell umbrella. It has since become something of a local icon, with many prominent Bangladeshi architects considering it an invaluable piece of cultural heritage. But with an expansion of Dhaka’s metro lines now imminent, Kamalapur is facing the threat of demolition.

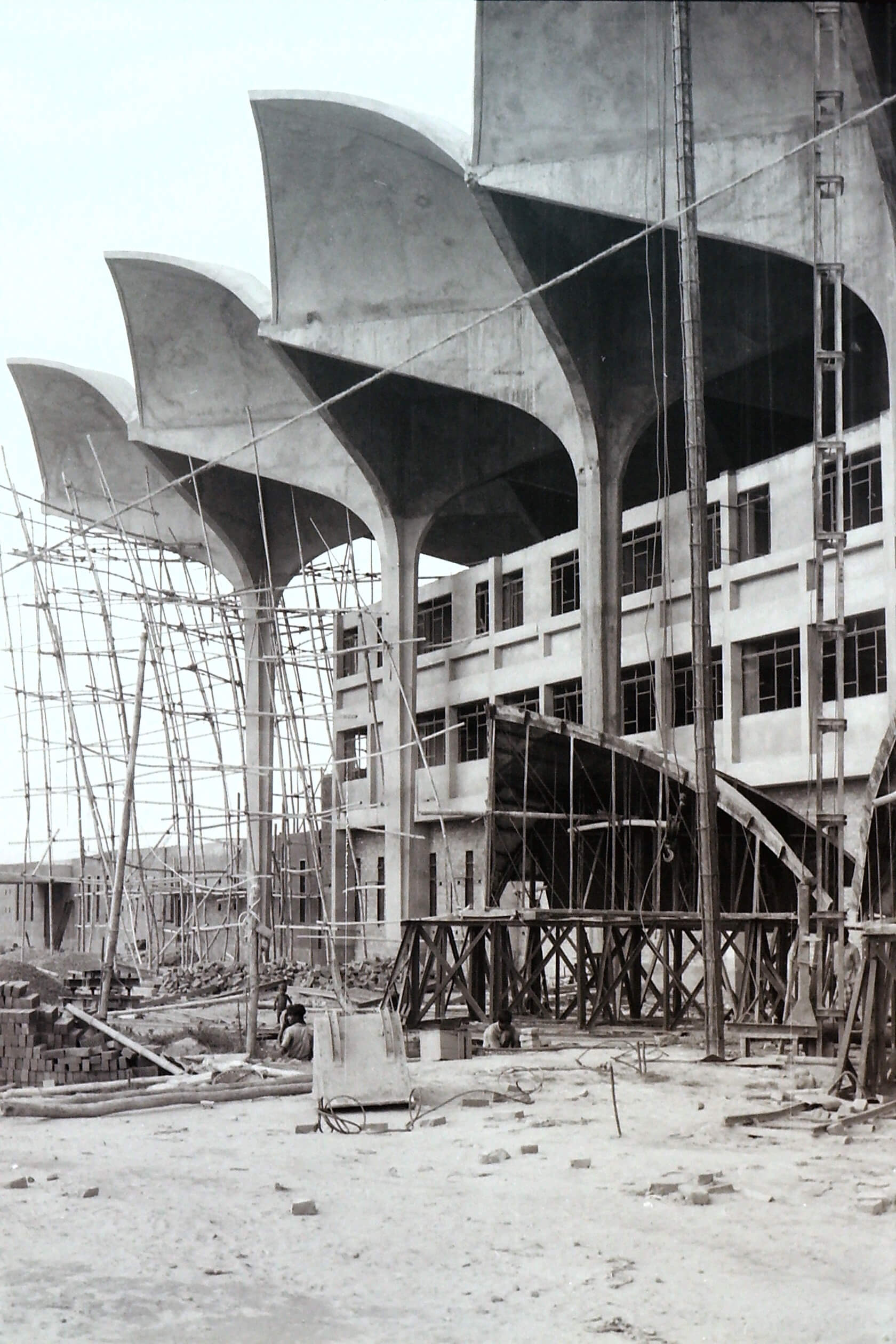

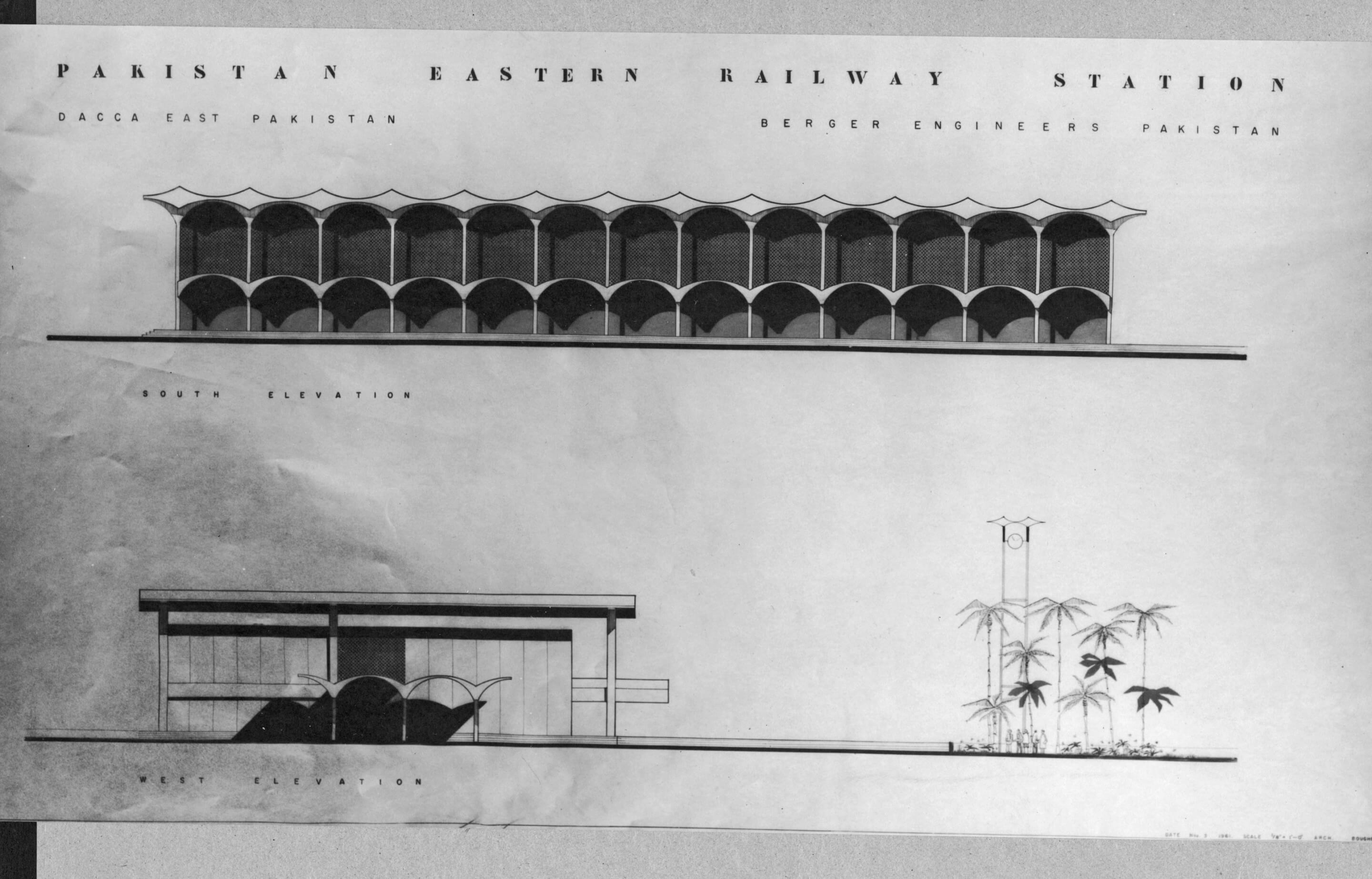

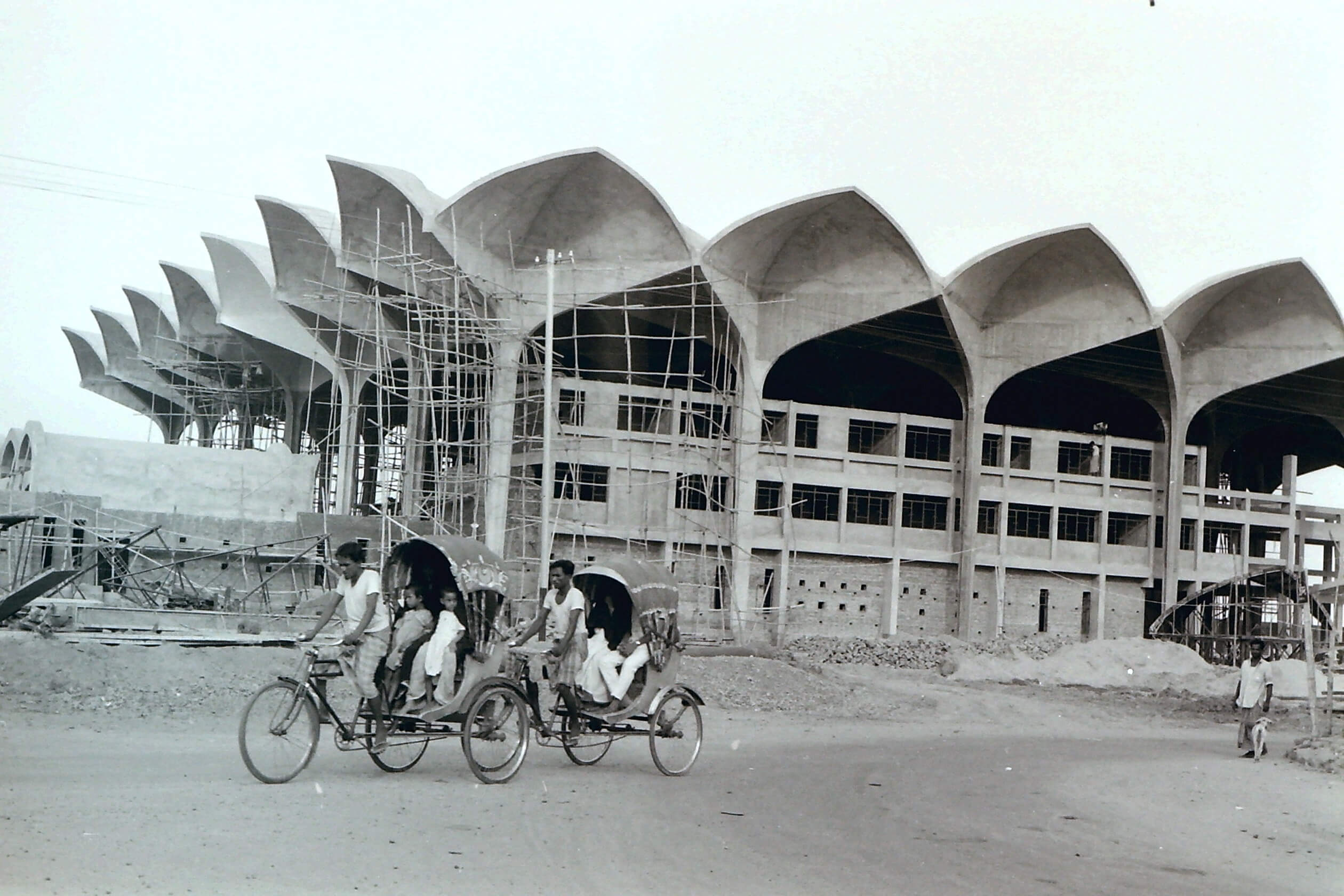

It took local craftsmen nearly a decade to build Kamalapur Railway Station, with a sequence of multiple architects at Berger Consultants developing its design. The first was Daniel Dunham, a young architect who had just completed his studies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) when Berger hired him to lead its fledgling Dhaka office and take on an extensive backlog of new projects.

