In March 2021, the Biden administration announced an ambitious plan to dramatically expand the country’s wind energy output to 110 gigawatts by 2050. Much of this expansion will take place on the Eastern Seaboard, and while Senator Joe Manchin’s machinations may jeopardize the financial largesse of federal support, New York State, in line with its goal to achieve a carbon-free electricity system by 2040, aims to take the lead in this massive undertaking with a bid to power 2.4 million homes across the state with offshore wind energy.

The growth of the offshore wind industry also presents a singular opportunity to reimagine the working waterfront of the metropolitan region. The nascent industry is in the process of reinvigorating long-dormant stretches of New York City’s once preeminent port, which could see a revival of maritime freight and subsequent reductions in truck-based emissions, all while providing thousands of middle-class jobs.

A vast political and commercial coalition, including the likes of longtime working waterfront champion Congressman Jerrold Nadler, has been pushing the movement forward.

“It was part of the Green New Deal before it was even hip to talk about the Green New Deal,” said Nadler’s district director Robert Gottheim. “We have been approaching this issue through economic development, jobs, and transportation. If the port industry becomes more efficient, they will be able to load a ship in Okinawa or Rotterdam or China, and drop off cargo in Brooklyn. And, through the redevelopment of a working waterfront, we can address asthma rates in the poorest neighborhoods of the city and provide well-paying jobs.”

There are several infrastructural and geographic attributes that played an outsized role in the development of the New York City region into a global commercial center. The construction of the Croton Aqueduct, and later the Catskill and Delaware Aqueducts, accommodated exponential population growth. The subway system facilitated this population’s movement across the five boroughs. But New York Harbor, one of the largest harbors in the world, with access to the continental interior through the Erie Canal and links to a vast web of freight rail lines, set the metropolis apart from its peers.

By the beginning of the 20th century, New York Harbor was the primary American entrepot for foreign trade, handling nearly two-thirds of the country’s imports and over one-third of its exports. Thousands of docks and piers jutted into the harbor to meet the great constellation of cargo ships and tankers, barges and ferries, and steamboats and ocean liners entering the harbor’s waters. The shipping industry employed tens of thousands of longshoremen and nearly half a million other workers. However, the rise of containerization and the construction of Port Newark-Elizabeth, coupled with the demographic and economic shift to the Sun Belt and the ascent of interstate trucking, rendered much of the waterfront industry obsolete.

Improved port infrastructure will necessarily play an integral role in the development of New York’s offshore wind industry, and this will be largely a matter of size: Offshore wind components are gargantuan and getting bigger—the state-of-the-line towers are approximately 450 feet tall, while the blades are now over 300 feet in length—and this raises complications for rail or truck transport. The components have to be loaded onto a wind turbine installation vessel and carted out to sea, where they are put together atop floating or monopile foundations that transmits electricity to offshore and onshore substations. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) has identified five sites as key nodes for the offshore wind supply chain and wind turbine staging: Montauk Harbor, Port Jefferson Harbor, South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, Port of Coeymans, and the Port of Albany.

The South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (SBMT) will be the most significant maritime facility within the NYSERDA-led scheme. The site is a 73-acre intermodal transport hub located squarely between Industry City (formerly the Bush Terminal) and the waning industrial mecca of Gowanus and Red Hook. It was built as a container terminal and break-bulk and general cargo facility in the 1960s, but growing ship size rendered the facility obsolete by the 1980s, and it was largely abandoned.

In 2018, the New York City Economic Development Corporation initiated the process of reactivating the terminal with a significant $115 million investment for infrastructural upgrades. That same year, Sustainable SBMT LP, a partnership between nearby port facility operator Red Hook Terminals and developer Industry City, was awarded a long-term lease for operation of the site. Sunset Park-based Grassroots organization UPROSE played a critical role in laying the groundwork for the site through their Green Resilient Industrial District proposal in 2019, which staved off attempts to rezone the SBMT for other uses. Later, in January 2021, Norwegian state oil company-turned-wind-energy-behemoth Equinor and strategic partner BP were awarded offshore wind energy procurement grants to produce 3.3 gigawatts of power for New York State. The Port of Albany will serve as the manufacturing hub for wind tower and transition pieces, which will be loaded onto ships and barged down to a staging ground for the offshore wind farms at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal. The latter will receive a further $400 million in upgrades, to be split evenly between NYSERDA and the Equinor/BP joint venture.

