The Invention of Public Space

Mariana Mogilevich

University of Minnesota Press

MSRP $30

Current debates around public spaces in New York—the future of pandemic-born streeteries, say, or police-enforced curfews in Washington Square Park—assume that these spaces should be for everyone. Within this discourse, public space is seen as inherently democratic and the place where we celebrate the city’s diversity, among other things. But Mariana Mogilevich’s new book upends this wisdom. The Invention of Public Space challenges the notion that the city’s open or free spaces amount to an “unalloyed, universal good” whose civic underpinnings can be traced to the ancient Athenian agora. It emends and dramatically condenses the historical trajectory of the titular spatial invention, dating it to the 1960s and 1970s, during the John Lindsay mayoral administration.

Mogilevich insists on the point. “New York City in the early 1960s did not have ‘public space’ as such,” she writes. “No one referred to it that way,” here or in any other city. It was only through experiments in inclusive space-making and public participation that the constellation of spaces that are now commonly understood as making up “public space”—parks, plazas, vacant lots, sidewalks, waterfronts, streets—came to be identified by that name. These efforts took on outsize meaning against a backdrop of urban crisis, where design proposals, big and small, could open a door to utopia. “Each space,” Mogilevich writes, “was conceived not as a part of the city or as a space apart from the city but as a metaphor for the city as a whole.”

Through careful presentation of spatial and political experiments that continue to shape the fields of architecture and planning to this day, Mogilevich shows what was and is at stake in urban life. The Invention of Public Space invites the reader to see the city not as a static object, but as the product of ongoing negotiations among people. Indeed, the book’s great strength is the compelling portraits it renders of city officials, residents, designers, and advocates, all with their own assumptions and ideas about what a city should be and how it might be used (and by whom). Throughout, Mogilevich’s precise, engaging writing delivers complex concepts and histories in a tangible way, giving the reader the chance to inhabit the perspectives of this diverse set of actors.

Rather than analyzing shades of publicness—who owns these spaces, really?—Mogilevich foregrounds the processes behind the designs and depicts these places as “physical, lived space.” Introducing the fertile urban design currents that came out of the immediate postwar period, she shows how these reference points guided planners and urbanists inside the Lindsay administration to develop “experiments in open space.” The book drills down into these experiments, with each chapter devoted to a different spatial type, ranging from residential plazas and vest-pocket parks to pedestrian streets and waterfront landscapes. Examining three threads—psychology, participation, and urban scale—through a series of dramatic episodes, Mogilevich shows how ambitious ideals met urban realities to produce results both concrete and ideological.

Urban Design as Public Policy

Reading Mogilevich’s study, architects will likely salivate over how much power and influence designers had in the Lindsay administration. Elected in 1965 as a liberal Republican and reelected in 1969 as an independent, Lindsay understood that space is political and politics is spatial. He was adapting to the times: Amid mass migration and suburbanization—one million Black and Puerto Rican residents moved to New York between 1960 and 1970, while a similar number of non-Hispanic whites moved out—the city saw an increase in economic inequality and calls for racial justice. The urban crisis followed top-down urban transformations and renewal schemes implemented by Robert Moses during his decades-long rule.

Lindsay countered the status quo with a unique formula equating urban design with public policy. In a white paper on the city’s housing crisis, he promised “to make this city—its housing, its parks, its community facilities—for its people.” Mogilevich describes the approach as a “model of fun, freedom, and diversity, enlisting designers and planners in concerted municipal experimentation to create the spaces that would prove it was so.” In a first, Lindsay established the Urban Design Group within the Department of City Planning as a “design experiment laboratory.” Staffed by 15 architects, the group led design and planning studies, conducted design reviews, and coordinated private development.

This was a time for creative bureaucrats such as Thomas Hoving. While in his mid-30s, Hoving made the now-unthinkable career jump from art historian working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s medieval wing to city parks commissioner on the strength of a single white paper. That sketch, for the construction of playgrounds in overlooked areas and marginalized communities, would blossom into an ideological program grounded in “learning and self-actualization rather than standardization and conformity,” Mogilevich writes. Under Hoving, the city hosted Central Park “happenings”—participatory events like costume parties and dance contests—and built adventure playgrounds by architects like Richard Dattner.