Dunham enthusiastically embedded himself in Bangladeshi culture, learning Bengali and adapting to local craft and construction practices. Having researched tropical architecture as a Fulbright Scholar in Morocco, he expressed a deep interest in environmental design through his early architectural work.

Rather than design an enclosed monolith with mechanical heating and cooling systems for Dhaka’s central railway station, Dunham intended to take advantage of the city’s tropical climate. He devised a roof system that provides an umbrella of shade over the station’s offices and facilities, supported by a versatile field of columns. It was to be built using thin concrete shells, a construction technique that Dunham investigated as part of his thesis at the GSD. The open-air scheme takes advantage of Dhaka’s cross breezes while shielding interior spaces from monsoon downpours.

When Dunham left Berger to help lead the new architecture department at East Pakistan University of Engineering and Technology (now Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology), the Pratt-educated architect Robert Boughey took over his post. Boughey designed tessellating concrete shells for the roof that recalled the pointed arches of some Islamic architecture.

Cast on-site with reusable wooden molds, the shells became Kamalapur’s defining architectural feature. Adnan Morshed, an architectural historian at Catholic University, has likened them to the unmistakable rooflines of Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House.

Though it is not as globally recognizable as Australia’s most famous building, Kamalapur Railway Station has assumed its own prominent position in the architectural identity of Bangladesh’s capital. The reproduction of the station’s likeness is common in both local memorabilia and imitative design from other parts of the country. The Sylhet Railway Station in the northeastern part of the country, for instance, uses a similar umbrella structure to cover its facilities, with lotus-shaped shells supported by a forest of columns. In Dhaka, images of the city’s famous train station appear on postcards, stamps, and even decorative paintings on the backs of rickshaws.

Kamalapur is often framed as part of the so-called “golden age” of modern architecture in Bangladesh. Between the 1950s and 1960s, after the partition of India and before Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) claimed independence from Pakistan, a number of buildings erected in the country received international acclaim. Muzharul Islam designed his airy Institute of Arts and Crafts in Dhaka, as well as the Five Polytechnic Institutes in Rangpur, Bogra, Prana, Sylhet, and Barisal. Perhaps most famously, Louis Kahn began the decades-long process of designing what is arguably his magnum opus: Jatiya Sangsad Bhaban, or the National Parliament House of Bangladesh.

Even if Kamalapur Station is certainly not the only notable example of modern architecture in Bangladesh, though, it is likely one of the most accessible. While many of Islam and Kahn’s projects are located within lofty institutions of higher learning or high-security government compounds, Kamalapur’s open halls are traversed by thousands of ordinary Dhaka residents every day. With a patchwork of signage and posters now dotting the building’s discolored surfaces, Kamalapur has assumed a character that some consider inimitable—a notion that has only made the demolition announcement more difficult to accept.

In late November, Bangladeshi press outlets began reporting on the government’s plan to tear down Kamalapur Railway Station in order to accommodate an extension of the Dhaka Metro Rail’s Line-6, an elevated train route that aims to ferry upwards of 60,000 passengers per hour.

The Metro Rail is part of the country’s Strategic Transport Plan (STP), a scheme devised by the Dhaka Transport Coordination Authority (DCTA) to ease the city’s extreme levels of road congestion. For a metropolis that is growing faster than almost any other Asian city, mass transit projects could provide critical relief for an already inundated transport infrastructure system.

