Building Practice | Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller | Applied Research & Design | $35

As soon as you get a hold of Building Practice, a new book by Molly Hunker and Kyle Miller, it’s clear: building practice has been undergoing a reckoning. The tome’s introduction opens with a recap of how the profession was decimated by the 2008 global financial crisis, leaving many young practitioners with no choice but to leave the profession or invent obscure niches for themselves to better weather the storm. I can relate to that very well, as I was then part of the massive exodus from traditional building practice. Hundreds of thousands of architects in the United States alone left the field, most for good. But fifteen years on, a mountain of lessons has accumulated from the experience. Building Practice is a book about navigating crisis, a condition that has become pretty much permanent for so many trades. There are so many issues to deal with that a book like this had to be written sooner or later.

This compendium of personal stories shares both the frustrations and joys of running a contemporary architectural studio. Just shy of 400 pages, it dives deep, analyzing the nature of building practice by presenting dozens of case studies, so it would not be out of place to dwell on the reviewer’s own experience just a bit longer. My exit from working at a large commercial office led to assuming a role of an independent curator of architectural exhibitions, a change I could not quite foresee but a territory I was already familiar with. I embraced it wholeheartedly. Even so, it proved to be transitory. Today, after working for over a decade producing and curating exhibitions, it is no longer my primary focus either. The transition from one occupation to the next has turned into a condition that many professionals have by now learned to accept as a reality: change is the only constant.

It is this realization of the dramatic transformation of building practice and the architectural discipline overall that explains the authors’ alarming tone. The fragility of the whole situation is palpable right away, from the design of the book’s cover—the two-word title is depicted in a state of explosion with letters missing fragments, later found scattered across the front and back covers—to the oversized type of its 40-page introduction that lends gravitas to every word. There are many quotes inserted in there. One is by theorist Mark Linder who in his piece, “Transdisciplinary” pondered: “How, when, or where, does, did, or could architecture make its appearance other than as architecture?” With the help of the featured interviewees, the authors say an attempt was made “to define alternative forms of engaging with the marketplace and resituate architecture as a form of cultural production.”

The book’s content is a collection of conversations with architects, designers, curators, fabricators, installation artists, and critics who first became active around the time of the 2008 fiscal crisis, and who have spent the intervening years looking for new models of creating architecture in forms that are not only constituted in physical buildings. There is an assumption here that the crisis is a perpetual condition because the profession never went back to its pre-crisis mode of operation. Pre-2008, the culture revolved around celebrating the individual, the sole author or auteur. And issues that were beginning to be revealed then—environmental, ethical, social, and economic, to mention just a few—are still unresolved, even if global financial markets have long since rebounded (and numerous international practices grew exponentially in size).

