“Once the first public housing development gets demolished, more will follow,” said Manuel Martinez, a New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) resident council president in Queens. Today, Martinez represents NYCHA residents from his community at the city level. Following an announcement made last June, Martinez told AN he’s “deeply concerned about the future of Section 9 and the instability households may have to face.”

On June 20, NYCHA revealed a $1.5 billion plan to tear down and replace buildings it owns in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, Fulton Houses and Elliott-Chelsea Houses. According to NYCHA, the proposal will raze 11 existing Section 9 towers, made up of 2,055 units, and construct new, perimeter-block buildings in their place containing 2,500 market rate units and 1,000 “income restricted” Section 8 units.

Section 9, which takes its name from the 1937 U.S. Housing Act, means the public housing authority owns the building; Section 8 means private entities (developers and banks) can own the building.

Today, about 5,000 people live in the Section 9 public housing developments; many of them are seniors. Elliott-Chelsea Houses (1,111 units) are between 25th and 27th Street, not far from Hudson Yards. Elliott Houses were completed in the 1940s and designed by the Swiss-American modernist William Lescaze. Chelsea Houses, built in 1964, were designed by Paul L. Wood. Fulton Houses (944 units) were finished a year later in 1965 by Brown & Guenther a few blocks south, between 16th and 19th Street.

Construction on the new Section 8 mixed-income developments would take place over the next six years. NYCHA press secretary Michael Horgan told AN that 94 percent of residents would remain in their existing apartments until construction on the new buildings is complete, while the remaining 6 percent would be “temporarily relocated within the campus or within the Chelsea neighborhood,” and still benefit from HUD/NYCHA rental subsidies. The architects of the project haven’t been announced.

Full Steam Ahead?

Today, NYCHA is New York’s largest landlord: It operates 177,569 apartments in 2,411 buildings throughout the city for 528,105 residents. It’s also the largest public housing authority in the United States. In 2021, NYCHA first announced that it would work with real estate groups Related Companies and Essence Development to carry out the aforementioned project in Chelsea. The idea was first floated in 2019 by the de Blasio administration, a proposal that was written off at the time as a “long-shot” and met with significant community opposition.

Related Companies, one of the developers behind Hudson Yards, financed that megadevelopment using an investor visa program, EB-5, meant to help “poverty stricken areas.” Its siphoning of $1.2 billion for Hudson Yards that was supposed to go toward public housing in Harlem amounted to what journalist Kriston Capps called “financial gerrymandering” in Bloomberg. Related Companies also led a project to demolish the Liberty Square public housing complex in Miami and build 781 units for low-income seniors in its place, receiving $106 million in tax credits along the way. This debacle was at the center of documentarian Katja Esson’s 2023 film Razing Liberty Square.

“Developers think they have the political backing to move forward with the new Mayor in office,” Marquis Jenkins, founder of Residents to Preserve Public Housing (RPPH), told AN. His New York City advocacy group tackles issues related to public housing in the city.

