In his master’s thesis, Raymond Moriyama wrote: “The future of all Canadians is a rosy one, although one to challenge the wit and imagination of every planner.” The Canadian architect’s investigation into urban renewal was submitted to McGill University in 1957, seven years before work on his first major project, the Ontario Science Centre, began. Moriyama would later go on to co-found the Toronto firm Moriyama Teshima Architects.

Prior to designing the science center Moriyama was given the following brief: “Design an institution of international significance.” The institution opened in 1969, before WZMH Architects’ CN Tower, Frank Gehry’s expansion to the Art Gallery of Ontario, and Daniel Libeskind’s addition to the Royal Ontario Museum. The science center opened at a time when modernist architecture in Toronto was flourishing, coming only a few years after Viljo Revell’s New City Hall and a few years before the opening of Mathers & Haldenby Architects’ Robarts Library at the University of Toronto.

Last month, Ontario Premier Doug Ford floated plans to demolish the science center’s original building, and to open a new, smaller science center within the controversial Ontario Place development. Ford is suggesting housing development on the center’s current site, which is on 90 acres of land mostly owned by the Toronto Region and Conservation Authority (TRCA). The TRCA and the City of Toronto jointly leased the land to the science center for 99 years, expiring in 2064. In addition to the center, the site includes part of the Don River and adjacent ravines. The in-construction Ontario Line of Toronto’s metro system will terminate at the science center.

