Even for multi-block, city-defining developments, blueprints often merely represent best-laid plans. The reams of traditional visuals and data used to describe bold real estate projects—square footage, cost, economic impact, and assorted dimensions and proportions—don’t really communicate the true impact such projects can have on neighborhoods and cities, leaving an incomplete picture when such proposals are evaluated.

That’s why a new breed of data-focused tools and toolkits wants to change how development is measured, to reshape what’s ultimately built. With new ways to track and evaluate social and sustainable impacts, designers, planners, and architects can bring more rigor, and ultimately achieve better results, with urban design.

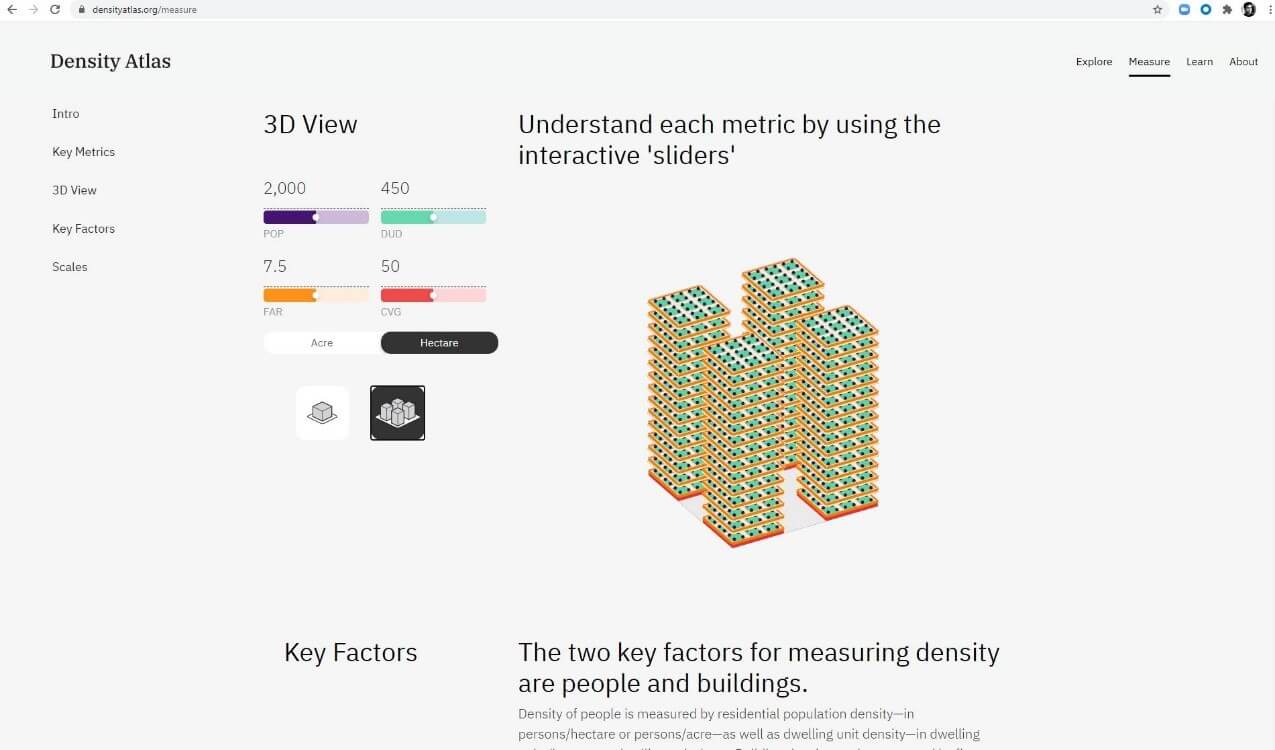

“Bringing the qualitative and quantitative together is where a lot of urban design resides,” said Mary Anne Ocampo, a principal and urban designer at Sasaki, the interdisciplinary design and architecture firm. The practice just launched an updated Density Atlas, a collection of diverse urban case studies measuring population density, building size, and floor area ratio, among other characteristics, to help planners, architects, and developers better understand how different facets of density affect design and cost. Sasaki inherited the project from famed MIT urbanism professor Tunney Lee, who passed away last year, and relaunched it this past spring.

