Five years ago, studiorotan founder Renee Kemp-Rotan first visited Plateau Cemetery in Africatown, a settlement just outside Mobile, Alabama built by formerly enslaved Africans from modern day Benin after the Civil War. Its builders had been smuggled into the U.S. in 1860 on an 86-foot schooner called the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to dock on U.S. shores.

By 1920, Africatown had blossomed into a community of 10,000 people with over 2,000 homes, schools, places of worship, and a strong economy. But the prosperity didn’t last. Heavy industry in Mobile encroached on the settlement by the 1940s, engulfing the town in a sea of factories, while “economic conditions, exacerbated by Jim Crow–era housing, education, banking and transportation policies, slowly starved the community of its viability,” Gabriel Tynes, a local Mobile reporter with The Courthouse News Service, noted. Today, about 2,000 descendants of Africatown’s founders remain, yet they live scattered “amid vacant properties and blighted housing.”

At Plateau Cemetery in 2018, Kemp-Rotan told AN she couldn’t help but notice how its headstones featured names in both English and Benin languages. “I had never seen anything like it,” she said. “We as African-Americans have no idea as to what our African names were. But here I am seeing plaques that have two names on them, in English and African languages. That’s how it all started.”

Last year, as previously covered by AN, Kemp-Rotan launched the Africatown International Design Idea Competition, a brainchild of her firm in Birmingham, Alabama, to help tell Africatown’s remarkable story. The competition assembled a group of renowned Black architects, historians, archaeologists, and activists to convey Africatown’s history through architecture, storytelling, and community building. “For the longest time, the city of Mobile told Africatown descendants that the Clotilda was an urban legend, gaslighting basically,” Kemp-Rotan said. “These are important histories that have been revised and whitewashed for too long.”

This past Juneteenth, Kemp-Rotan, alongside Vickii Howell, CEO of M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast CDC, announced the competition winners who received cash prizes sponsored by the Better Place Foundation, a Birmingham philanthropic group; Visit Mobile, the city’s tourism organization; and AIA NOMA. Called “The Africatown Cultural Mile,” site programming was directly informed by Africatown community leaders. The competition brief prescribed four sites spread across the city of Mobile: Historic Africatown, the 44-acre former Josephine Allen public housing area, the “Africatown Connections Blueway” to be built with the National Park Service, and an Africatown USA State Park. “The Africatown descendant community basically gave me a list of things from our many civic engagement chats and the Africatown revitalization plan that they wanted to see at the four sites,” Kemp-Rotan said. “And that list is what we used in the competition’s design challenge brief, plain and simple.”