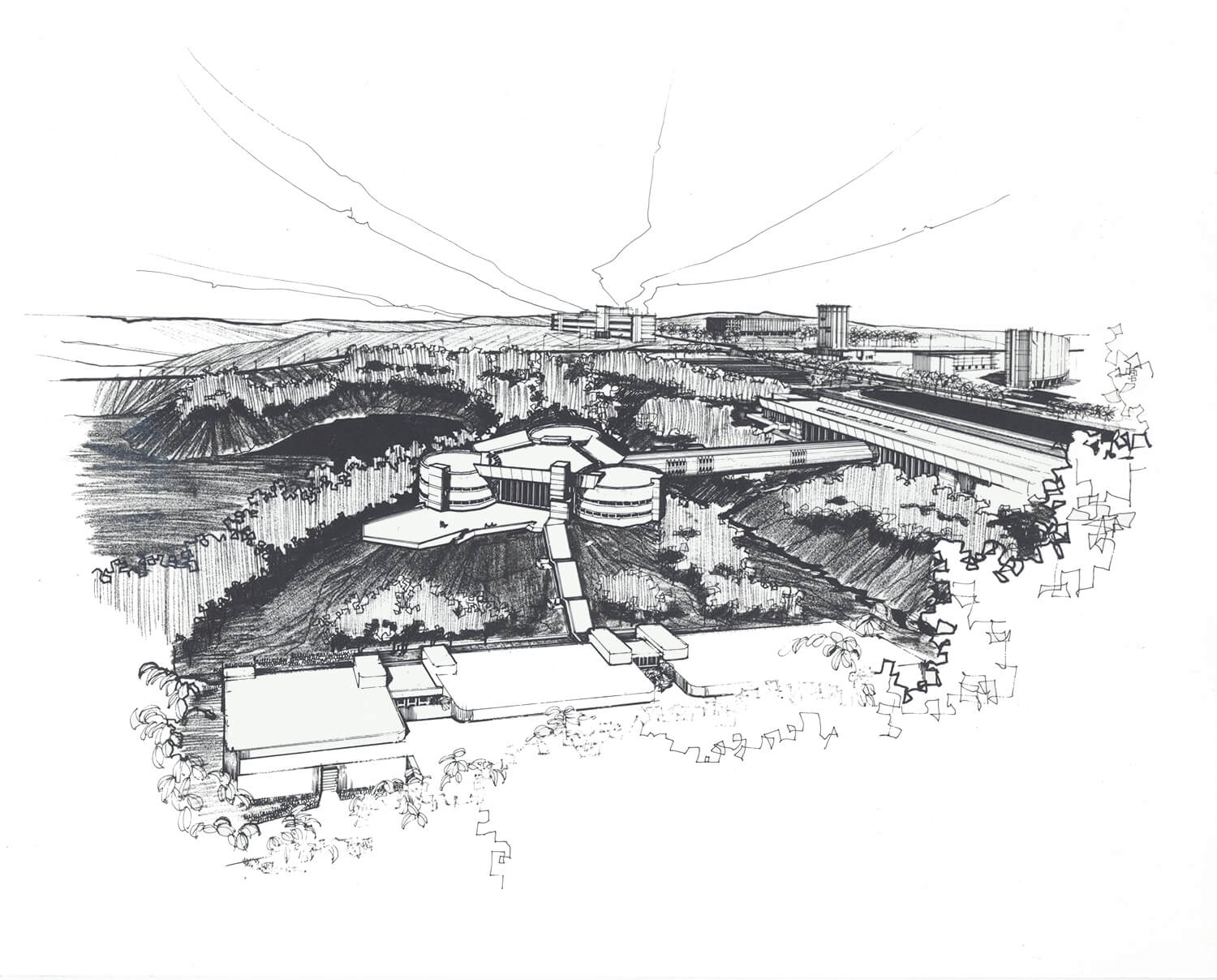

The TRCA said that they had not been consulted by the province or city regarding demolition plans, housing plans, and legal plans for canceling the lease. Specific to the science center, the TRCA owns: “The entirety of Ontario Science Centre lands beyond the front entrance building, which includes (from left to right) the bridge, additional portions of levels 1 and 2, and all of levels 3 to 6 of the Science Centre, which are located exclusively within the ravine.” They further clarified that existing municipal and provincial policies require that development take place outside of “hazardous” areas including the site’s deciduous forest and fauna.

In addition to the TRCA, backlash from the local community, architects, and politicians has been strong. Interim Liberal Party leader John Fraser told the CBC that the plans, including the Ontario Place proposition, “feel like it was done on the back of a napkin.” The development plan for Ontario Place, which was first announced in 2021, reimagines Toronto’s waterfront as a commercial and entertainment center with pockets of private development. Importantly, this includes a proposal for a waterpark, including a large parking garage, and a largely private spa.

Locating the science center within Ontario Place starkly opposes the institution’s original vision. In a statement, Moriyama Teshima Architects emphasized the importance of the science center at its current site: “The Ontario Science Centre is a landmark building, purposefully nestled into the natural ravine of the Don Valley, where it has succeeded in bringing that joyful study to the masses for over fifty years. The purpose of the Science Centre is inseparable from the site it currently inhabits.” The firm also highlighted the ever-important embodied carbon considerations of the project. The most sustainable building is almost always one that is already built, and demolished concrete, in addition to the carbon costs of constructing a new center with a massive parking garage, would be environmentally irresponsible.

Moriyama’s design also does, and should not, exist exactly as it finished in 1969. With the city itself changing, Moriyama & Teshima argue: “When Raymond Moriyama was designing the OSC he told the administration the programming should change every eight years—‘If it didn’t change, it would die.’” A regenerated Science Centre should continue its legacy of education, and can accommodate other uses such as community space, or even housing, if deemed appropriate. The Architectural Conservancy of Ontario also issued a statement, noting the importance of the science center in the local community, especially considering that Moriyama’s nearby Japanese Cultural Center (currently the Noor Cultural Center) is under threat from private developers.

Toronto’s mayoral by-election, which will select the candidate to finish out the term of mayor John Tory, is on June 26. The science center demolition and proposals for Ontario Place have become an important campaign issue, not to be lost in the city’s other growing pains, including years of rent increases that far outpace wage increases, cuts to the Toronto Transit Commission, and a reliance on private housing development that has failed to deliver for a significant swath of Toronto residents. While many advocacy groups remain vocal in opposition to moving the science center, pressure will be on the new mayor to stand the city’s ground (or not). How the final decisions are made over the science center redevelopment could show the abilities of Toronto’s activist groups and residents in shaping the future of their city.