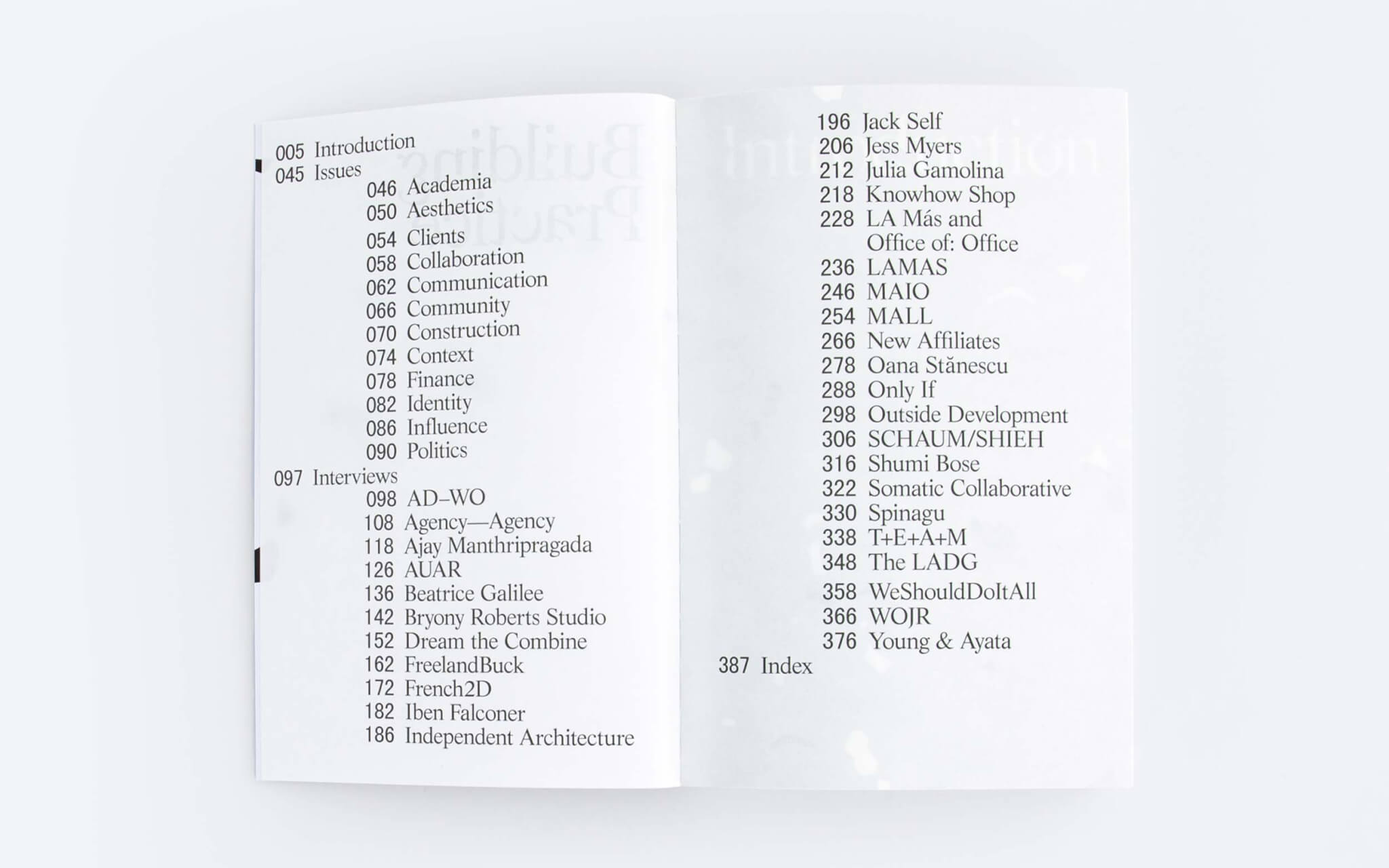

Once we are immersed in this context, the rest of the book is divided into two basic parts: A dozen issues from academia, aesthetics, and collaboration, identity, and politics are included, as well as 32 interviews. Vitruvius’s formula—commodity, firmness, and delight—was pushed aside. Instead, these conversations are framed by such questions as, “What does it mean to practice architecture?” and “What has been the most rewarding moment in your practice thus far?” The point here is to focus on what architecture can do, not just how it might look.

