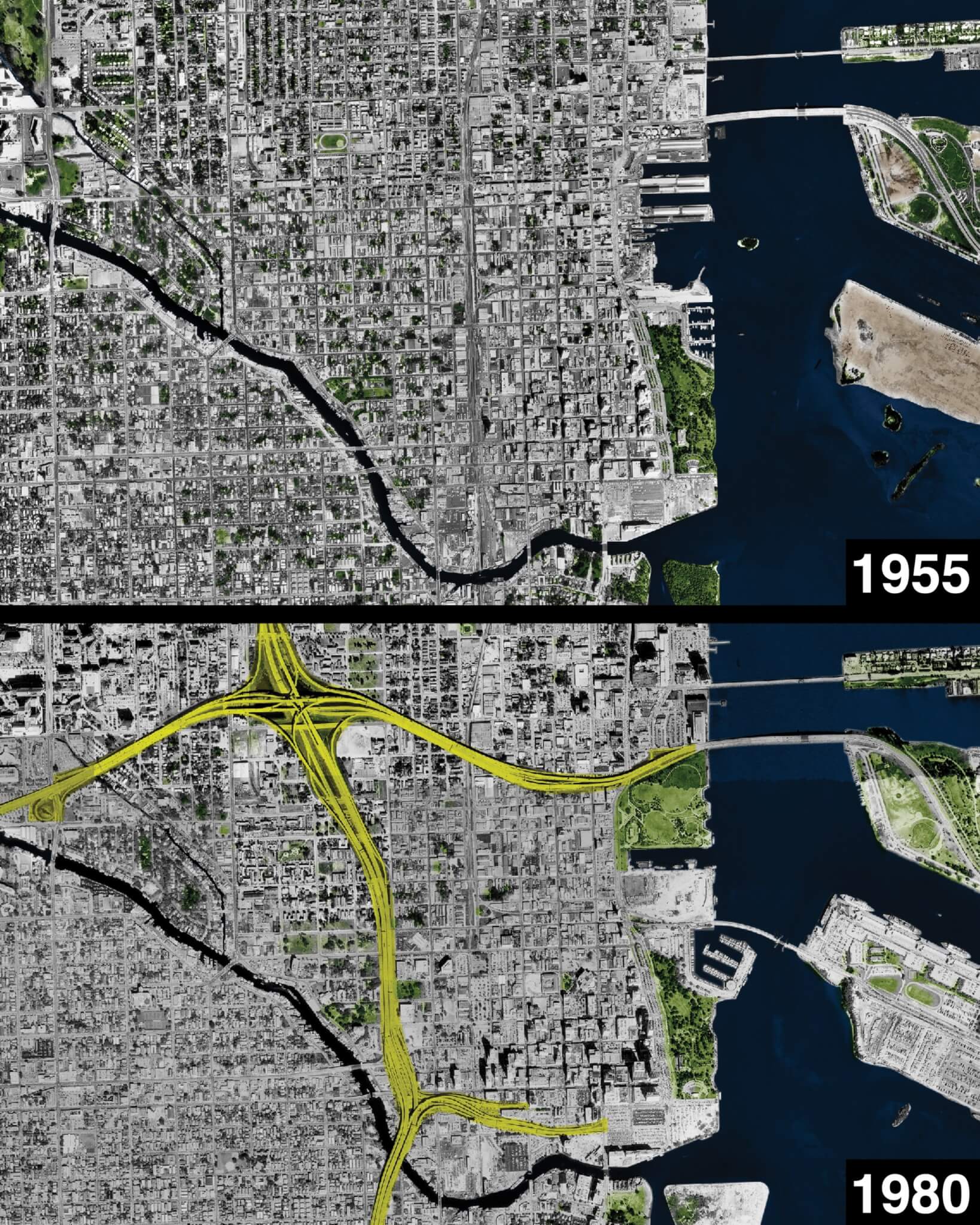

Located at the mouth of the Miami River on the shores of Biscayne Bay, Downtown Miami, like the centers of so many American cities, is ringed by a loop of midcentury interstate highways. These highways divide the city along racial lines, physically isolating Downtown (and the “Millionaire’s Row” neighborhood of Brickell) from the adjacent neighborhoods of Overtown and Little Havana, the historic hearts of the city’s Black and Latino communities.

