Once it became clear in early summer 2020 that workers were unlikely to return to offices for the foreseeable future, the press wasted no time painting an apocalyptic scene. In New York, a city with a glut of office space, giant real estate developments such as the World Trade Center appeared at risk of permanently losing tenants.

Rumors swirled around Condé Nast, 1 World Trade Center’s flagship tenant, and whether the media company would pick up sticks for Jersey City. In January 2021, the developers of 5 World Trade Center announced the tower would pivot from offices to luxury residences. (After numerous delays, the project has yet to break ground.) Meanwhile, financial turmoil forced the 9/11 Museum, a focal point of the wider complex, to cancel its 20th-anniversary programming. Would the site founder before building works had even concluded?

The panic was not wholly unwarranted: The New York Times reported that as of July, almost 19 percent of Manhattan offices were without tenants, a high point for the city since the 1970s. But though the World Trade Center did see a dip in occupancy over the course of the pandemic (2 percent in the case of 1 World Trade Center), the site is overall poised for growth. The companies that lease the floors within its buildings and the building landlords themselves aren’t worried. The office towers still embody what tenants are looking for: architecturally significant, well-ventilated, daylight-optimized office space with amenities and public space near all the major transit lines.

For Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), spending its first year in 7 World Trade Center with a social distancing protocol hasn’t been ideal, but the thoughtful design of its new office space spanning the 27th and 28th floors of the 52-story building has helped its employees ease into work there. The firm completed the interior project last summer, and up to 30 people now occupy the office daily.

Ken Lewis, managing partner in the New York office, goes into work up to four times a week. “Moving into 7 World Trade Center was a dream for us,” he said. For two decades, the firm was based out of 14 Wall Street, a 109-year-old skyscraper and city landmark. In search of a fresh start, Lewis’s team surveyed other firm projects and historic buildings downtown, but in the end they found the sustainable appeal and open plan of the SOM and David Childs–designed tower too good to resist.

To Lewis, 7 World Trade Center aligns the firm’s ethos with its new generation of partners. “We wanted a space that reflected the way in which we’re working today and how we see ourselves working in the future—in a collaborative environment with daylight, quality air filtration, and transparency,” he said. “In many ways, it was an obvious choice.”

When all employees return to work, 400 people will be spread out over the two floors, which SOM currently subleases from the largest tenant within the building, financial risk assessment firm Moody’s Corporation. Other tenants in 7 World Trade Center include wedding registry site Zola, Moët Hennessy USA, and Fast Company and Inc. magazines, as well as design firm Jeffrey Beers International. According to Silverstein Properties, the landlord and developer, the 1.7-million-square-foot building is consistently fully leased, in part because of timing: It was the first tower to open on-site (starting construction in 2002, completed in 2006) and to attract tenants. It also received a special designation as the first tower in New York City to achieve a LEED Gold certification from the U.S. Green Building Council.

The other completed towers under Silverstein’s purview include 3 World Trade Center, a 2.5-million-square-foot office building finished in 2018, as well as 4 World Trade Center, a 2.5-million-square-foot office tower built in 2013. The buildings are currently 80 percent and 100 percent leased, respectively. Tenants include advertising firm GroupM and tech companies like Spotify and Uber, as well as Casper Sleep and management consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

One World Trade Center, the crown jewel of the site, is separately owned by the Durst Organization and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. When it opened in 2014, it was 55 percent leased. The Twin Towers, for reference, were a hard sell for decades and full occupancy didn’t happen until just prior to 9/11. Before the start of the pandemic, 1 World Trade Center was 92 percent leased.

Durst’s struggle to fully lease the tower has been widely reported over the years. Its latest battle involved Condé Nast, and the publishing company’s parent, Advance Publications, which threatened earlier this year to move some of its operations to New Jersey in an effort to cut costs. Bloomberg first reported that Advance was withholding rent money as it reevaluated its need for such large swaths of office space with so many of its employees now working from home. By early August, however, Advance decided not to break Condé Nast’s 25-year lease in 1 World Trade Center and paid $10 million in overdue rent to the Durst Organization with a plan to continue subleasing some of its 1.2 million square feet of space, a number totaling nearly one-third of the building.

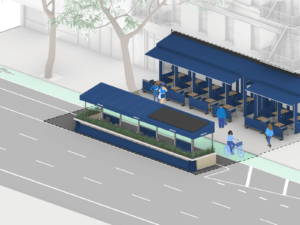

Shareable amenities and mixed-use workspaces are another reason why tenants have been unwilling to pull out of the World Trade Center. In Silverstein’s buildings, tenants have access to amenities from the developer’s entire portfolio, including the terrace on the 17th floor of 3 World Trade Center and the cafe and lounge on the 10th floor of 7 World Trade Center.

“It’s part of this larger trend we’re seeing of a flight to quality,” said Jeremy Moss, executive vice president at Silverstein Properties. “As companies rethink the importance of collaborative workspaces, things like flexibility, functionality, and quality of design and programming are all things that new buildings can offer.”

The 16-acre World Trade Center campus was built with some of these things in mind. Designed by Daniel Libeskind, the master plan featured room for retail, restaurants, office space, contemplation, and connection to the rest of the city via the Oculus Transportation Hub. Kohn Pedersen Fox, the architects behind 5 World Trade Center, recently revealed a new mixed-use design utilizing all of this programming, including 1.2 million square feet of residential space, or 1,325 apartments.

Most of the amenities within the other World Trade Center office buildings, though, are exclusively for employees. The types of foundational amenities included in other recent New York office projects—lobby-area lounges, cafés, and meeting spaces on the ground level—just aren’t possible here.

“As a response to the initial crisis and the then-present threat, 1 World Trade Center, in particular, was built very defensively,” noted Peter Knutson, chief strategy officer of A+I, an architecture firm that specializes in office design and development. The lobby is a very controlled environment for both the building workers and the visitors to One World Observatory.

“Buildings at the World Trade Center will always have to contend with the fact that they are occupying a living memorial and the reality is that there aren’t many places in the world that have to contend with that,” Knutson said. Certain things like heightened security were integrated as a form of precaution. Despite this, for many visitors—and office workers—what was once Ground Zero is now an inviting public space. It’s only within the office portion of each tower that exclusive access is a must.

One of the main reasons why the World Trade Center may be doing better with its commercial vacancy rates compared with the rest of the city is, in large part, the Financial District’s recent growth as a residential enclave. As more young professionals moved to the neighborhood post-9/11, so did creative companies following in the footsteps of Condé Nast. Today, the mixed-use, compact nature of Lower Manhattan is attractive to people who want everything in their backyard, including work.

“The lines where we live and work are increasingly blurring,” said Moss. “The World Trade Center has become a place of constant creative energy, much like a college campus, with virtually every industry imaginable represented here.”

Sydney Franklin is a journalist based in New York and a former AN associate editor. She recently wrapped up a real estate reporting fellowship at The New York Times.