The wicked problem called Penn Station may, at long last, have a solution. Recently, a proposal by Italy’s ASTM Group and HOK emerged as some observers’ preferred option. On April 17, Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) joined the team. It is neither the optimal solution in all parties’ eyes nor the railroaded political fix that many feared, but it appears to value rail service and public space as its central priorities.

Penn Station and civic contention have been inseparable for six decades. The one point that commuters, architects, planners, activists, and oligarchs of real estate, entertainment, and sports agree on is that the station, the region’s infrastructural pain point, must change. Designed for fewer than 200,000 daily passengers and now subjecting over 600,000 travelers per day to conditions more suitable for scuttling rats than for civilized people, let alone the deities invoked by the oft-quoted Vincent Scully line, Penn Station is a magnet for revisions. On its site, the irresistible forces of design and transportation expertise meet an apparently immovable object: Madison Square Garden (MSG). With the Garden facing a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) deadline toward the end of July, when the extension to its 2013 permit expires, a collision is inevitable. Yet the latest alignment of fixers could replace an unpopular scheme with one that is both infrastructurally desirable and politically possible.

The Narrative Changes, Again

The Penn Station situation has evolved rapidly since January 26, when a marathon event hosted by The Cooper Union offered several alternatives to the leading proposal at the time, the General Project Plan (GPP) associated with Governors Andrew Cuomo and Kathy Hochul, Empire State Development (ESD), and Vornado Realty Trust. That plan involved a combined station development and funding mechanism that included ten new commercial towers surrounding MSG and a neighborhood “blight” designation that opponents—particularly ReThinkPenn and the Penn Community Defense Fund, the event’s sponsors—viewed as spurious.

The event’s exchanges implied a Davids-versus-Goliath narrative that pitted community advocates and designers of bright, verdant, high-functioning civic spaces against private interests embodied by the Garden. MSG spans the tracks, its 261 supporting columns blocking redesigns that might improve circulation, admit daylight, and allow through-running rail service, which would convert the station from a terminal (where trains must reverse direction) to a more efficient station with two-way traffic. With an established preservationist narrative in full view but clumsily organized, one sensed that the public interest faced fierce headwinds.

A few weeks later, the winds changed. Vornado responded to the soft postpandemic commercial real estate market and high interest rates by putting the GPP on pause. This decision, combined with the impending July 24 expiration date for the special permit allowing MSG to continue current operations, opened a window for alternative plans. The three presented at The Cooper Union—PAU’s 2016 Penn Palimpsest, adapting MSG’s skeleton to create a new, light-filled hall; the Grand Penn open station/park complex proposed by Grand Penn Community Alliance; and ReThinkPenn’s reimagining of the 1910 design, envisioned by Atelier & Co.’s Richard Cameron, that would update its materials, technologies, and seismic underpinnings to meet today’s codes—all would require the “World’s Most Famous Arena” to move, seeking the fifth address in its 144-year existence.

MSG Entertainment (MSGE) CEO James Dolan has framed that condition as a nonstarter. A comment by Executive Vice President Joel Fisher at a Community Board 5 (CB5) meeting on February 22, however, admitting the Garden might consider moving within the neighborhood if a suitable plan appeared, gave proponents of more ambitious visions a hint that the powers in charge might channel their inner Daniel Burnham and embrace plans with the magic to stir rail travelers’ blood.

On April 13, CB5 added pressure toward a move by approving a resolution by its Land Use, Housing & Zoning committee to give MSG three years to “pursue a permanent sustainable solution, including relocation.” There may be limits, however, to how much sway the special-permit decision allows the public sector over MSG, which owns the land, the building, and the air rights. The permit is not a lease, as some have described it, but a zoning provision that allows events with over 2,500 attendees; few expect it to expire outright, which would wreck schedules for the Knicks and Rangers and concerts scheduled far in advance for the 20,000-seat space. Likelier outcomes stand to include resetting a time frame and imposing conditions but not kicking out the arena outright.