On foot, accessing the neighborhoods surrounding Downtown requires navigating the maze of broken streets and high-speed arterial roads that abut the highways. Rather than pursuing ways to better connect the city, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) is spending nearly a billion dollars to widen the interstates.

The portion undergoing the most drastic widening is I-395, which connects I-95 to Miami Beach. The highway was originally built through the commercial heart of Overtown, the city’s “Colored Town” during the era of Jim Crow segregation. In the 1960s, construction of this freeway required the destruction of hundreds of businesses, dozens of churches, and several schools, as well as the forcible relocation of over 12,000 residents—nearly all of them Black.

Similar to the way the federal government enabled the destruction of roughly 1,600 Black neighborhoods between 1940 and 1970, municipal and state planners (using federal funds from the 1949 Housing Act and the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act) deemed Overtown to be a “blighted slum,” as described by N. D. B. Connolly in A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida. As was typical of government planning at the time, the vibrant urban reality of Overtown was either ignored or held in contempt.

Overtown was no slum. Founded in 1896 during the era of official government segregation, Overtown was one of the few desirable places Black Miamians were permitted to live until the 1960s, populated with large communities of Caribbean, Latin American, and South American immigrants, as well as migrants from across the American South. The neighborhood became known as the “Harlem of the South,” owing to its booming economy and entertainment scene. Overtown was centered on Second Avenue, known as Little Broadway, and its streets were lined with hundreds of Black-owned businesses, including “dentists, law offices, restaurants of every flavor, laundries, beauty salons, and drugstores,” Connolly wrote. Between businesses were “wide, large brick and stucco homes, some with two stories, large front porches, and, occasionally, two and three bathrooms to spare. These belonged to Black Miami’s professional class.”