As Hoving was busy remaking the city’s playscapes, others in the administration made headway on early sidewalk cafe regulations and experiments in pedestrianization. Lindsay appointed a Sidewalk Cafe Study Committee, which suggested allowing cold-weather enclosures to “bring people back to the streets, thereby reducing the likelihood of crime,” and the Urban Design Group even developed a study of design standards for outdoor eating on Second Avenue. Gay Talese satirically commented at the time that New Yorkers could finally live the cafe life as they would abroad, as long as they were “not allergic to bus fumes and … not poor.” In 2020, streeteries reappeared on Second Avenue, though their future is uncertain.

In another foreshadowing, the first Earth Day celebration, on April 22, 1970, triggered temporary street closings across the city. Designed to reduce air pollution and promote public transport, these closings resembled the Open Streets program Bill de Blasio introduced during the COVID-19 lockdown and were as energizing and politically fraught as their counterparts are now. The near disappearance of manufacturing space, particularly in Manhattan, can also be linked to design and policy decisions of the Lindsay era. Shared spaces in housing developments were contested then as they are now, ranging from super-public plazas to areas minimized in the name of “defensible space.”

Public Participation

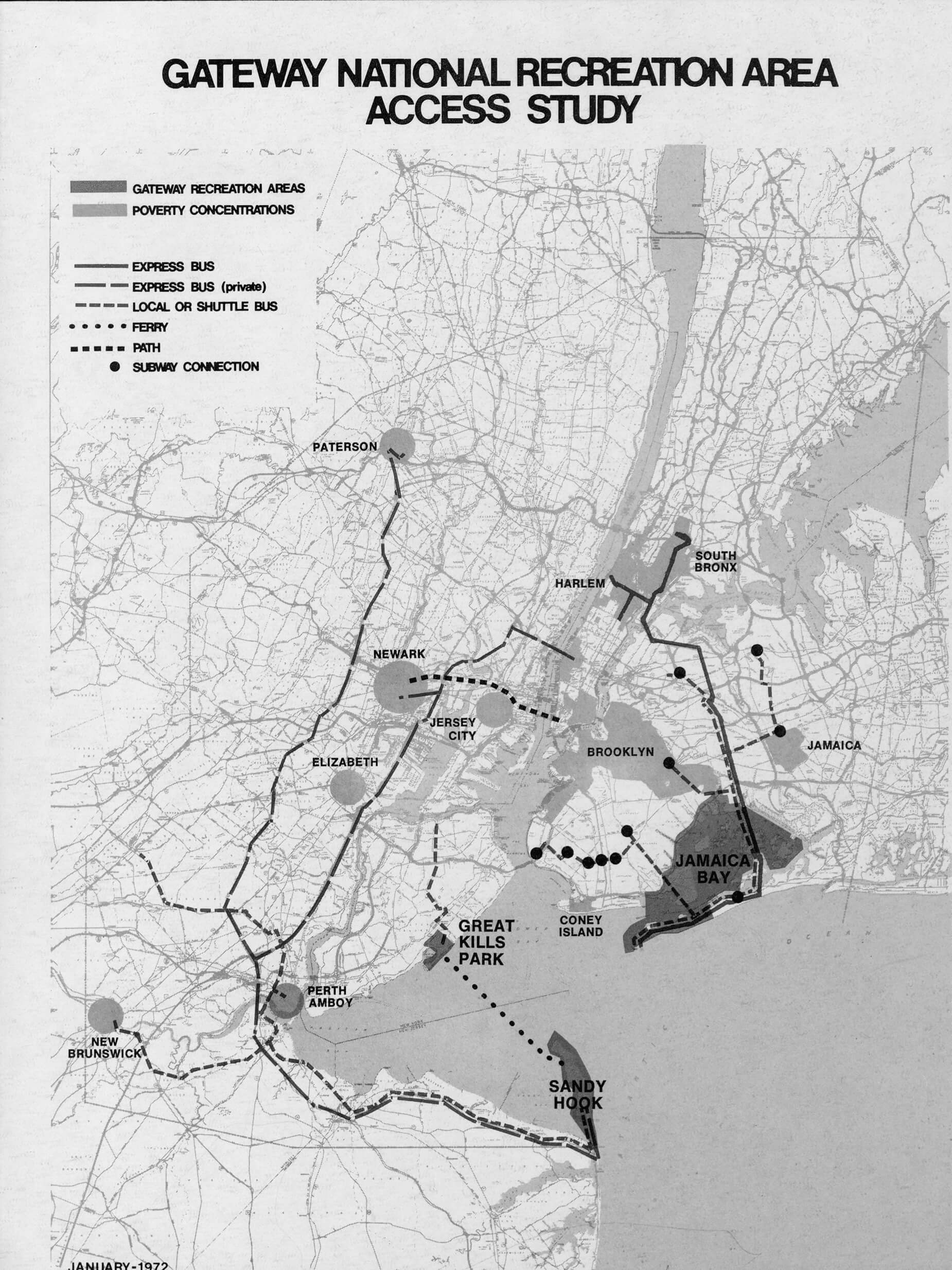

If Mogilevich’s book turns on singular visionary bureaucrats, it also pays mind to evolving modes of public participation in the creation and maintenance of open spaces. These passages are among the most exciting and tragic in the entire volume, revealing how grand ambitions and good intentions can easily falter—especially when sufficient planning and resources for maintenance are lacking. The city’s “vest-pocket” parks program is a paradigmatic example of this denouement. Named for their small size, vest-pocket parks attempted to turn vacant lots from “eyesores into amenities,” Mogilevich writes. The result of disinvestment, white flight, and landlord neglect, empty lots in poorer neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant and the South Bronx were “visible signs of political disenfranchisement.” Already, public space designs of the time moved to privilege user experience over aesthetics; for instance, at Jacob Riis Plaza, fences protecting pristine New York City Housing Authority lawns were torn down and inhabitable, actively programmed play- and landscapes installed in their place. Public participation in design was the logical next step.

The first vest-pocket park opened in Bed-Stuy in 1966. A collaboration between the city with the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council and the Pratt Center for Community Development, funded by two private foundations, the park was greeted warmly by the architectural press, which labeled it a “neighborhood venture.” The characterization was not unearned. Community members participated in design meetings; local children helped with small construction tasks and served as play equipment design “consultants”; and unemployed men from the neighborhood were hired to build the park. Designed by Pratt Institute professor M. Paul Friedberg, the park also featured murals by Pratt art students. Local activists hoped parks like this one would serve as catalysts for further community-led development.