A “Mirror of a Mirror of a Ghost”

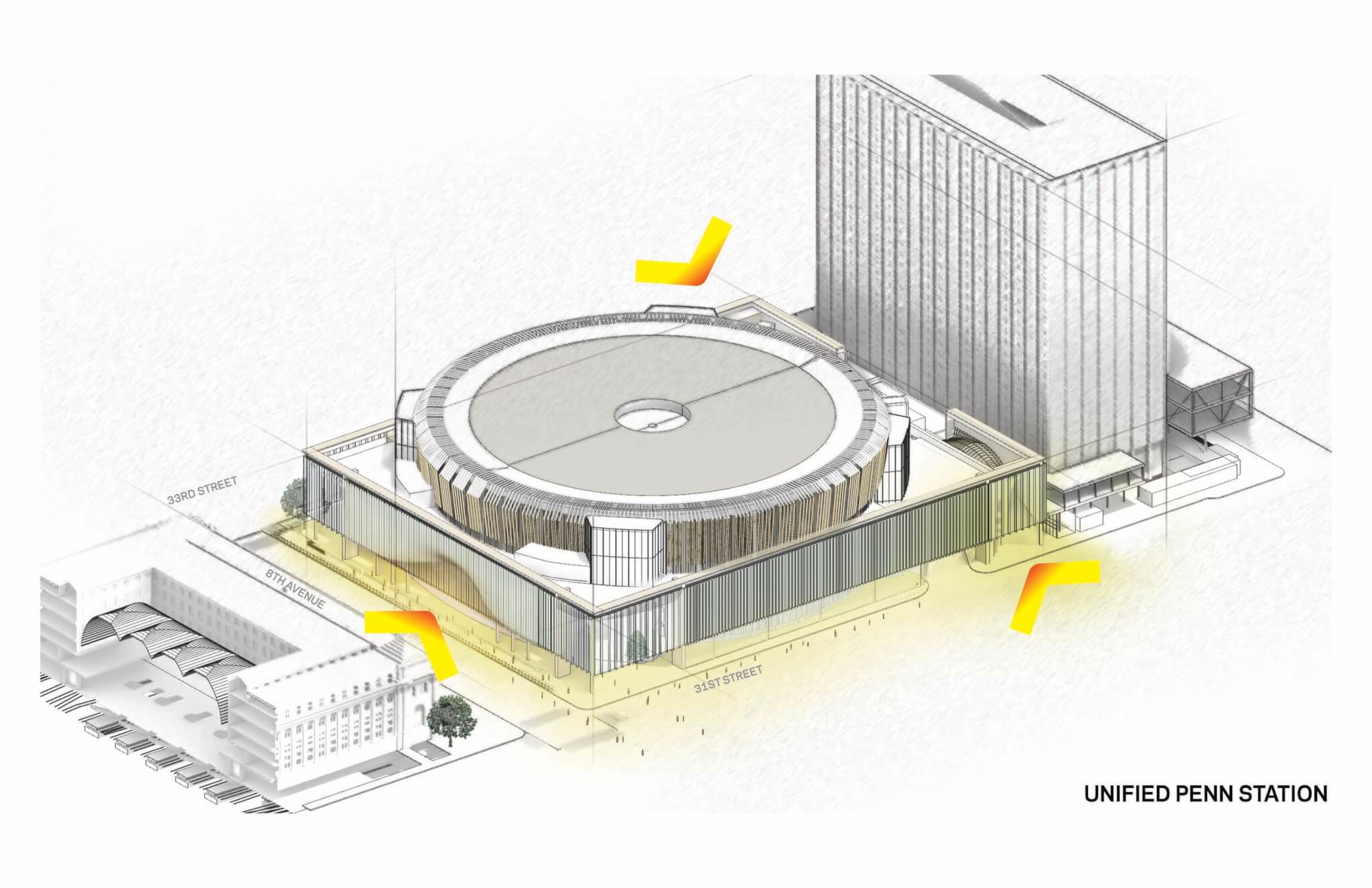

Further complications appeared with the latest entry by Italy’s ASTM Group and HOK, covered in The New York Times on March 28, which is supported by former Metropolitan Transportation Authority chairman and Port Authority executive director Patrick Foye and former U.S. Department of Transportation infrastructure adviser Peter Cipriano. This public-private plan would leave MSG in place, reclad it in aluminum and steel with a glass podium, wrap a new rectangular station around it, and replace the Theater at MSG (formerly Hulu Theater) with a new Eighth Avenue entrance. Further design and construction details will go public in June.