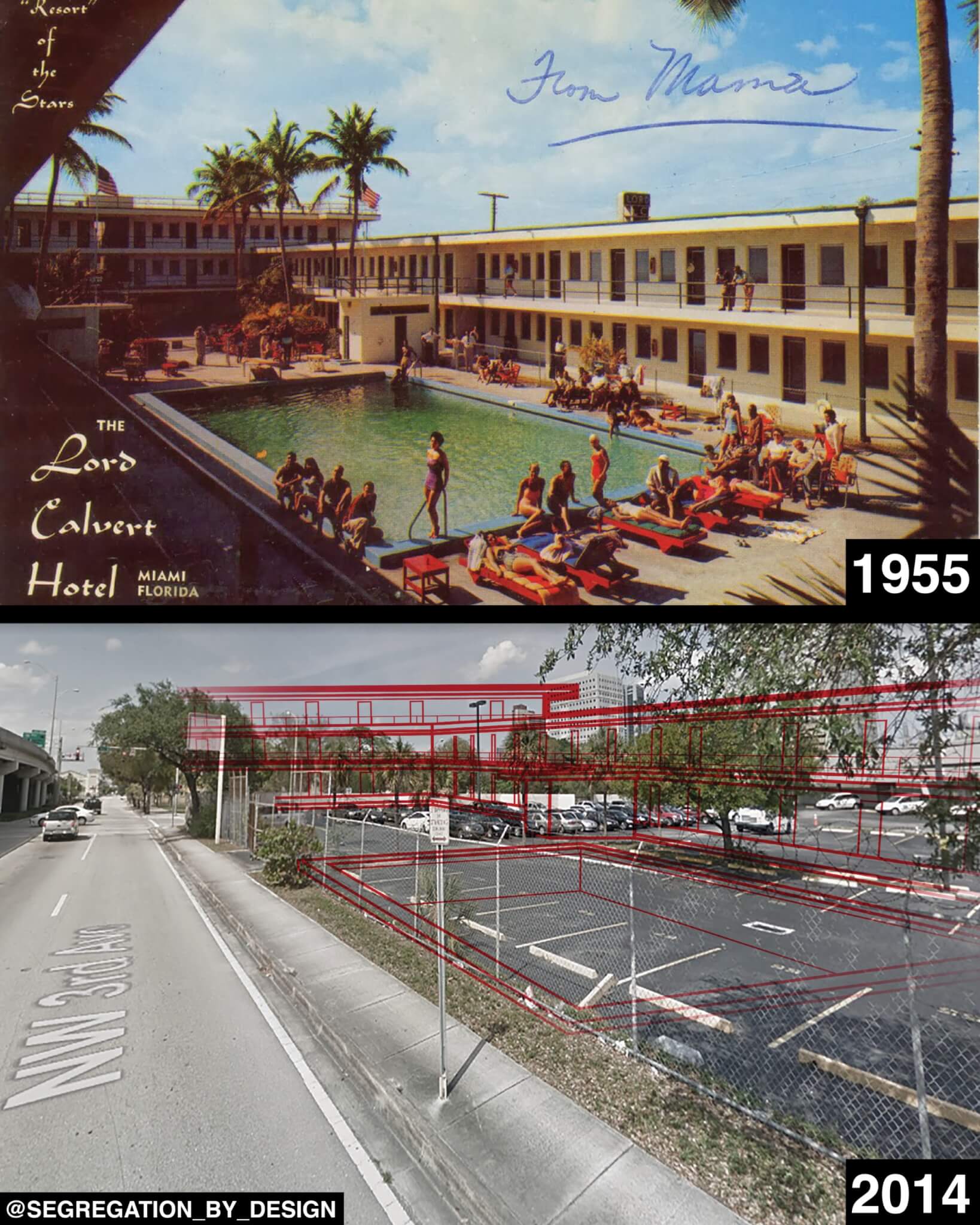

By the 1950s, Overtown was the center of nightlife on the mainland for Miami’s Black, Latino, and white populations alike. Similar to the popular South Beach neighborhood on the barrier island opposite Biscayne Bay in the “whites only” city of Miami Beach (where nonwhite people were required to obtain visitors’ “passes,” which came with a 6 p.m. curfew), Overtown in the 1940s and ’50s was a riot of art deco and streamline moderne, awash in neon and vibrant marquees of all colors. World-renowned musicians and entertainers such as Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, and Nat King Cole would often perform in Overtown’s clubs and theaters yet were barred from staying in Miami Beach because of the color of their skin. Venues such as the Knight Beat Club at the Lord Calvert Hotel, the Harlem Square Club, and the Lyric Theater ensured that Second Avenue lived up to the Little Broadway nickname. With its many hotels featured prominently in the Green Book, a travel guide that listed businesses that would accept Black customers, Overtown became a vacation destination for Black Americans from around the country.

