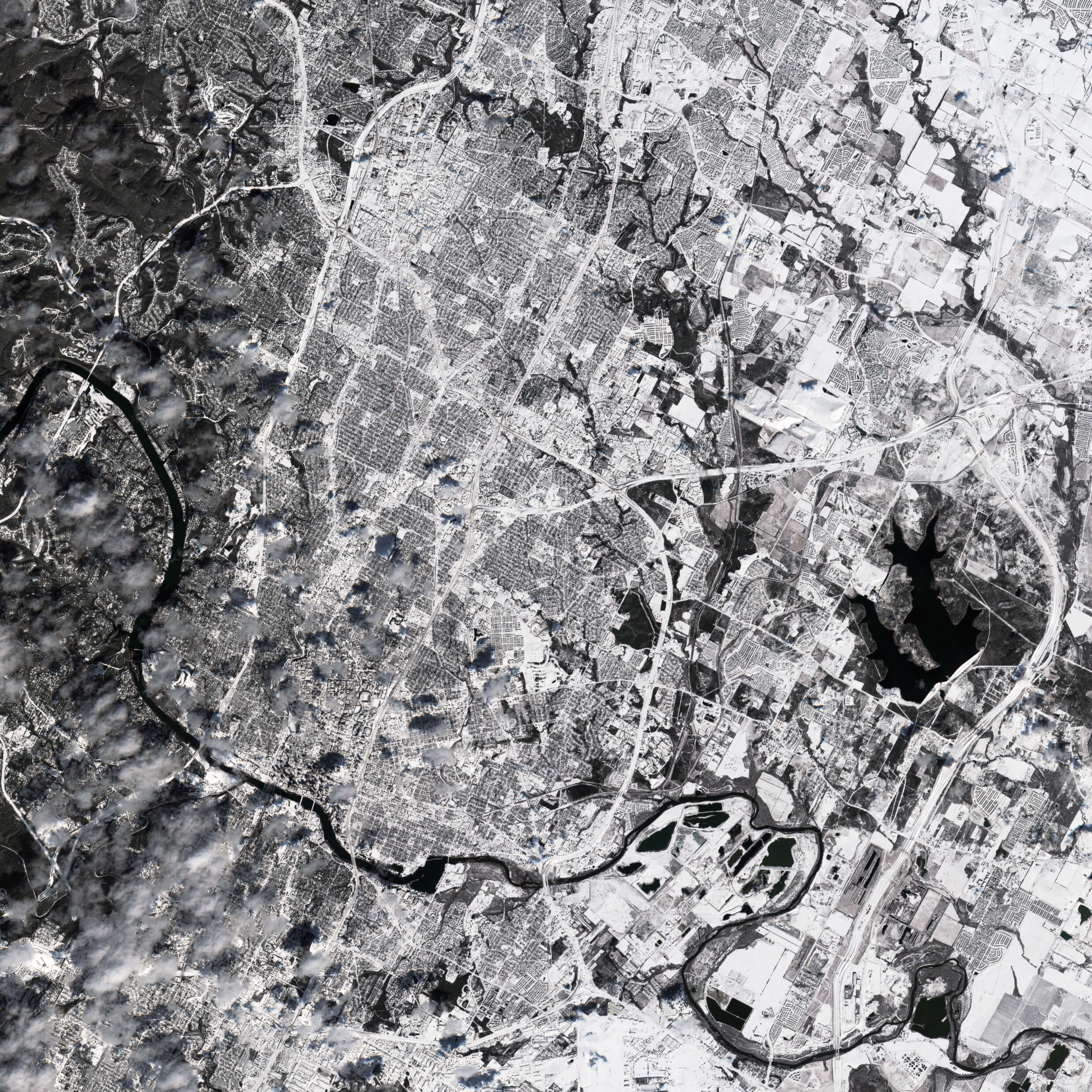

On Monday morning, residents across Texas awoke to a winter wonderland. Like many, I ventured outside to find my Houston neighborhood blanketed under an abstracting layer of snow.

It was a rare, calm sight, one that belied the nightmare many had already begun to endure. The night before, historically cold temperatures prompted a surge in energy consumption, leading to major failures in electricity generation and unplanned outages. The Electricity Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)—before this week an obscure state entity and today a widely despised one—directed suppliers to “shed load” (turn off peoples’ electricity) to avoid catastrophic failures. Millions of Texans lost power, and many are still without it. ERCOT now says the grid came within “seconds and minutes” of a catastrophe that would’ve left the state cold and dark for months.

Power loss also affects water sanitation systems, so many cities remain under a boil notice indefinitely. Hospitals in Austin are running out of water and are forced to transfer patients to nearby facilities with capacity. As of Thursday, nearly 12 million Texans face water disruptions. For the past three days, local officials have encouraged energy and water conservation to distribute limited resources more widely.

Just like the burst pipes flooding Texas houses, dystopian scenes quickly saturated the internet. With most of the city without power, downtown Houston, illuminated on Monday night, went dark on Tuesday after complaints from social media users pointing out the waste. While some in Austin snowboarded down its hills, others formed long lines outside grocery stores for supplies. A Houston man scoured his neighborhood for firewood to keep his family warm. Four died in a Sugar Land house fire after a family used a fireplace for heat, and Harris County has reported 580 cases of carbon monoxide poisoning, with two deaths. On South Padre Island, frigid sea turtles were rescued by the thousands and held at a nearby convention center. It was as if the bleak, near-future urban Texas of Christopher Brown’s recent sci-fi novel Rule of Capture had been brought to life and captured on Instagram Stories.