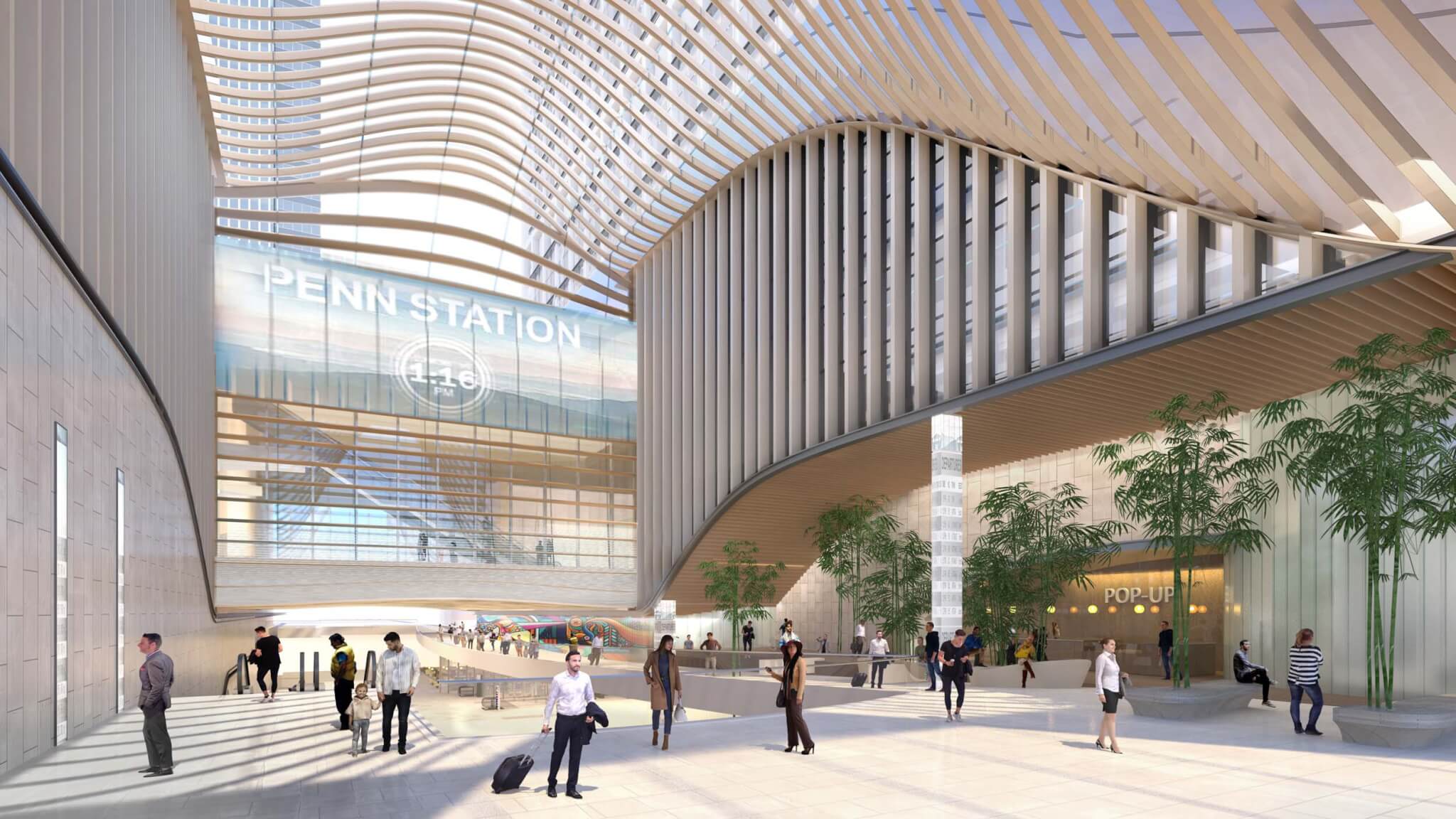

Though only three preliminary conceptual images were available by press time, ASTM Group/Halmar CEO Chris Larsen provided a statement: “Our team has developed a game-changing plan to fully deliver on Gov. Hochul’s new vision for a reimagined Penn Station that is iconic, spacious, accessible, and full of light and air, as well as improves the functionality for all users. We will continue to work closely with all stakeholders and community leaders to deliver a new Penn Station that uplifts the community and makes all New Yorkers proud while limiting risk to taxpayers through an innovative development approach.”

Another twist in the story arrived on April 17, when it was announced that PAU would join the ASTM-HOK team. PAU’s Vishaan Chakrabarti told AN that he was recently invited to view ASTM’s detailed plans. “What I didn’t expect,” he said, “is at the end of the meeting, the ASTM leadership invited me to join the team as a collaborating design architect.” After learning that ASTM and HOK had been working with various stakeholders for roughly a year, and finding their process “robust and deeply impressive,” he was “gobsmacked” and lost sleep over the offer.

Decades ago, Chakrabarti had worked on a plan to move MSG to the back of the Farley Building, and as recently as the January event at The Cooper Union he had been skeptical of other schemes that left the arena in place. It seems he found alignment between his values and those of ASTM, particularly the transit-function priority and the respect for Jane Jacobs’s four components of urban vitality: “density, mixed use, small blocks, and mixing old and new.”

In deciding to join the project, Chakrabarti said he “realized that it is better to light a candle than curse the darkness. I really feel that the team at PAU and I can make what is a very good project even better.” He continued: “It’s the most public plan I’ve seen that leaves the Garden in place.” It’s not surprising that Chakrabarti, who was director of City Planning’s Manhattan Office when Hudson Yards was rezoned in 2005 (and later joined SHoP Architects as its