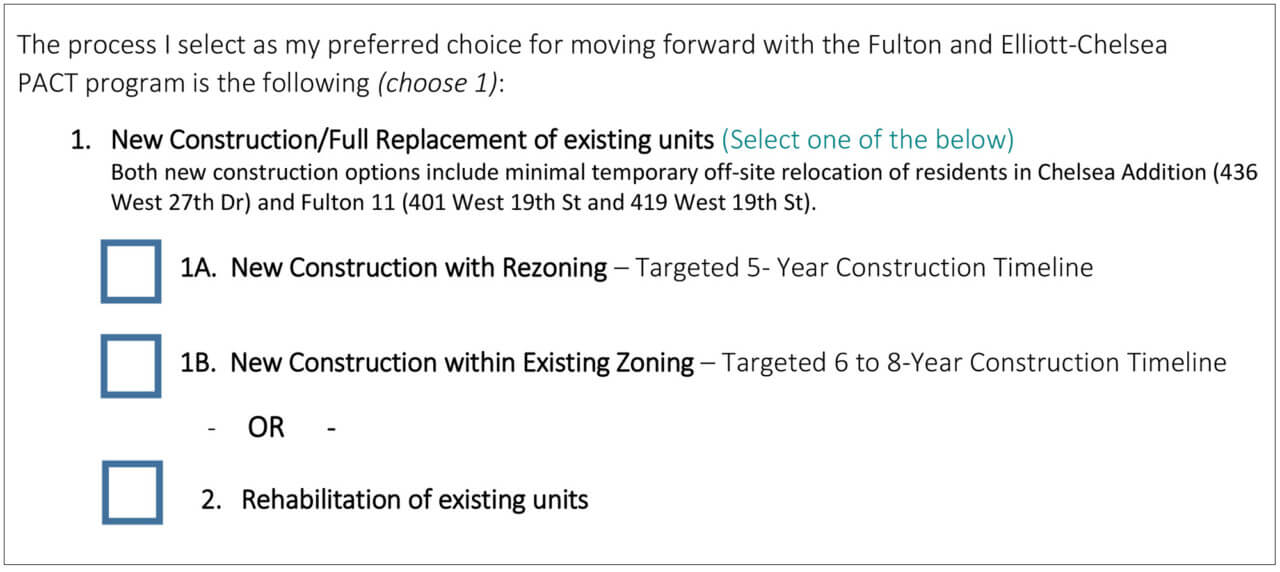

NYCHA representatives claim the Related/Essence plan to level Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses was approved by tenants following a survey polling their opinions about demolition. In turn, NYCHA officials said in a press release that “half of all respondents wish to pursue total redevelopment over rehabilitation of current buildings.” The New York Times shared that “30 percent of eligible residents, or roughly 950 people, responded to the survey, and about 60 percent of those opted for demolition.” Mayor Eric Adams praised the results, saying, “No one knows better than the residents what they and their neighbors need, and they were smart to recognize the potential benefits of completely rebuilding their campus.”

But new testimonies coming to light from tenants at Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses reveal that the project isn’t as cut-and-dry as it seems. According to Lucy Newman, staff attorney at the Legal Aid Society (LAS), “This plan is unequivocally not resident-led, and is guaranteed to uproot the lives of thousands of vulnerable New Yorkers.”

Resident Resistance

“There were three choices on the survey, but all three were for privatization. Even if everyone voted, we’d still get privatization,” said Celines Miranda, 48, who was born and raised in Elliott-Chelsea Houses. She opposes demolition. “In so many ways it’s an injustice. Only 30 percent of residents voted. So if you take into account residents as a whole, only 18 percent want demolition. They’re not taking into account the 70 percent of people who did not vote,” she told AN.

Miranda and many others feel that their homes in Elliott-Chelsea Houses—whose midcentury architecture she admires—as well as the community that’s grown there is worth preserving. She noted that many of her neighbors made a conscious decision not to vote because they didn’t trust the process or the developers. “I spoke to plenty of people who wanted these buildings preserved but they insisted on not voting. They refused to,” she said. “They knew something fishy was going on and followed their instincts. They knew that by voting they were giving permission for outsiders to come in and take over,” Miranda continued.

At the same time, Miranda questions Congress’s decision to “subsidize private developers” like Related’s billionaire founder, Stephen Ross, when that funding could be used to improve public housing. “We just need Congress to release their funds to Section 9 and not Section 8,” she said.

Meanwhile, resident association president Darlene Waters, who represents Elliott-Chelsea Houses, as well as Fulton Houses’ tenant association president Miguel Acevedo both support the demolition plan. At a Manhattan Community Board 4 (MCB4) meeting this July, NYCHA executive vice president for real estate development Jonathan Gouveia echoed Waters and Acevedo, emphasizing that the proposal was “resident driven.” But the LAS, who has worked with tenants in Chelsea since the de Blasio administration first announced demolition in 2019, asserts that “claims that the proposal is ‘resident-led’ are also misleading.”

Section 18 of the 1937 Housing Act is the legal mechanism which allows housing authorities to demolish their own holdings if deemed “beyond repair.” This would be only the fourth time Section 18 has been invoked in New York City.

“NYCHA is spreading this message that if a tenant association president approves demolition under Section 18, then the tenants also support it,” said Ramona Ferreyra, founder of Save Section 9 (SS9), a tenants’ rights group. “But just because a tenant’s association president says he supports demolition doesn’t mean the tenants do,” Ferreyra shared with AN.

Today, it seems that “a lot of people don’t know what they voted into,” Miranda said. Echoing Miranda, Jenkins confirmed that the “survey itself didn’t even mention the word ‘demolition’ which made it confusing for people.” Combined, both buildings total about 5,000 residents, of which just under 1,000 voted. Additionally, Jenkins notes that most of these responses came from Fulton Houses, a turnout that further skewed the tally.

