The original version of this essay “How Framing Works” appears in American Framing: The Same Something for Everyone, published by Park Books.

Real estate has a different purpose than architecture: it exists to satisfy the requirements of the owner (and sometimes user), and more importantly, it is a place to park money. If you’re going to buy something to park money in, then you do so needing to know that you will at some point find a buyer so you can withdraw your money (ideally with ridiculous profit). Once you decide that your interests in architecture include the ability to withdraw your money from it, then all your concerns about architecture as a practical art and how it works (or looks) are conceded to this future buyer; you’re living in someone else’s house. Since your future buyer is only imaginary until the future, then it follows that all those other aspects you might be concerned with have to be the least problematic or unattractive (in every sense) to the most possible people so that your future buyer might actually exist.

In the essay “Toward a Critique of Architectural Ideology” (1969), Manfredo Tafuri identifies the plan as the organizer of space, which orders society, and as a result produces the ideological purpose for the entire enterprise of architecture. The essay traces the migration from the plan as the project of the architect (and therefore architecture) to the plan as the project of the city. Up until recently, he argues, the city developed largely planless, and as a result the city (and therefore society) was conditioned by architecture, whereas in the modern capitalist endeavor, the city (and its plan) began to move architecture from its position as an ideological subject into a materialist object, effectively neutering the political force that architecture (through the plan) could provide. In this evacuation of architectural purpose toward society, and the role of the avant-gardes in hastening the organization of the plan into the plan of capitalist development, Tafuri finds reason to accuse architecture of accepting its commodification and relinquishing its responsibilities as a subject (and being operative). This new role of architecture and the architect produced an anxiety that was resolved through a change in the priorities of architecture, privileging the function of delight and novelty. Architecture, which once conditioned the city, became conditioned by the city, and because the city was no longer the planless accumulation of architectural subjects but now ordered by the plan of development (and capital), architecture serves only to create novelty.

This is the existence of architecture as an object and not a subject, of architecture as real estate. The misconception is that this situation pushes architectural choices to only the blandest, the most “beige”—an idea that presumes architecture to be a practice of finishes. In practice this desire to be able to sell produces both blandness and novelty (to be bland enough not to offend imaginary future buyers, or novel enough to delight imaginary future buyers). Which is to say it now primarily appeals to taste in one way or the other. The trouble with taste is that it appeals to class, and further subjects architecture to being conditioned by the city, rather than conditioning it.

Architecture as an object can be anything or nothing and look like whatever it wants (eccentric or ordinary) as long as it’s not difficult. Being difficult requires people to make more complicated choices, and to reexamine priorities, expectations, and assumptions about the world. This (difficulty) was the political power of architecture before capitalism, and has become problematic as a quality of architecture during capitalism. Its purpose, to appeal to the tastes of imaginary future buyers, can handle a full spectrum of superficialities, but has absolutely no room for upsetting priors in any deep way. Architecture as an object needs to be liked or disliked. This simple relationship is a solid requirement for consumer products, of which architecture is now one. Difficulty in architecture produces a deep anxiety that the imaginary future buyer will always be just that, never materializing, and never allowing one to withdraw money from architecture real estate.

If you want an architecture that feels more meaningful than its utility as a place to park money, then it’s worth considering an alternative to the exploration of architectural eccentricity and ordinariness. If both approaches produce genres of architecture entirely susceptible (and more likely, that lend themselves) to being commodified, an alternative would be something that has the ability to more deeply affect, or disturb, expectations about a building, a form of architecture that challenges assumptions about use or appropriateness. Ignoring those demands might make space for vernacular and idiosyncratic work, as a kind of veto on the development plan of the city. The trap to be avoided is trafficking in architectural style, or believing that architecture is about style at all, instead of working with plan, and instead exploring a more forceful and less controllable form of creativity where, rather than eventually domesticating the exotic through normalizing and commodifying what is eccentric, or trading in the well-known through maintaining normalcy, the normal is made weird.

In order to do this, architecture might be thought of less as a thing (or an object) that’s produced, and more as a form of creativity that examines space for an individual or groups of individuals, requiring more idiosyncrasy, more intuitions and personal preferences, and weirder propositions about how one might organize social space and private space, producing as a result an architecture that is inherently more difficult to understand, less accommodating to assumptions, and more challenging to the cities it resides in; becoming, again, a subject in the world, and not an object of it. Difficulty in architecture, or difficult architecture, isn’t the same thing as illegibility in architecture or illegible architecture (although sometimes it is illegible). To produce difficult work is to create something that questions existing assumptions about utility, use, appropriateness, politeness, societal morals, concepts of being neighborly, protection of the individual or exposure of the public, what people are asked to do with their time, the nature of labor and the origins of the materials, mythologies of privacy, the politics of domesticity, or the true nature of work and employment, among other things.