seventh partner prior to founding PAU), sees a public-private partnership as a way to save Penn Station; one challenge in keeping a new Penn Station from repeating the Hudson Yards experience, which combined large tax breaks and luxury condo development, will be for the ASTM team to separate public costs from privatized benefits and keep the two in balance.

In the initial press release for the merger, Chakrabarti said that the current scheme “promises a light-filled public transit hub similar to what PAU has always envisioned.” He pointed out that since ASTM and HOK have worked with MSG and Amtrak engineers as well as Vornado, the team is in a position to offer what PAU has advocated for years: “a comprehensive, full-block vision for how the public moves through that block on all sides of it, and whether there’s dignity to all of that movement; whether that dignity then spills over into a great neighborhood.”

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s plan, Chakrabarti added, “has a mid-block component, but it doesn’t have the Eighth Avenue component,” as it would leave the theater in place. ASTM’s scheme reimagines the midblock area and both long sides and continues Penn Station’s relationship to the Farley Building, across Eighth Avenue. “McKim designed the Farley Building to be a mirror of [Penn’s] original Eighth Avenue facade, so it’s a mirror of a ghost,” he said. “We are interested in how [one could] make a contemporary mirror of the Farley Building; it’s the mirror of a mirror of a ghost.”

Another strength Chakrabarti sees is that “this plan is not contingent on the GPP. So it does not rely on the demolition of all of those buildings, and it’s not looking for a funding stream from the GPP; it is an independently funded, self-contained entity within the superblock.” One potential avenue for funding is that ASTM, the world’s second largest toll-road operator, could finance the reconstruction of Penn Station through a model similar to that used in airports. The flows of public and private revenues are among the variables that will require public scrutiny when ASTM’s detailed plan emerges in June.

