The brainworms that grow in your head after being around architects can, after a few years, reshape how you see the world. After sitting through talks and presentations by architects and design professionals—those “do-gooders” who tout low-bono work for the “underserved”—I began to question the word dignity. In design, dignity is too often presented as something to be provided to or conferred upon others; designing low-income housing or public schools gives dignity to those who, presenters seem to say, didn’t already have it. But that’s a shitty way of moving through the world, assuming that poor, queer, or marginalized people and children lack dignity on their own terms, as their own right by virtue of their humanity.

In March, Deem, a semi-annual journal of architecture and design, teamed up with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) to hold their first-ever symposium. The title? Designing for Dignity.

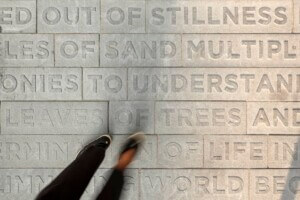

Again, the D-word, I thought as I strolled into the MCA’s Edlis Neeson Theater on a chilly Saturday morning. But throughout the day’s program, which featured emerging and established professionals in art, design, urban planning, and more, conveyed a different way of thinking about dignity: Design doesn’t provide dignity; instead, its practice can affirm it.

Architect, artist, and “trespasser”—as Rick Lowe once called her—Amanda Williams kicked off the day’s events as the keynote speaker and started her talk by expanding on the phrase “social practice.” While the term might elicit an image of, say, Rirkrit Tiravanija serving Thai soup to eager gallery visitors, Williams sees social practice as being in community and making something together.

“People ask me, ‘Well how did you engage the community?’,” she said, facetiously mocking the question. “I am the community; these are my neighbors,” she continued, pointing toward a photo from her Color(ed) Theory project which depicted several people painting an abandoned house bright blue. She went on to present a survey of her work, highlighting various projects that were included at the MCA. Among them were She’s Mighty, Mighty, Letting It All Hang Out, a small room entirely coated in gold leaf that visitors could view from a small opening but could not access. Rather than following the usual artist talk routine of showing finished images and speaking to the work’s meaning, Williams included photos of the installation, again noting that the people working with her to install the leaf were friends and neighbors; they were making something together. Working together, it seemed to Williams, is a different type of social practice—an “unsocial practice.” Unlike a normative social practice definitions encompassed by the all-too common trope of “community engagement,” Williams is “socially practicing” through collaboration.

Practicing socially is not a tidy business, an idea that became very clear during the afternoon talk by Ramon Tejada, a graphic designer and educator at RISD. Tejada spoke about his practice of “puncturing,” a process and pedagogy that “defines and redefines our accepted standards and foundations.” He said this makes “holes” for non-western/European/Anglo experiences and perspectives that “foster a pluralistic imagination.”

In the classroom, Tejada practices puncturing by rebuilding design history alongside his students based on their unique backgrounds and priorities. For example, he teaches color theory in a way that allows students to develop their own theories based on cultural and personal relationships with colors. One project, completed by his student Mahek Vohra, deconstructs a photo of her parents when they were young, pulling colors from the photograph to narrate their story. His Decolonizing Design Reader is an ongoing document that since 2018 has amassed ideas, sources, annotations into an open Google document as a collage of images, lists, links, YouTube videos, and more. It all felt like a mess: His slides were filled with GIFs overlaid with slime-green text and numerous Miro-board screenshots. But the mess is the point: Puncturing is a slow process filled with unknowing and, therefore, prone to entropy. Yet it is also how we discover each other, our unique points of reference, our own cultural singularities. Dignity, it seems, is recognizable in the disarray.

New York–based designer Annika Hansteen-Izora also made a direct correlation between cultivating untidy digital spaces and dignity. Their presentation about “the garden” of the internet asked the audience, “Are the ways that online spaces are designed dignifying users?” The answer is, of course, no: Anyone who has scrolled through Twitter arguments or gets accosted by endless Instagram weightloss videos knows that there is no dignity in that experience. Those spaces are designed, they said, to “privilege impulse over intentions.” They exploit the spectacle, and that design itself is an orchestrator of our collective attention.

Hansteen-Izora believes that internet spaces should be more like a garden: a space to explore, to allow oneself to wander and allow our attention to drift to specific ideas and objects; a place where metaphorical pollination can occur. We need to design online spaces where our “values, agency, and body-mind are honored and protected,” they said. As such, they designed an app called Somewhere Good, a voice note–based platform that allows people who hold marginalized identities to connect and share knowledge. Users respond to daily prompts with voice notes, inciting conversations that can be enriched by PDF and photo attachments. Users can also host in-person gatherings or connect IRL in Something Good’s hub in Bedford-Stuyvesant. But don’t expect networking—it’s about play and joy, they emphasized.

The event itself was staged like a garden: The pop-up bookstore designed by Norman Teague created a hub to mingle, read issues of Deem, and chat with attendees about what they saw and heard. Frequent breaks between panels were chaotic: The auditorium’s narrow walkways were crowded with friends catching up, and the bathroom line was a raucous reunion. I spilled coffee on someone while vigorously shaking their hand. The event timeline was wrong—turns out, it didn’t end at 4:00 p.m. like the website states. I arrived late to a few panels and had to leave early. I was joyfully on “Indian people time,” as my sister calls it, meaning whatever you miss will eventually come to you in other ways.

The Deem symposium helped reframe dignity; it solidified that designers aren’t uniquely equipped to be leaders or politicians “giving” things out that then shape a dignified life. The mess, the garden, and the social practicing are all means to enjoy our already dignified selves.

Anjulie Rao is a journalist and critic covering the built environment.