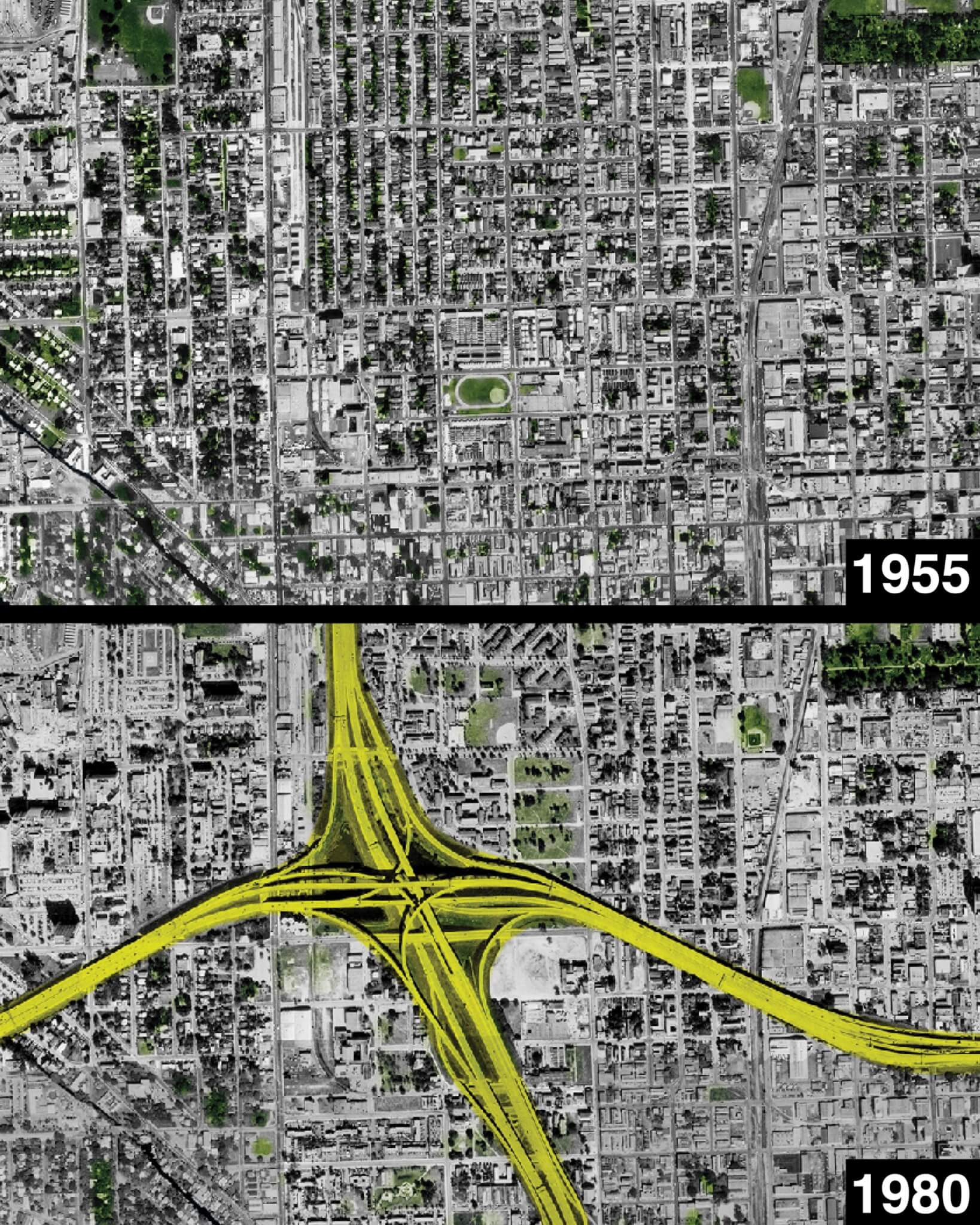

By the 1960s, much of the neighborhood had been leveled for the construction of I-95. With 90 percent of its funding sourced from the federal government via the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act, the City of Miami seized much of the neighborhood through eminent domain, offering property owners deflated prices and removing renters with no compensation. The population of the neighborhood dropped from roughly 50,000 to around 10,000. As Connolly found, “The resulting disruption and pain many of these [highway, urban renewal, and slum clearance] projects wrought was not, as some have argued, the result of some political accident or bureaucratic misstep on the part of otherwise earnest housing reformers. Displacements were intentional. They represented, for growth-minded elites, successful attempts to contain Black people and to subsidize regional economies with millions in federal spending.”

Since the mid-20th century, urban highway construction has worked as a powerful tool to segregate and demolish communities of color, not just in Miami but in nearly every city in the U.S. These imposing roadways served—and serve—as physical barriers that perpetuate racist policies like redlining, as they inscribe the red lines on the map into the built environment. As a result, walls of concrete and veils of smog and pollution grew to separate Black and brown communities from white ones.

Construction of I95 in Miami required the forcible relocation of over 12,000 residents—nearly 100% of them black. Using eminent domain, the gov’t seized buildings across the heart of Miami’s black community in Overtown, offering owners well below market rate—and renters nothing. pic.twitter.com/kgHE76GmJQ

— Segregation_by_Design (@SegByDesign) November 14, 2022

Although government-led segregation is usually discussed as history, for the communities that remain divided by these highways, it is anything but history. Moreover, considerable public health impacts persist: All three census tracts within Overtown are above the 95th percentile for asthma prevalence, a statistic directly attributable to the exhaust and particulate matter from vehicles traveling on the intruding highway. A recent study led by Dr. Peter Muennig at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health further demonstrated this causality by looking at the South Bronx, which is also bisected by I-95 in the form of the Cross Bronx Expressway. In that community, nearly every census tract is in the top percentile for asthma prevalence.