ASTM and HOK separate the question of station and superblock redesign from capacity expansion: A separate Penn South plan would replace Block 780 (between 30th and 31st Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues) and require cut-and-cover construction, disruptive displacements, and likely eminent-domain seizures. “One of the things that I like about the ASTM plan,” he said, “is it tries to solve one big piece of the problem here, independent of the issues of Block 780 and the GPP.”

In response to ASTM’s plan, an MSGE spokesperson noted: “As we’ve said, we are always open to discussions. As invested members of our community, we are deeply committed to improving Penn Station and the surrounding area, and we continue to collaborate closely with a wide range of stakeholders to advance this shared goal.” The spokesperson also offered a lightly revised statement, dated February 9, dismissing calls for a move as “misguided [and] completely unrealistic,” citing ESD’s estimate that moving would cost the public $8.5 billion and claiming that “no realistic proposal or financial model for moving The Garden has ever been presented,” including the 2007–2008 discussion of moving to the Farley Building before Moynihan Train Hall opened. The statement further argued that the special permit, extended for a decade in 2013 but required of no other local stadium or arena, should become permanent.

Willing to Be Convinced

The impasse could be temporary, say observers who have held that a station worthy of New York is attainable only after the Garden departs and that MSGE underappreciates its own incentives to do so. Chakrabarti is among those reconsidering that position. “I never believed that the only way to fix Penn Station is to move the Garden,” he said, “but what I’ve said is I have yet to see a plan that really fixes the station with the Garden in place…. If you can do all that without the Garden moving, it’s obviously a lot less complicated.” Now the ASTM-HOK-PAU team must address key challenges, including loading-access problems (existing service areas cannot accommodate large trucks, which often block sidewalk space) and the question of through-running, an efficiency upgrade recommended in various forms by ReThinkPenn and the Regional Plan Association (RPA), among others.

Putting transit ahead of components that have grown disproportionate in other projects, Chakrabarti says, is essential: Penn Station “is not a shopping mall; it’s not a casino; it’s not the base of an office building. It’s a train station, and it’s got to have a great public space around it, and if we do that the right way, it will pay for itself 100 times over.” Bringing American intercity rail up to global standards, he added, would also create climatic benefits such as reducing the need for short commercial air routes. Chakrabarti revealed that the detailed plan will also improve ADA access. “Between what happens in the midblock train hall between Two Penn and the Garden and the Eighth Avenue train hall, it will be a radically different experience and station. I think that will mean enormous things for this neighborhood.”

Instead of battles over MSGE’s intransigence, Chakrabarti continued, there could be “a moment of enlightened self-interest for the Garden, where if they prove that they’re going to be great citizens and cooperate, then some of the pressure the Garden gets publicly about some of these issues will dissipate.” Discovering that MSG personnel partnered with ASTM for over a year and that “no one in government had approached the Garden about moving whatsoever” catalyzed his realization that the immovable object might not move after all. “Design advocacy isn’t about getting 100 percent of what you want,” he summarized.

Tom Wright, president of the RPA, which has campaigned for major revisions to Penn Station since 2005 and called for its overhaul in the 2017 Fourth Regional Plan, has also had a change of heart about moving MSG, a shift due in part to a previous proposal by FXCollaborative and WSP for the MTA and Amtrak and in part to the ASTM-HOK plan. “For a long time, we were in the position that the Garden needed to move to make way for a great train station at Penn,” he said. “We’ve always known there are two parts of this puzzle: One is the renovation of the existing Penn Station, and the other piece will be the expansion of Penn Station. Those are working on parallel tracks and not necessarily on the same time frame right now. We’ve looked at this for years and believe that Amtrak and the MTA and New Jersey Transit will, through a separate process, conclude that they are going to need to expand Penn Station, most likely to the south, to create more tracks and platforms.”

Expansion to accommodate new trains from the Gateway tunnel will need to undergo National Environmental Policy Act review as well as negotiations with local residents, businesspeople, and advocates, who may find the project unacceptably disruptive. Block 780 presents complications, as Penn South plans may include two levels of tracks and platforms beneath it, Wright noted, “essentially condemning the entire block.” Planning for the community that must endure the renovation and expansion processes, Wright adds, is thus a third and indispensable aspect of the overall effort.