Across New York Harbor, at the southernmost edge of Staten Island, a different but equally ambitious offshore wind project is taking shape. The Atlantic Offshore Terminals is a privately owned infrastructure real estate company with plans to transform a 32-acre site on the Arthur Kill tidal strait into a state-of-the-art port facility for offshore wind staging and assembly. The ground-up project is led in collaboration with the state, and Empire State Development recently submitted a grant for the Arthur Kill Terminal (AKT) to the U.S. Department of Transportation for approval. Critically, the AKT is the only staging and assembly port proposed for the Eastern Seaboard with unrestricted clearance—it is located south of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, while the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal is several miles to the north.

“Due to the geography and configuration of ports on the East Coast, there are very few locations where you’ll have co-located manufacturing and staging and assembly,” said Atlantic Offshore Terminals CEO Boone Davis. “We just don’t have sites like they have in Europe, which have hundreds and thousands of acres with no bridge restrictions, and where you can make a lot of these parts and assemble them and then load them and deploy them directly to wind farm sites. These ports, like AKT, will sort of serve multiple functions on the East Coast, and our hope is that there will be a lot of additional manufacturing port development occurring in parallel and following staging port investments underway in the United States.”

The utility of the fast-growing offshore wind farm industry extends beyond green energy and job creation within the New York metropolitan region: There are numerous avenues by which a working waterfront can also increase citywide resiliency and access to parkland. One group advocating this approach is the Waterfront Alliance, which, since its founding in 2007, has steadily assembled a broad regional coalition of over 1,100 organizations to realize this goal—ranging from the Billion Oyster Project and Riverkeeper to manufacturers and dry docks.

“People are often quite surprised to learn about how much maritime activity still goes on in the city and how much potential there is for growth,” said Waterfront Alliance vice president of programs Karen Imas, “and that interest brings growing attention to what the future of the working harbor will look like as a combination of shipping, ferries, potential renewable energy, and offshore wind, mixed-use industrial sites, and green infrastructure.”

In 2015, the Waterfront Alliance launched the inaugural iteration of the Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG), a voluntary rating system and set of guidelines similar to LEED certification for projects located on the waterfront. “The idea is to change the way that designers and developers are looking at waterfront projects,” Imas said, “but also to encourage the city and the state to look at the permitting processes through a lens that can drive more innovation, ecology, and resilience for the waterfronts that we need today.”