Still, there was local assistance when larger systems became unreliable. Calls for donations to mutual aid groups proliferated, and CrowdSource Rescue, which formed in Houston as a response to hurricane crises, activated for the freeze. Neighbors helped neighbors, meals were donated by the thousands, and first responders did their best to keep up.

All the while, state leadership was missing. Ted Cruz attempted to flee to Cancún, and Governor Greg Abbott was quick to blame the failure on wind turbines that normally provide Texas with 23 percent of its power, more than any state. But in reality, the culprits of the disaster are the coal and natural gas energy producers that hadn’t properly winterized their facilities after a spell of cold weather in 2011 had demonstrated the need for doing so. Energy prices spiked overnight on Sunday, and an ERCOT change on Monday allowed energy companies to bill customers at these high rates—a sign that the agency values the bottom line of companies over the bank accounts of Texans who are already suffering economically due to the pandemic. As many have noted, the current freeze has disproportionately affected low-income, nonwhite communities, the very same groups hardest hit by COVID-19.

What does this crisis mean for architecture? The impact is being most keenly felt at the residential scale. Some folks live in older pre-war homes that are uninsulated or thermally leaky, others live in newer multi-family buildings that were poorly built, and millions more inhabit suburban houses that are past their life expectancy. This disaster is bound to change design parameters. At larger scales, infrastructural maintenance will become even more important. If we can’t keep pipes and pipelines from freezing, then there is little hope for implementing smarter technological solutions. As areas thaw, residents will begin to make expensive repairs: an early estimate from the Insurance Council of Texas indicates it will be the costliest weather event in Texas history, more than Hurricane Harvey’s $19 billion in damages in 2017.

Weatherizing existing buildings to reduce energy use and constructing new energy-efficient buildings help combat climate change is necessary. There are already national provisions for this in the Congressional Action Plan for solving the climate crisis, and Texas’s four largest cities—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin—have passed Climate Action Plans that utilize improvements in the energy efficiency of buildings to meet their goals. But these efforts will inevitably be hampered by a state government that refuses to acknowledge the science: in its last session, the Texas legislature completely evaded the issue of climate change. Perhaps there is one hidden benefit of a winter storm that affected all of Texas’s 254 counties; rather than a hurricane whose destruction is limited to the Gulf Coast, the widespread damage brought on by the freeze might motivate consensus that big changes are needed.

Even the experience of living in the most high-performing passive house quickly becomes glamping without the electricity to heat it or water flowing from its taps. It’s of paramount importance to understand this crisis as not one of buildings or even technologies, but of governance. Texas’s state leaders—who retain control thanks to host of dirty tricks, from gerrymandering to voter suppression—continue to prioritize the interests of companies (largely the oil and gas industry) over provisions that would improve living conditions for Texans and prepare for an uncertain future. An attitude of rugged individualism, a fever dream leftover from frontier days, persists despite all the evidence of its ruinous effects. This may not be the future Republicans want, but it’s the future their policies have created.

Six months ago, hot and humid Houston narrowly avoided Hurricane Laura and is now shut down thanks to cold weather. The descent of the polar vortex across the country is one effect of climate change, but so is the corresponding institutional chaos. “The collapse of ERCOT is one of the many signs that Texas has failed, and continues to fail, to adapt its infrastructure to meet the inevitability of climate change,” Houston author Bryan Washington wrote in The New Yorker on Thursday. And time is of the essence—hurricane season begins in 102 days.

This is how systems fall apart—not from singular implosions but from neglecting decades of overdue maintenance. One expert predicts that a direct hit from a hurricane to the Port of Houston would be “‘America’s Chernobyl,’” at once devasting domestic energy production and spreading toxic sludge throughout Galveston Bay. “Build the Ike Dike” intones Houston pundit Evan Mintz, whose request continues to fall on deaf ears. Solutions exist—Rogers Partners has devised a separate mid-bay strategy for Houston—but they’re big, expensive, and require coordination. Who better to imagine new civic visions and lead the interdisciplinary teams that realize them than architects?

This freeze and other climate-related crises make plain the need for the architectural discipline to change its priorities. If architects want to be of their time, they must be meaningful participants in the struggles of their time. As James Baldwin wrote—and as Dallas Morning News architecture critic Mark Lamster echoed in his own assessment of the blizzard’s fallout—“not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

It should be noted that the current system works just fine for the elite it was designed to serve; it’s why Governor Abbott blames ideas like the Green New Deal instead of accepting responsibility for governmental negligence. This perversity is why systemic change is desperately needed to overcome what some in architecture have come to theorize as “carbon form,” whereby cheap energy drives architectural production. Academizing this condition doesn’t make it any easier to overcome, however. To crib from smarter thinkers, it’s “easier to imagine the end of Texas than an end to capitalism.”

Architecture can be boiled down to the act of organizing bodies and objects in space, and it is the organization of society that demands attention today. This is where architectural imagination should be directed going forward.

As I write on Thursday afternoon, the sun has come out in Houston, but emergency sirens fill the air. Response efforts have only just begun. Texas’s cities look the way they do because of cheap energy, and it was cheap energy that failed Texans this week. How we fix it is an “architectural problem,” sure, but more accurately it is a problem for our state—and, in a broad sense, America.

Jack Murphy is editor of Cite.