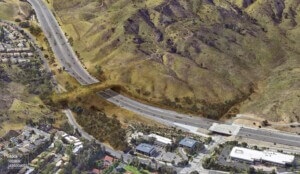

If the architecture of capitalism requires smoothness and virtuoso complexity and tasteful anonymity and efficiency and thoughtful planning, resulting in something you can like, the characteristics of a difficult architecture should stand in the way of those qualities: it should be rough, dumb, outside taste, clumsy, resulting in confusion. America in the early nineteenth century was undergoing a rapid expansion in both population (from immigration and births) and land (from a belief in Manifest Destiny), and needed a form of architecture not reliant on the European methods of building the colonialists brought over: masonry, heavy timber, etc. The logistics of population growth and settler occupation made traditional methods requiring skilled labor and slow work impractical. Softwood framing originated as a kind of outside solution, one that came about through the simultaneous existence of plentiful and cheap wood ignored by carpenters and timber builders, small, light, and portable pieces of lumber, and cheap nails that could connect framing elements without skillful joinery. Where slow-growth, heavy timber is capable of carrying significant loads through massive beams and columns, softwood framing just calls for more weak wood, multiplying columns to make any individual column meaningless and creating something that has neither the structural clarity of a timber column nor the brute force of the masonry wall: the stud wall. The mobility of the 2×4 and ease of wood-frame construction allowed new people to produce architecture, and as a result, to produce space. At roughly the same time that architecture launched the search for novelty as the new pursuit of the architect, wood framing came along to allow architecture by non-architects, kept immune from the pressures of practice by simply not practicing, more interested in the idiosyncrasies of their own quotidian needs. This de-skilled labor initiated an architecture that eventually came to constitute over 90 percent of built housing in the United States. It’s this fundamental sameness that paradoxically underlies the American culture of individuality, unifying all superficial differences, organizing the irrelevant differences in finish that identify tastes. In this way, framing suggests an alternative to the narcissism of architecture open to its own commodification.

At the same time, framing introduces an improvisational creativity seemingly open to all other forms of creative practice, but generally unavailable to architecture. After all, architecture is planned, then drawn, then organized for construction, then built. There’s no ability to move a wall on-site when building with prefabricated steel or engineered reinforced concrete. Framing doesn’t require the same uptight approach to architecture. Lumber arrives on-site and is cut in place to do whatever. It’s easy. Windows and doors can be introduced and removed at will. Walls can be moved or removed with little consequence, or consequences that a few more articles of lumber can resolve in no time. Wood framing allows for immediate and intuitive changes, accommodating desires unknown until realization. Framing is the closest architecture to action painting. The ability to change direction during construction without much effect on delivery time or cost allows for a medium of space that is vastly more mutable, wily, un-precious, and open to idiosyncratic experimentation that satisfies specific individual desires and curiosities. Framing allows architecture to be irrational, risky, and ugly, to make mistakes, creating space that stands in contrast to the industrialization of culture. It’s this constant uncertainty and allowance during its production, its existential impermanence, that develops a space for creativity and architecture that resists the trend toward taste and solidity.

Subversion can occur where the economic stakes of experimentation are so low that personal, anti-market desires and the unfashionable can be materialized, and normal things altered toward idiosyncrasy. Pressures from the development plan moved architecture to pursue expensive novelty or ordinary tastefulness in order to appeal to the imagined desires of future owners, trading away the future. Framing gets around this pressure through allowing for an architecture that can be impulsive and at times even gross—the result of ad hoc choices—without the consequences (change it again!). This introduces a liberatory creative freedom to architecture traditionally only found in other (cheaper and more immediate) forms of artistic practice. The typical costs of architecture (labor, material, land, time) continually work against architecture’s ability to explore impulse, and instead condition it to be deeply considered and planned. Framing works through crudeness; it’s easy, it’s cheap, everyone can learn it, and anyone can do it. Framing works by allowing for participation at every level and offering a way to act out architecturally, indulging instinct, accommodating ideas, and seeing where things land.

Paul Preissner is an architect and principal of Paul Preissner Architects. He is professor of architecture at the University of Illinois Chicago and the author of Kind of Boring.