But the new parks quickly fell into disrepair, as the city expected low-income residents to handle facility maintenance. Mogilevich quotes Pratt Center founder and community planner Ronald Shiffman’s damning 1969 evaluation of three years of vest-pocket park experiments: “If it is the intention of any municipality, or community development corporation, to buy time or create a highly visible, but one-shot palliative by undertaking a beautification program, they are in for a rude and well-deserved awakening.”

Learning from “Failures”

Many of the spaces profiled in The Invention of Public Space were ultimately perceived as failures, even by their designers. Following Nixon’s cuts in federal funding for cities and the 1975 New York City financial crisis, they were fenced off, neglected, graffitied, and sometimes demolished. What few were deemed successful, such as South Street Seaport and Battery Park City, were and continue to be “spaces for a circumscribed, generally white and middle- to upper-class public,” Mogilevich pointedly observes. Time and again, she questions for whom these emergent public spaces were designed and for whom they were not. Despite the utopian streak evident in the work of the Lindsay administration, old prejudices persisted.

Portions of this review were written in a COVID sidewalk cafe enclosure and a Bloomberg-era pedestrian plaza maintained by a business improvement district—examples of newer forms of New York public space that are rightly criticized for their commercialization, inequitable distribution across the city, and limited access. Mogilevich acknowledges the validity of these concerns and decries the move from ambitious experiments in democratic space-making to today’s focus on “innovation,” data collection, and an “almost mystical belief in the agency of movable chairs.” But she also invites those who might reject any compromised public space to ask, “Did a noncommercial, geographically distributed, ecumenical urban space ever exist, or had it just briefly appeared possible?”

Mogilevich’s portraits are wonderfully nuanced. Her outlook is ultimately hopeful. Every public space is compromised in some way, and none are as inclusive as we would hope. But that is not a reason to give up. She might agree with architect and theorist Craig L. Wilkins, who writes, “Space is life.” Mogilevich calls contemporary fights for the “commoning” of urban space potentially “revolutionary” and celebrates recent public space designs that welcome diverse gender identities, respond to the concerns of recent immigrants, and support human and nonhuman species. Architects looking to join in the fray must accept that transformations in urban space will not “leave a physical legacy so much as an ideological one.” This timely book squashes naïveté and inspires, leaving the reader energized and better prepared to pursue spatial justice anew.

Karen Kubey is an urbanist specializing in housing and health.

AN uses affiliate links. If you purchase something through these links, AN may receive a comission.