Where did it all go wrong? Liverpool, a city steeped in almost too much history, too much to begin to even list here, has somehow been stricken of its lofty status as being a UNESCO World Heritage Site following a UN vote in China yesterday.

Officially, it all went wrong after the city gave planning permission for a spate of new buildings, including a $685 Million stadium for Everton FC on the waterfront. This, according to the UN, resulted in a “serious deterioration” of the area. But in reality, the city’s downfall has been 12 years in the making.

It started in 2009 with a ferry terminal, a building so bad it won the Carbuncle Cup, ridiculed by judges at the time as “a shining example of bad architecture and bad planning.” Belfast-based Hamilton Architects were the unfortunate Carbuncle winners that year, attempting, in vain, to inject some Zaha-esque pizzazz onto the banks of the River Mersey. It didn’t go well. Zaha Hadid Architects later showed how they would actually accomplish the feat with the Havenhuis Antwerpen (Antwerp Port Authority Building) in Belgium, a controversial structure to some, but one which deals with heritage and dazzles many. ZHA entered that competition in 2009, most likely with lessons from Liverpool in mind, and the project was completed seven years later.

By then, Liverpool had gained another scar: the Museum of Liverpool. Designed by Danish practice 3XN and finished in 2011, this, bizarrely, was an even more grandiose attempt at a totalizing piece of architecture intent on leaving a misguided stamp of ‘modern architecture’ on the site. The museum in many ways attempted what the Ferry Terminal tried to do stylistically, but on a much larger scale. As a result, it failed even more spectacularly, albeit escaping the dreaded Carbuncle crown. “How could so many positive words – ‘regeneration’, ‘vision’, ‘culture’ – plus so much public and private funding, plus so much scrutiny by bodies such as the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, have led to what now stands on Liverpool’s waterfront?” opined The Observer’s Rowan Moore in a review.

At this stage, the city seemed disastrously hell-bent on architectural modernization. The UN fired a warning shot in 2012 in the wake of the Liverpool Waters development, which proposed a cluster of skyscrapers along the river. The UN deduced that the proposals would “irreversibly damage” the waterfront and result in a “serious loss of historical authenticity, and an important loss of cultural significance.”

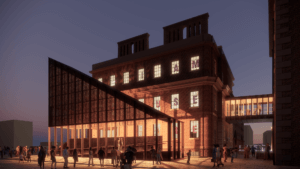

Come 2017, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) had weighed in… with its own building. ‘RIBA North’ is the institution’s main outpost outside of London, and Broadway Malyan’s design echoes the two aforementioned buildings’ balky riverside stance. Together, the trio create an uncomfortable ensemble of awkward angles; three buildings horribly out of sync, desperately trying some form of contemporary architectural dance along the water.

And so onto the Everton FC stadium, perhaps the final nail in the coffin. According to the UN, the project at Bramley-Moore dock would “add to the ascertained threat of further deterioration and loss” of the site’s historic value. The UN’s decision also comes after authorities ignored the red flags of 2012. A year after that warning, Liverpool gave the Liverpool Waters scheme the green light, with then-mayor Joe Anderson describing it as “fantastic news for Liverpool.”

To be clear, this is an embarrassment for Liverpool. The city joins only Oman’s Arabian Oryx Sanctuary and the Dresden Elbe valley in Germany as places struck off the list of World Heritage Sites in the last half-century. Each was delisted in 2007 and 2009, respectively. For a mere 17 years, Liverpool rubbed shoulders alongside the Taj Mahal and Great Wall of China. Many “World Heritage Site” signs will have to be taken down.

Current ‘metro mayor’ of the Liverpool city region, Steve Rotheram, told The Guardian that the UN’s decision was a “retrograde step that does not reflect the reality of what is happening on the ground” and was “a decision taken on the other side of the world by people who do not appear to understand the renaissance that has taken place in recent years.” Rotheram added that cities should not have to choose between maintaining heritage status or regeneration and bringing in jobs.

The World Monuments Fund (WMF) also commented on the matter. Speaking to AN, the WMF said it:

“regrets the removal of Liverpool as a World Heritage Site (WHS). This important historic city has a rich mercantile heritage and tells stories which are relevant to a global audience. Liverpool is also a special place for WMF, with the conservation of St. George’s Hall within the former WHS area being our first project in the UK. In light of UNESCO’s decision, we urge the UK government and city authorities to do more to protect Liverpool’s extraordinary heritage. We recognize that cities are dynamic, living places, always changing and never static. But we also champion development that enhances the historic character of place—creativity has always been part of Liverpool’s architectural, industrial, and cultural DNA. We hope the local decision-makers can bring new creativity to bear to ensure Liverpool’s past is protected.”