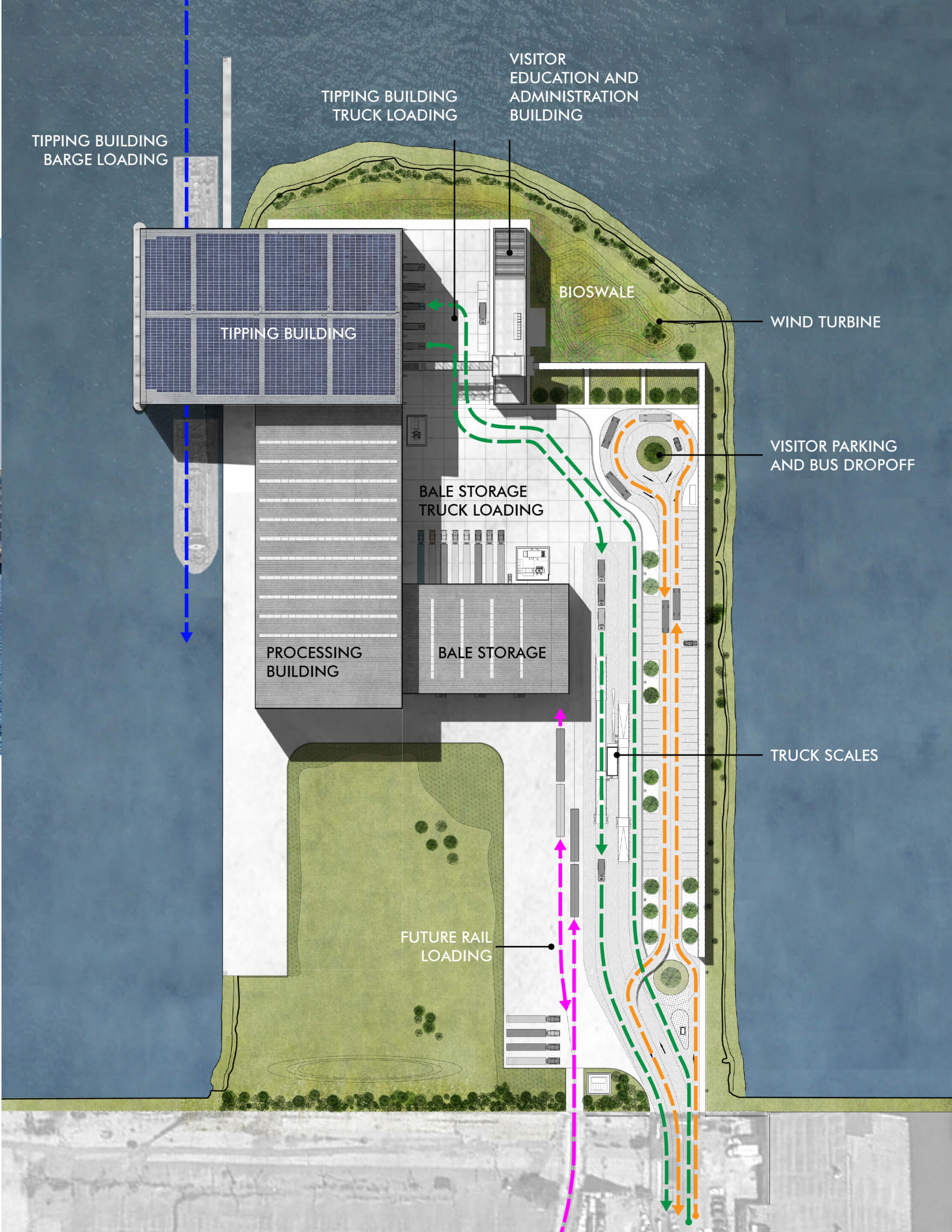

While the exact manner in which such measures will or could be implemented at the SBMT or AKT is still unclear, there are recent projects that set a precedent for the incorporation of WEDG guidelines into waterfront industrial sites. One such site is the Sunset Park Materials Recovery Facility, located at the northern quay of the SBMT and operated by international recycling company Sims Metal. The facility was designed by Selldorf Architects and can accommodate 20,000 tons of refuse a month freighted in by barge, rail, and truck. It also makes room for approximately 50,000 square feet of green space featuring native plantings, bioswales to handle stormwater, and breakwater barrier reefs built with dredged material from the Kill Van Kull, which will support bird and marine life. The facility is also semi-open to the public through the Recycling Education Center, which provides access to community and school groups.

To the north, in the Bronx, the McInnis Cement Marine Terminal also portends resilient landscaping to come. The 28-acre facility is the New York City outpost of the Quebec-based cement manufacturer. With the help of a new pier and piping system, it has the capacity to barge 5.5 million tons of cement annually from the St. Lawrence River, which translates to an approximate reduction of two million truck miles per year. On the ground, a team led by WXY incorporated a 30-foot-wide public walkway adjacent to 3 acres of restored wetlands that, with a system of breakwaters, can attenuate wave height by approximately 60 percent in the event of a 100-year storm.

The economic and political will is there to establish New York as a leader in offshore wind energy, and with that will come a rare opportunity to comprehensively reimagine the city’s harbor with a working and resilient waterfront. Let’s hope that it doesn’t go to waste.

Matthew Marani is studying city and regional planning at Pratt Institute and writes about architecture and urban design.