Unpacking the Survey

The LAS said that “numerous reports from residents about the survey process stated that the information provided to them was opaque and inaccessible, obscuring the fact that two of the survey options required complete demolition, and were totally silent on the development of 2,500 market-rate units.”

For Miranda, the process by which the survey was conducted was “secretive.” She notes that the last day of voting was on May 20. Afterward, Miranda and her neighbors anxiously contacted Essence Development for the results. But they didn’t learn the demolition plan had been approved until it was announced on the local evening news on June 20, one month later. “News spread like wildfire among us residents,” Miranda said. “We got the results from the news before Essence and Related announced them to us. Next day they posted a notice on our doorknobs.”

Despite overwhelming confusion related to the survey, NYCHA has said it was written with the intention to be non-biased and clear. In an email exchange with AN, NYCHA’s Michael Horgan said the survey was developed by resident leaders at Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea, NYCHA, and Citizens Housing and Planning Council (CHPC), a nonprofit with expertise in community engagement.

At this July’s MCB4 meeting, NYCHA’s Jonathan Gouveia said the survey was “designed with resident leaders, Essence, NYCHA, and CHPC,” a statement which other resident leaders and LAS have called into question. CHPC Deputy Director Sarah Watson clarified in a statement to AN that “CHPC’s role was to verify and tabulate the survey responses,” and Horgan only later submitted to AN a change to his previous written response, stating that “CHPC was not a part of the survey development process, as previously indicated.”

Regardless, amid the public outcry, NYCHA officials have defended the survey—which it touts as a first-of-its-kind selection process. “We developed our engagement process in full partnership with the two tenant association presidents and their respective leadership teams. Residents have been involved in every step of this process,” Horgan told AN.

Location, Location, Location

Today, many New Yorkers have suspicions about why these eleven towers in Chelsea were specifically chosen for NYCHA’s demolition pilot program over the others it operates across the five boroughs. But for those keen on the city’s inner workings, the answer appears obvious. “The first three rules of real estate are location, location, location,” said Martinez. “Just look at where NYCHA wants to tear down buildings!”

Properties at Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses sit next to some of the most expensive real estate in the world. Across the street from Elliott-Chelsea is the Avenues School, the most expensive private elementary school in New York City where a handful of A-list celebrities send their children. Just a block west sits the High Line and the long stretch of ultra-luxury buildings that line its edges. If privatized, the land below Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses could yield billions of dollars.

“There are developments that are in worse condition. They’re not talking about doing this in the Bronx yet because the land isn’t nearly as valuable,” Jenkins said. “But the current plan sets a dangerous precedent for developers to do this in neighborhoods across New York.”

After decades of turmoil, the level of trust between tenants, NYCHA, and developers is low. Ferreyra referenced the story of Cabrini Green in Chicago, a public housing complex torn down in 2000 following long bouts of neglect and structural disinvestment. When demolition was announced, Cabrini Green residents were issued a “right of return” letter and told they would have new homes in a few years, just like residents of Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses are being told today. But twenty years later, the majority of displaced Cabrini Green tenants are still waiting.

No Alternative?

With a publicly announced deficit of $78 billion needed for rehabbing properties, it’s obvious that NYCHA is in crisis, and NYCHA residents across the five boroughs have felt the effects of deferred maintenance. Is privatization vis-a-vis demolition the best way to provide better housing for NYCHA residents?

Many don’t think so. SS9 has called for a “forensic audit” of NYCHA by the end of the 2023 fiscal year, at the same time spelling out clear strategies that can be employed to fix public housing without privatization. SS9 also called for a moratorium on the construction of “anything that is not Section 9.” Another proposal includes reinstating “federal and tenant oversight of public housing authorities.”

It seems that NYCHA is more interested in distancing itself from the duties of a landlord and instead unloading that burden onto the highest bidder, no matter how nefarious its track record appears.

This unloading signals to many a “failure” of public housing in New York City, where the controversial effects of public-private partnerships have already been tirelessly fought and witnessed from Penn Station to Hudson Yards. But, as was the case at Pruitt-Igoe, a once thriving public housing complex in St. Louis torn down in 1972, it’s essential to note that the “failure” of Section 9 public housing in the United States is regularly a calculated decision by the government and developers and certainly not an inevitable, natural occurrence.

The pain and distrust felt by New Yorkers like Manuel Martinez is palpable: “NYCHA has been the main obstruction to the success of Section 9 public housing in New York,” he said. “They’re acting as if Section 9 is dead while they’re the ones killing it.”