Increased investment in these urban highways threatens to inflict further harm. In Miami, despite protests from the community and alternative highway-to-boulevard design solutions offered from the University of Miami, the FDOT is barreling ahead with its widening project, nearly doubling the width of the highway in stretches between Downtown and Overtown. Claims that higher overpasses, new parks, and landscaping will “reconnect and revitalize” Overtown fly in the face of historical precedent. In the 1970s, Miami attempted to reclaim land under overpasses by building playgrounds and parks, only to let them completely deteriorate in the ensuing years through lack of maintenance. Limited light, poor air quality, vehicular fluid runoff, and dangerous pedestrian access make these areas untenable as park space.

It is telling that in the official renderings for the park project, named the Underdeck, the highway structure itself is represented only by thin lines, almost entirely invisible. It was also disappointing to read in The Miami Times that, despite initial cooperation from the state, Black architects felt pushed out of the Underdeck’s planning processes. In 2017, the FDOT chose a proposal for the Underdeck designed by a joint venture of Miami-based Black architects, including Ron Frazier, Neil Hall, and Zamarr Brown, which was to include a Heritage Trail highlighting the history of Black Miami through a series of art installations and monuments. However, between 2017 to 2019 the team heard nothing from the state, after which the FDOT released new designs without mention of the Heritage Trail. Expressing his frustration to The Miami Times, Frazier said, “The same thing is going to happen to Overtown that’s always happened to Overtown and all the other Black communities that these interstate highways and other stuff are going through: It’s just going to become a thing of the past, and nobody is ever going to remember what happened in that area.”

As Frazier highlighted, rather than being the rare exception, projects like this one fit a long-standing pattern of how the U.S. continues to force highways through communities with the least political power to resist. A 2021 article in The Los Angeles Times found that expansions of existing highways have displaced more than 200,000 people nationwide over the past three decades, predominantly in nonwhite neighborhoods. The U.S. Department of Transportation estimates the total number of people displaced since the creation of the interstate system in the 1950s to be well over one million.

Widening in Miami has already claimed a dozen more city blocks in Overtown. Planned expansions in Houston; Austin; El Paso; Portland, Oregon; Los Angeles; and Shreveport, Louisiana, threaten thousands more across the country with the loss of their homes. Unfortunately, the recently passed Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will continue to feed our national appetite for highway widening. Despite a well-intentioned $1 billion allocated to reconnect communities isolated by highway construction, that law provides far more for the highways themselves: over $273 billion, much of which is likely to be used for future expansions.

Additionally, the Inflation Reduction Act threatens to fund future highway widening. By emphasizing the funding of electric vehicles at the expense of more equitable and sustainable modes of transit, the federal government is choosing to repeat past mistakes and encouraging cities and states to do the same. Demolishing someone’s home for the convenience of a suburbanite driving an electric car is hardly better than having cars powered by gasoline.

We shouldn’t double down on the failed urban highway planning that keeps Americans divided from each other. Rather, cities like Miami should look to the example of cities like Seoul, South Korea; Paris; San Francisco; Rochester, New York; and others that have embarked on massive highway removal campaigns. In Seoul, the removal of a hulking elevated highway (combined with a significant investment in the expansion of the Seoul Metro) has been a significant boon for the city’s CBD. The Cheonggyecheon—the park and stream that replaced the highway—has become one of the most popular spots in the city. In San Francisco, the removal of the Embarcadero Freeway reconnected the city with its waterfront, with spectacular success. Rochester demolished the freeway loop around its downtown, reconnected the grid, and built affordable housing on the former right-of-way.

For the U.S. to adapt to a changing, urbanizing world, the federal government must reckon with the automobile-based segregation it has encouraged for the past 70 years. It should instead invest in public transit, walkability, and reconnecting communities.

Across the country, cities should follow Rochester’s lead and recognize that these hulking concrete structures are the errors of previous generations. Tear them down. Let the people—and cities where they live—heal.

Adam Paul Susaneck is a New York–based architectural designer and the founder of Segregation by Design, a project that analyzes the destruction of communities of color in American cities due to highway construction, urban renewal schemes, and the legacy of redlining. After earning his BA at UC Berkeley and MArch from Columbia GSAPP, he is currently pursuing a PhD in architecture at TU Delft.