Plans put forth by the Japanese construction firm Kajima Corporation have already been approved by Railways Minister Nurul Islam Sujan, and the demolition will purportedly allow the DCTA to use Kamalapur as an effective multimodal hub for several new and existing train lines, though no site drawings have been released. According to New Age Bangladesh, Islam has promised that an exact replica of the existing structure will be built just to the north of its current site.

Many local and international architects, though, have criticized the decision as an unnecessary act of destruction, reflecting misplaced priorities and insufficient coordination between agencies. While hardly anyone disputes the need for new and improved rail infrastructure, prominent figures like Qazi Azizul Mowla, professor of urban design at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, suggest that the DCTA’s goals could be achieved without demolishing Kamalapur Railway Station.

As the Daily Star recently reported, Iqbal Habib, an architect and joint secretary of the nonprofit Bangladesh Paribesh Andolon, identified Kamalapur as one of Dhaka’s few examples of symbolic architecture. In a recent piece for the same publication, ABM Nurul Islam warned that the municipal government would later regret its seemingly insatiable appetite for new development: “Dhaka, once known as a city of mosques or the Venice of the east, will soon become a city of shopping malls—a shapeless concrete jungle if the current trends continue.”

Others have focused on the potential for adaptive reuse rather than demolition. In a conversation with AN, Kate Dunham, daughter of architect Daniel Dunham and an adjunct associate professor at Columbia GSAPP, emphasized Kamalapur’s versatility: “If it doesn’t work as a train station, that’s fine! But the whole principle of the building was that it was flexible, so I can’t imagine that it couldn’t house something else.”

In another article written for the Daily Star, Adnan Morshed drew parallels between the plan to destroy Kamalapur Railway Station and the infamous dismantling of New York City’s once grandiose Pennsylvania Station. The destruction of McKim, Mead, & White’s Beaux Arts masterpiece in 1963, deemed by many an unnecessary and tragic loss, sparked the modern historic preservation movement in the United States. Indeed, New York’s unveiling of the new Moynihan Train Hall last week has renewed interest in the global effort to preserve iconic public buildings as living vestiges of a place’s unique history.

Dhaka has no formal equivalent of New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, a public agency that recognizes and protects historically or architecturally significant buildings. The preservation efforts that do exist in the Bangladeshi capital often focus on Puran (Old) Dhaka, where merchants’ mansions, palaces, and churches from Britain’s colonial occupation line the Buriganga River.

The apparent apathy of Dhaka authorities towards the importance of leaving Kamalapur in its original form is reflective of broader trends across South Asia, where municipal and national governments are typically slow to steward modernist, post-independence buildings as critical components of a nation’s cultural heritage. In New Delhi, India, where the Heritage Conservation Committee does not protect structures younger than 60 years old, authorities disregarded international outcry and demolished Raj Rewal’s iconic Hall of Nations in 2017.

However, more recent signs show that increased global recognition of the richness of South Asia’s modern architectural history might have some impact on high-level decision-making. In 2018, Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi won the Pritzker Prize and was celebrated in an expansive retrospective at Germany’s Vitra Design Museum the following year. The Museum of Modern Art has acquired works by Rewal, and Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa has been the subject of gallery exhibitions in New York and Rome. Just last week, the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad caved to domestic and international pressure to withdraw its plans to demolish 18 of Louis Kahn’s dormitory buildings at the school.

With the final decision regarding the fate of Kamalapur Railway Station now in the hands of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, architects are hoping that similar pressure might prompt a reversal of the demolition plan. As for the station’s original architect, Kate Dunham assured AN that her late father was cognizant of both the importance of the project within Dhaka’s architectural landscape and the inherent volatility of doing work in a fast-growing country: “He was very humble, and would probably be more amused by the present situation than anything. He saw the humor and the value in things, and he certainly wouldn’t be egotistical about it.”