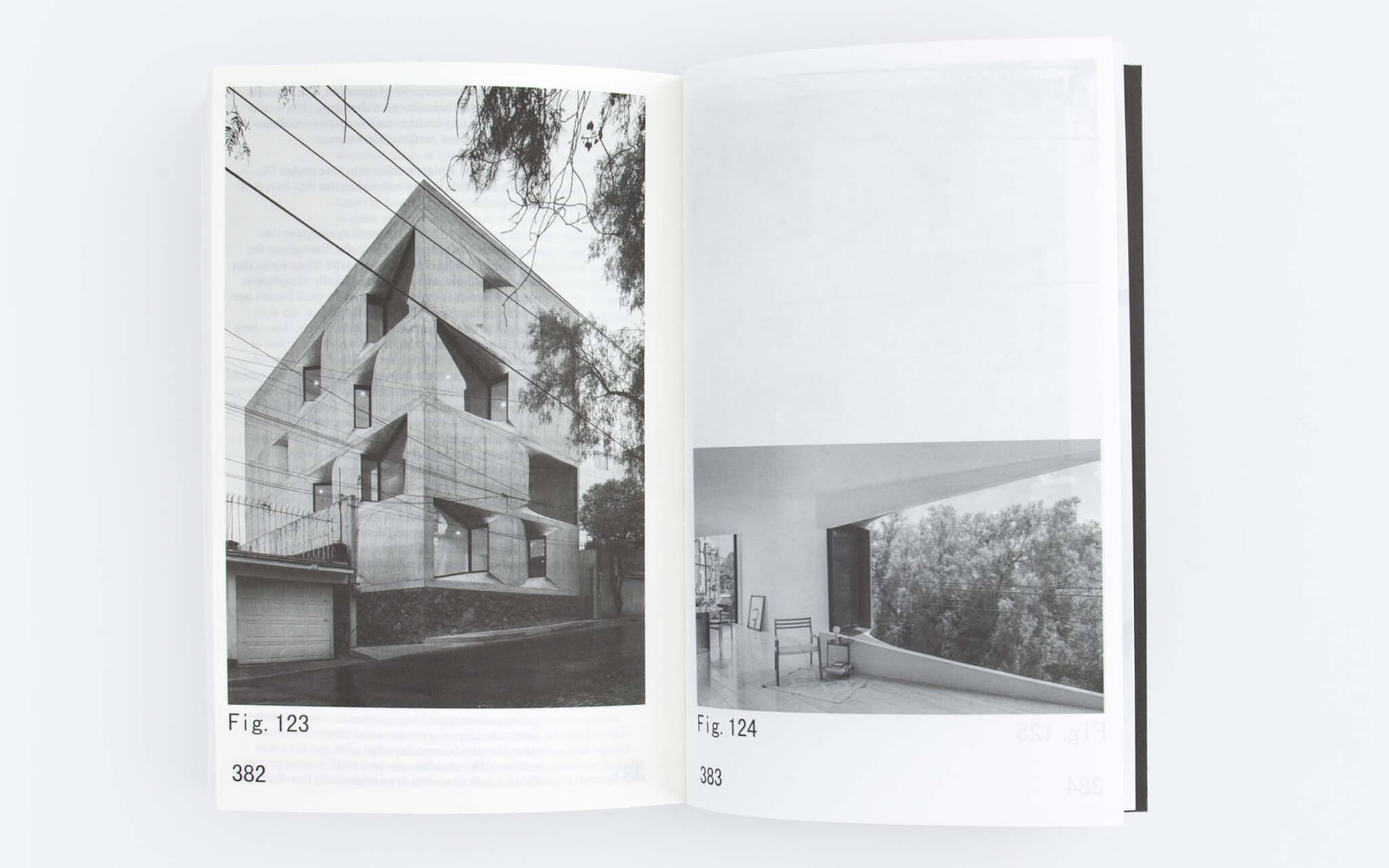

It is this angle that defined the list of invited protagonists. All represent architecture’s emerging generation, all are academically active, research-based, and grant recipients; nearly all are based in the U.S.; none are internationally celebrated. They enter the conversation one by one and anonymously, without a word of introduction. There are no portraits. Their contributions are title-less. The discussions revolve around the aforementioned issues, meaning their work is rarely addressed head-on, which is a striking departure from many project-centered and promotional books, panel events and talks that dominate architectural, social and intellectual life. The curated projects are all small-scale: They range from modestly-sized housing blocks to exhibitions, a window display, and even one tiny drinking fountain, which is particularly cute. There are just 12 semi abstract images in color, the rest are black-and-white. It’s clear that the center stage is given to the power of spoken word, new ideas and emerging discourse.

Three quotes, in particular, struck me as emblematic of the concerns expressed throughout the book. Elisa Iturbe, a cofounder of Outside Development, said, “One of the things that we in architecture always struggle with is the idea that a design is an imposition. But we were imagining that the architecture is actually something through which people can connect.”

Another statement by Jennifer Newsom of Dream The Combine puts into words a strong sentiment of how architects of her generation view their role: “We are more interested in the work being a platform for an energetic exchange between us and other people. We’re setting up a platform for things to happen.”

The final passage that I would like to cite here is directly critical of gratuitous practices of self-indulgent design: Anda French said, “We take the individual egos out of our conversations.”

Building Practice is a political work. It is a manifesto, if not a roadmap, on how to act. To be sure, there are many questions that lead to more questions, and the answers they generate are relevant, provocative, and open-ended. Nevertheless, the book strikes me as prescriptive, as it tells us what questions are “urgent.” They migrate from one conversation to the next, ultimately overpowering anything related to individual projects or inventive solutions. I am suspicious of this insistence on pointing to the architects in the “correct” way. I spent the last 20 years uncovering the individual and questioning what makes each author uniquely different from the rest. How do they dismantle conventions, build their own vocabulary, and propose new methodologies? I am therefore convinced that the point is not to show the way that’s right, but to show one more way. It is true and unscripted diversity that will lead to unlocking architecture’s potential most fully. In other words, as long as we are not certain what we are looking for, we are on the right path. Universality is not the answer.

Vladimir Belogolovsky is the founder of the New York City–based Curatorial Project and author of Imagine Buildings Floating Like Clouds.