In the renovation component, FXCollaborative’s design convinced Wright and colleagues that a better station could be created by eliminating one of the floors within Penn Station and relocating Amtrak’s back-office operations without moving MSG. “It would allow you to widen the concourses and create higher headroom,” Wright said. “We started to believe that it showed that you could create a good Penn Station without moving the Garden. And quite frankly, if you can do it without moving the Garden, you should do it without moving the Garden, because moving the Garden is going to be extraordinarily expensive.”

ASTM’s plan improves on FXCollaborative’s, Wright added, by removing the theater and opening the Eighth Avenue side: It removes many (though not all) columns from platforms, expanding egress at notorious pinch points. Seventh Avenue access, widened concourses, and exits and entrances remain to be addressed when the full plan is released.

Extricating design and planning considerations from financial details has been a conceptual challenge for both insiders and the public. The ASTM plan is “now being talked about as an alternative to the GPP, when in fact these are different plans doing different things,” Wright said. The GPP represented New York State’s planning process (as opposed to a city rezoning) to determine where density should go and how to coordinate public and private-sector investments so that “the state would have the ability to benefit from some of the increased property values and use those revenue streams to help pay for the portion of the infrastructure that it needs to pay for.”

The general agreement on Gateway is that the federal government would pay for 50 percent of it, New York State would pay for 25 percent, and New Jersey would pay for 25 percent, according to Wright. The GPP mechanism would allow the state to recoup some of its multibillion-dollar Gateway commitment. “If the GPP goes away, New York State will have to come up with other revenue sources to pay for its piece of Gateway,” he said. Whatever happens with Vornado’s office towers or any other parcels, Wright added, must still undergo public review, including a Public Authorities Control Board vote. “The GPP gave nobody any as-of-right development.”

“I think the GPP should be put on a shelf,” Wright continued. The focus, he said, should return to other questions: “What do we want Penn Station to look like and how is it going to function and are we going to need to expand it and, if so, how does that work and how does that connect with the renovation of Penn Station? And once those issues have been brought forward and understood, then I think the public understands what it’s getting for the money, and then it’s a different conversation. But it still needs public approval.” ASTM’s proposal is “fully integrable” with these mechanisms, he added, and has benefited from proceeding collaboratively rather than “shooting in with a kind of a priori, deus ex machina plan.”

As for the other plans that propose relocating MSG, “there’s not much realism in those conversations” about the economics of the different components of the work required,” Wright offered. Among other obstacles, he added, “nobody working in Washington believes that there will be federal funding to contribute to moving Madison Square Garden.” Although ESD’s $8.5 billion figure may not hold up, Wright estimates that at least $5 billion in costs would be borne by New York State, “and that becomes competition for other infrastructure needs and funding. If the Garden was interested in moving and came up with a proposal with one of the other major real estate developers in the neighborhood and said, ‘This is something we want to do,’ then I think it would make sense for the city and the state and Amtrak and others to all engage with them and talk about that. But there’s been no indication whatsoever that they’re interested in that.”

An MSG move remains a must for many citizens for many reasons, including the illogic of a private entity having so much leverage over a public process and an essential public good; the ways the organization has treated its critics and legal opponents; the rankling vision of hardball obstructionism rewarded; and the tabula rasa that its move could create for broader expansion of public space. Beyond those objections also lie visions of a newer, better, more profitable MSG at a different site, a potential outcome that might eventually attract the company’s attention. (Knicks fans, in particular, may take note of how new quarters have sometimes breathed life into snakebitten sports franchises.) MSG’s opponents have even offered designs for offsite facilities.

With the clock ticking on the Garden’s permit extension, there stands to be complications on the path to solving Penn Station. For the present, however, the basic proposition, according to Chakrabarti, is: “If you accept the fact that MSG is not going to move, how do you make a great public station at Penn? What we’re working on now with ASTM and HOK is the way to address that problem.”

Bill Millard is a regular contributor to AN.