At first blush, High Island, Texas, sounds downright dystopian. A site of 20th-century oil extraction, the landscape has as its defining feature a massive salt dome—a pimple-like swell rising 38 feet above sea level. Located on the eastern side of Galveston Bay, just inland from the Gulf of Mexico, High Island is prone to destructive hurricanes and also has the dubious distinction of being a burial ground for the serial killer Dean Corll.

But for some, High Island is a haven: each spring, the site welcomes thousands of migratory birds on their northward journey from Mexico that are drawn to the freshwater reservoirs and local flora. Ten thousand birders flock to High Island’s bird sanctuaries annually, including Smith Oaks, a 177-acre site operated by the Houston Audubon Society. Now that site is better equipped to welcome them, thanks to the introduction of a 700-foot-long canopy walkway and support facilities from architects SWA Group and SCHAUM/SHIEH.

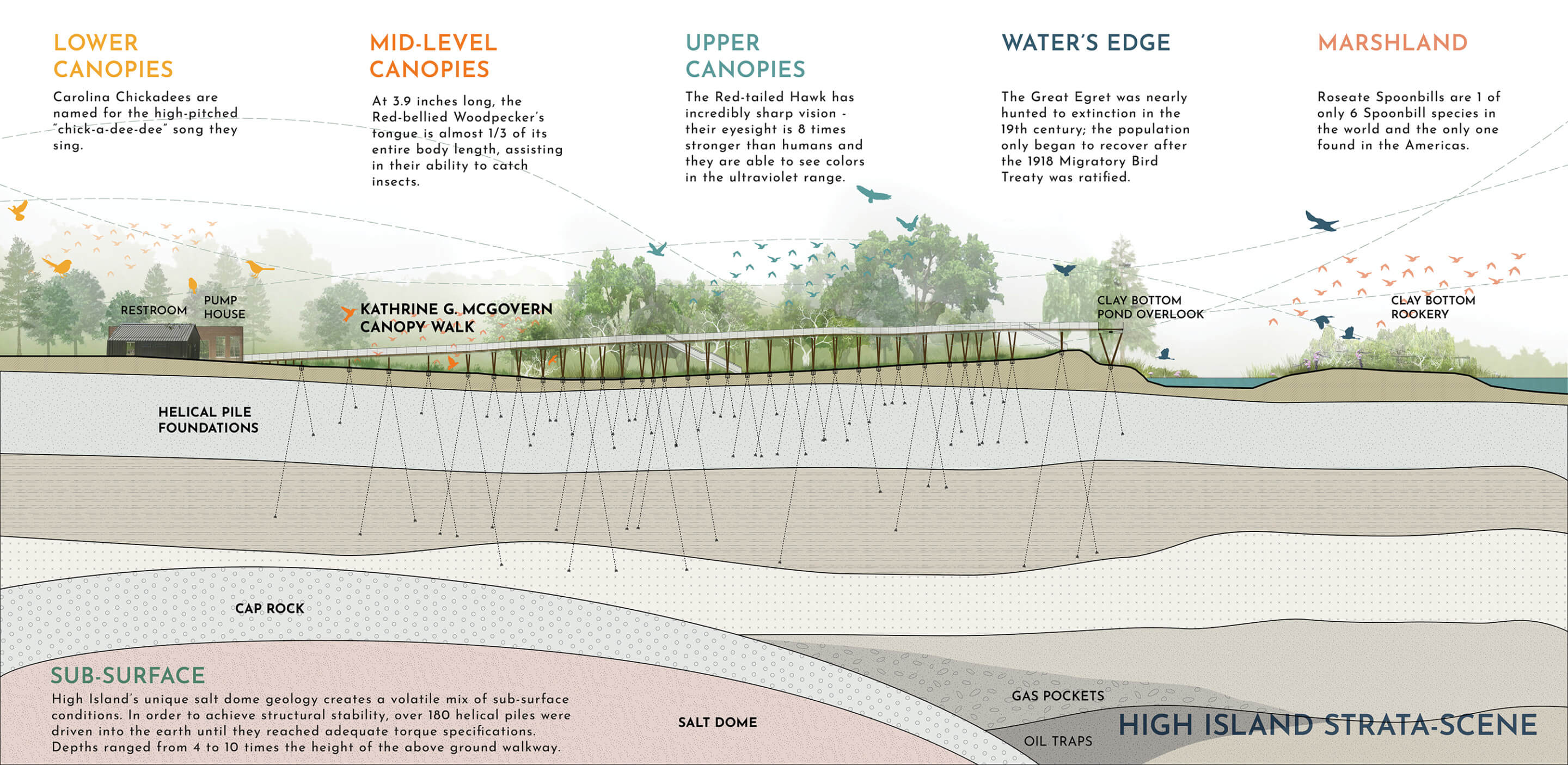

SWA, which Houston Audubon has engaged in a larger master-planning initiative for the High Island site, sees the interventions as a means of making the landscape and fauna accessible to a larger population. The Kathrine G. McGovern Canopy Walkway opened in the late spring of 2020, providing an outdoor escape for Houstonians an hour and a half up the road. Matt Baumgarten, an associate principal in SWA’s Houston office and design lead on the project, pointed out that the new elevated path immerses visitors in the landscape in a new way, “getting people up in the trees” and carving out “visual and educational accessibility that wasn’t here before.” (He and his children have frequented the site since the project’s opening last year.)

Building in a bird sanctuary is a sensitive endeavor. Nesting seasons had to be factored into construction timelines, and the walkway needed to seamlessly integrate into the surroundings so as not to disturb bird populations. To accomplish that, the designers embraced visual and acoustic forms of camouflage and a V-shaped base that was minimally invasive. The designers eschewed noisy metal decking in favor of kiln-dried southern yellow pine, a readily available material, so that the decking could be repaired easily as needed. “You can’t necessarily make something that’s going to last 500 years, but we did need the walkway to take high wind loads and copious rainfall,” said Baumgarten. Natalia Beard, principal in charge of the project at SWA, said that Smith Oaks’ industrial remnants were also taken as cues for the detailing of the underside. “It looks like this structure has always been here,” she said.

Elsewhere at Smith Oaks, the Houston- and New York City–based firm SCHAUM/SHIEH has completed two structures to support bird-peeping visitors. A 1920s brick pump house left over from the site’s oil-extracting years has been renewed and transformed into a flexible open-air pavilion. Adjacent to it, the designers have built a new concrete structure containing restrooms, water fountains, and an information kiosk. Whereas SWA’s walkway was intended to blend into the landscape, however, this structure needed to suggest arrival, explained Troy Schaum, co-principal at the studio: “Even if you’re one person down there—which often you might be—you would feel welcome, and it would be a marker that this is it, visually.” Accordingly, Schaum and his studio have appointed the structure with a steep gabled metal roof and a flat graphic facade painted Audubon green. The building’s asymmetrical composition was inspired by the wind-bent local trees, said Schaum.

In all areas, the avian populations came before anything else: if there was any evidence of disruption to a habitat during build-out, for example, construction had to cease. (Schaum said that there was even concern about the noise of the door closers on the bathroom potentially startling birds.) In activity and form, the goal was to intervene as little as possible: “It’s easier in architecture to imagine a solution that’s built, or that’s an action,” said Schaum. “It’s very hard to imagine a solution born out of restraint.