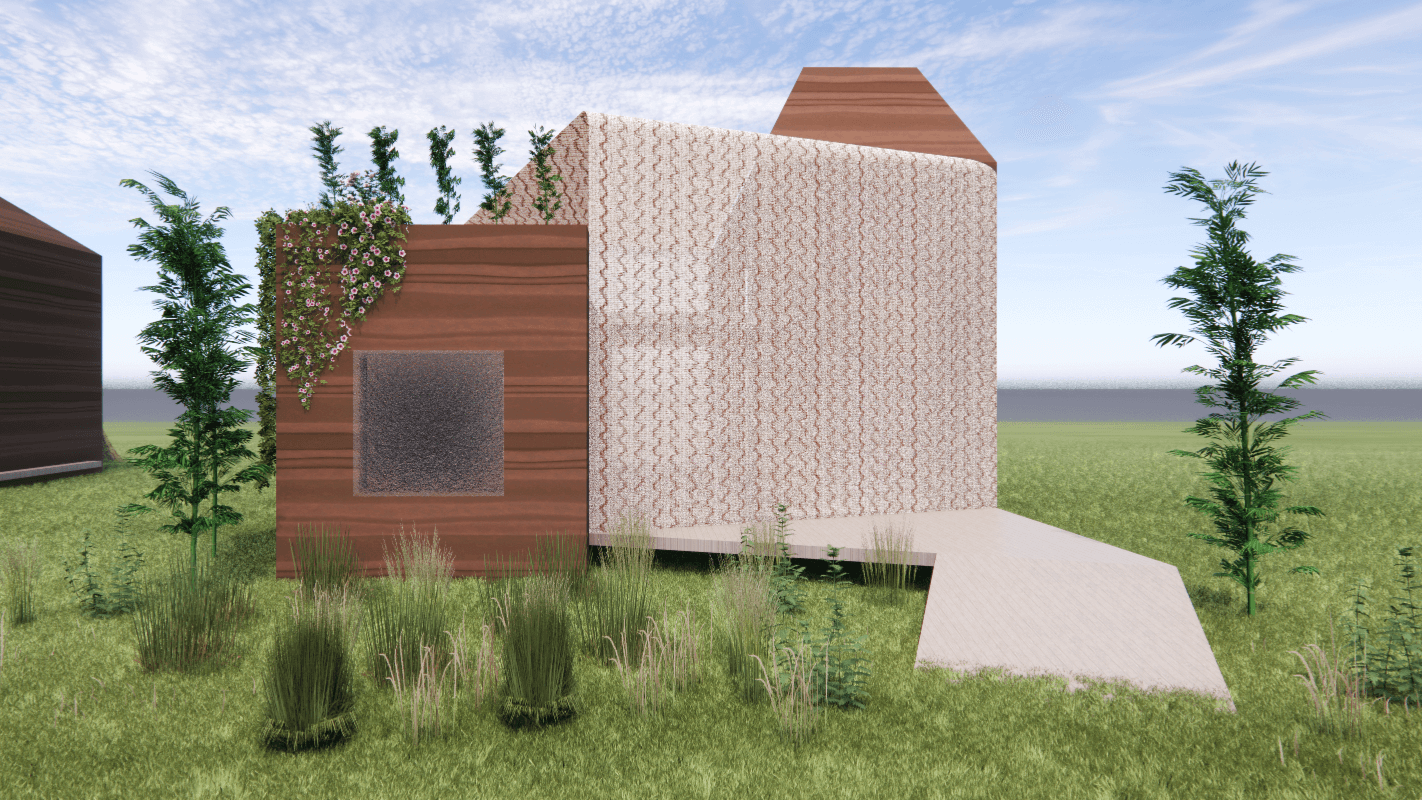

The Africatown Cultural Mile is envisioned as a network of cultural amenities from museums and performing arts venues, to a boathouse structure memorializing the Clotilda. The competition featured four first-place winners, one for each site. Site one in Historic Africatown’s winner was WXY led by Director of Global Practice Farida Abu-Bakare. Its runner-ups were Xu Han, Haiyi Sun, Zhe Qin, and Wei Tang in China; Kamau Kambui in Washington D.C.; and Johannesburg architect Peter Rich. Site two at the former Josephine Allen public housing area was won by Jerome Haferd/ BRANDT:HAFERD. Its runner-ups were Tianyuan Zheng, Ran Wang, Jiayue Yu, and Yajing Li; Moody Nolan; and Christian Coles, Olivia Harrell, Jada Ross, and Sally Murtadhi. At site three, Body Lawson Associates placed in first; followed by proposals from Dana McKinney, Megan Echols, and Jamel Williams; Moody Nolan; and Stephen Oliver, sole practitioner. And at site four, Turkey-based firm Fabl Design was awarded first prize; followed by Lagos architect Theo Lawson; James Wells; Nicole Hollant-Denise, AARIS Design Architects, and Evoke Studios.

Haferd’s winning entry focused on the Josephine Allen Houses, a former public housing complex that had been abandoned and was recently leveled. “My team was really drawn to that site because it allowed us to employ an architectural imaginary between land and water,” Haferd told AN. “Our proposal responded to the brief with an architectural vocabulary we felt matched the community’s imaginative ambition, connecting to Afrofuturism. The design uses a vocabulary we hope evokes Indigenous and ancestral architectures that also reads as something contemporary and futuristic.”

Director of Global Practice Farida Abu-Bakare led WXY’s winning entry for Historic Africatown. “I have never seen this level of collaboration within a community for a design competition,” Abu-Bakare told AN. “People from Africatown were very prescriptive and mindful about what they wanted to experience on all four sites. They offered a lot of resources in terms of books and media for us to learn about their community and culture. We used all of it as a basis for our design,” she said.

Given the context’s unique story, Kemp-Rotan had to rewrite the playbook for putting together a jury and design brief. “It’s absolutely unheard of to have [four] competition sites, let alone sixteen jurors,” she said. “Half of the jurors were designers, historians, and archaeologists while the other half were from the descendant and activist community,” she continued. “Then we invited eight more community observers to hear and speak to the jurors in debate to ensure that the competition was a truly democratic process.”

Jerome Haferd says that the design competition and broader activism surrounding Africatown could be a game changer for designers interested in working with descendant communities. “As a Black American architect and the direct descendant of enslaved peoples from that region of the South, I wanted this project to showcase Black excellence,” Haferd said. “I would say this competition and site has important and exciting ramifications for all American architecture in general, not just Black American architecture. The historical context that is being addressed here at this scale with this kind of site, including both the Black American and Native context, and how those stories are interwoven, are the reasons why this competition has incredible significance for the future of American cultural infrastructure, and how we think about American landscapes.”

Despite the competition’s remarkable success, only the future will tell if the ideas it generated will come to fruition. But Renee Kemp-Rotan is determined to help continue telling Africatown’s history. “Today, Africatown descendants have a chance to be truly in charge of telling their story through monuments, memorials, and interpretive sites that use Afrocentric architecture and the power of design to create an authentic world class cultural heritage destination dedicated to place making and place knowing,” Kemp-Rotan said. “The competition was programmed to elicit and promote culturally competent design ideas, and the whole world responded.”