Born in Amersham, England, in 1945, Chris Wilkinson began his architectural career as a student at the Regent Street Polytechnic in central London in the early 1960s alongside three members of the band Pink Floyd. While many architects of that era went on to work in the public sector, Chris headed to Denys Lasdun’s office to work on the National Theatre. He then took a summer off in the Greek islands, returning armed with a clear vision that the future of architecture lay with new possibilities of technological innovation. After spells at Foster Associates working on IBM projects, at Richard Rogers Partnership on the Lloyds Building, and with Michael and Patty Hopkins on a project for Greene King, he formed Chris Wilkinson Architects in 1983. For a while, he retained a part-time presence at Hopkins to oversee a project for Willis Faber, which I was working on too as a recent graduate of the Architectural Association.

The practice’s first home was in a corner of Troughton McAslan’s office in Notting Hill. Later we took space at Horseshoe Yard, just behind the Yves Saint Laurent boutique on Bond Street (another branch of which became an early project).

Our working relationship at Hopkins led to me joining Chris full-time in 1985 and forming our partnership in 1987. Ever since his student days, Chris had been fascinated by long-span structures and the Miesian idea of universal space. Fortunately, his 1991 Supersheds book caught the attention of Roland Paoletti, who was commissioning architect for the Jubilee Line Extension at the time, and this led to two break-out projects for us – Stratford Market Depot (completed in 1998) and Stratford Station (1999). From the teams that worked on these projects emerged several future directors of the practice—Paul Baker, Oliver Tyler, Stafford Critchlow, and Dominic Bettison. The commitment of these talented people enabled the practice to flourish, working initially alongside either Chris or myself or both of us in what was to become WilkinsonEyre.

Around the turn of the millennium, lottery funding was creating great opportunities in the cultural sector and Chris led much of our work in museums and visitor attractions in that era, including Magna in Rotherham, which won the Stirling Prize in 2001, Explore@Bristol (now We The Curious) and the National Maritime Museum in Swansea, Wales. Many exhibition design and education projects were to follow, including The Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth (2013)—a project particularly close to Chris’s heart. But it is perhaps the 1997 Challenge of Materials Gallery at the Science Museum that best sums up Chris’s ethos of ‘Bridging Art and Science’, with its beautifully delicate suspension bridge made up of glass treads and hundreds of wires with interactive sensors. The phrase went on to become the title of the practice’s first monograph. This book led to Kurt Forster’s invitation to the practice to participate in the 2004 Venice Biennale.

Chris was always keen to broaden the practice’s experience into new sectors. On the back of an ideas submission for DfES exemplar schools, came a series of built schools, including the John Madejski Academy in Reading and the first BSF schools in Bristol (all 2007). The practice went on to work extensively on university projects, including the Earth Sciences Building in Oxford, the Exeter University Forum, and several buildings for Queen Mary University of London. Chris’s belief in technology as a solution to climate-related challenges is perhaps best illustrated in two contrasting projects that share angular forms that I always tend to attribute to Chris’s love of jazz music: firstly the Siemens Technology Centre in London’s docklands 2012 and secondly Oxford Maggie’s Centre (2014), a cross-laminated timber structure on pilotis in a wooded setting, which was one of his proudest achievements. Chris remained interested in architectural education, and his academic appointments included Visiting Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago (1997–98) and teaching at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (2003–04).

During this period we were also very focused on designing bridges, and it was perhaps our second Stirling Prize win for the Gateshead Millennium Bridge in 2002 that brought international visibility. We knew we could bring our skills in ‘elegant engineering’ to other areas, and new expertise in super high-rise buildings was honed in the 104-storey Guangzhou IFC Building (briefly the tallest building in the world). More recent WilkinsonEyre towers are completed or under construction in Toronto, the City of London and One Barangaroo in Sydney – a building inspired by Chris’s concept of interweaving sculpted ‘petals’ that emerged from his design for a sculpture to mark the Scottish Border in a competition organised by Charles Jencks. The vision shared by Chris and I, and indeed all the WilkinsonEyre directors, is unchanged since the early days—architecture of elegant engineering realized through close and cross-disciplinary collaboration. The cooled conservatories at Gardens by the Bay in Singapore—perhaps WilkinsonEyre’s best-known international project—are a great example of this founding vision, conforming to Chris’s belief that a single ‘beautiful idea’ should be at the heart of every design.

Chris was elected to the Royal Academy (RA) in 2006. In parallel with his faith in technological innovation as a solution for environmental challenges, his involvement at the RA further stimulated a passion for painting and drawing as a means of developing and recording ideas in a clear and unambiguous form. Chris’s commitment to sketching transcended design to become a way of seeing the world, as evidenced in his portfolio of travel sketches published by the RA in 2019. Although Chris had started to reduce his time in the office in recent years, there are two projects he remained very close to: A master plan for the Wellcome Genome Campus at Hinxton near Cambridge filled him with excitement and enthusiasm, while the Dyson Art Gallery at Dodington fulfilled a longstanding desire to design an art gallery. This latter project continued a 25-year working relationship and friendship with Sir James Dyson, which has produced several buildings on separate campuses as well as shops in London, Paris, and New York. The Gallery will represent Chris’s last design, and it is poignant that he won’t see it built.

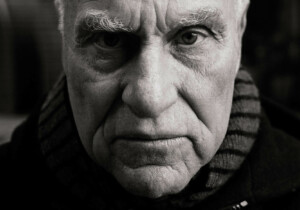

Chris always got on well with clients, collaborators, and colleagues, with a personable, modest nature belying a quiet determination. Always wanting to push forward and try out new ideas without losing the design discipline and attention to detail of our high-tech roots, Chris continually sought to bring some of the freedom he found in fine art into architecture.

Chris died unexpectedly on December 14, 2021. He is survived by his wife Diana, sister Liz, and children Zoë and Dominic.