“The intersection of financial investment, climate change responsibility, and equitable and just cities is very key,” Ocampo said. “The Density Atlas provides tools to help quantify these components.”

Breaking down preconceptions of what density means into standard measurements at the same scale, the Atlas aims to create a common language around the impact of how buildings are arranged. While planners tend to look at population density to determine the need for certain city services, realtors and developers may focus on dwelling unit density to understand sellable or rentable square feet. This global directory of different urban neighborhoods, which covers the block, neighborhood, and city scale, help different practitioners understand how planning and massing can affect a design project.

“It doesn’t solve everything, but metrics can be useful to compare different aspects of new communities,” Ocampo said.

Ocampo added that density lends itself to this kind of tool because without a common understanding of exactly what one is talking about, the term can be misleading. Combining different measurement tools, such as floor area ratio and neighborhood scale, allows for more common denominators, an especially important element when presenting projects to community groups and local leaders, who often prioritize neighborhood character and preservation and fear the impacts of increased capacity and population. Sasaki has just begun to use the tool in its own planning processes and hopes it will help the firm arrive at a shared understanding with stakeholders.

Density, for all its different dimensions, is a relatively easy concept to quantify compared with inclusivity. Canadian impact development company DREAM, which has a portfolio of $10 billion spanning Europe and North America, believes it can, in the words of head of real estate finance and development Tsering Yangki, “make sure measurement and money are married together,” and find how to track and increase important social performance metrics.

The vehicle for change, the firm’s first annual impact report, seeks to track and improve progress on community, health, and wellness goals within its ongoing 34-acre multiuse ZIBI project, which straddles the Ottawa-Quebec provincial border. As the mini-city grows—it has been in the works for years, in part owing to zoning challenges and protests over the land being sacred to indigenous communities—DREAM will measure three key metrics: affordability, environmental sustainability, and inclusivity, the latter being the most challenging, per Pino Di Mascio, head of impact strategy and delivery.

Creating communities where people have more social interaction and are happier in their environments can be hard to quantify and measure, said Di Mascio, especially without overstepping privacy boundaries. The report analyzes job creation among different groups, especially women-led firms, and attempts to map social interaction and gauge community happiness. DREAM also hopes to preserve the site’s connection to the Algonquin tribe and provide employment for the Algonquin Anishinaabe nation.

Going forward, the development will make sure larger residential buildings, the first of which should open next year, include 30 percent affordable units and explicitly measure—via surveys and staff interviews—how common rooms are booked and utilized and how different social strata are interacting. The goal, according to Di Mascio, is to go beyond property management and focus on community curation, with additional employed positions dedicated to the social well-being of the project.

“With impact investing, you should have data-driven answers about where you’re investing so you’re investing money where you can achieve social good,” Di Mascio said.

That aspect of feedback is key to the work of Deanna Van Buren, a noted restorative justice advocate and prison abolitionist who runs her own Oakland, California, design firm, Designing Justice + Designing Spaces. The studio’s projects often rely on a series of toolkits originally geared toward incorporating the feedback of prisoners in the design of correctional facilities. (Van Buren once taught a course in a Pennsylvania facility.) The scope of these toolkits, meant to help architects design new community centers and spaces for nonprofits by tapping into the needs and experiences of those whom these spaces serve, has since expanded into different areas, including designing spaces for survivors of violence. There’s even a toolkit meant to help developers learn new ways to finance these unorthodox new projects.

“We don’t often talk with users, often just the people in charge,” Van Buren said about architects and the design process. “That’s not really visionary.”

Van Buren argues that these series of exercises and activities—including creating paper and physical models and collecting images in a collage to communicate the values of a new space—can help close the design literacy gap, a crucial barrier to more community involvement and critiques of architecture.

“We live and work and play in architecture, and the fact that nobody knows how to use it as a powerful tool to achieve outcome and results is problematic,” she said. “We have to take responsibility for the fact that people don’t understand these things.”

For Van Buren, this kind of engagement with those most directly affected by a new project is an example of co-learning within the development process, in which the designers and users educate one another. She advocates these steps for any design project. If it’s impossible to improve what one doesn’t measure, perhaps it’s impossible to design for a community without designing with a community.

“Don’t do it to be warm and fuzzy,” said Van Buren. “Do it so you won’t get it wrong.”