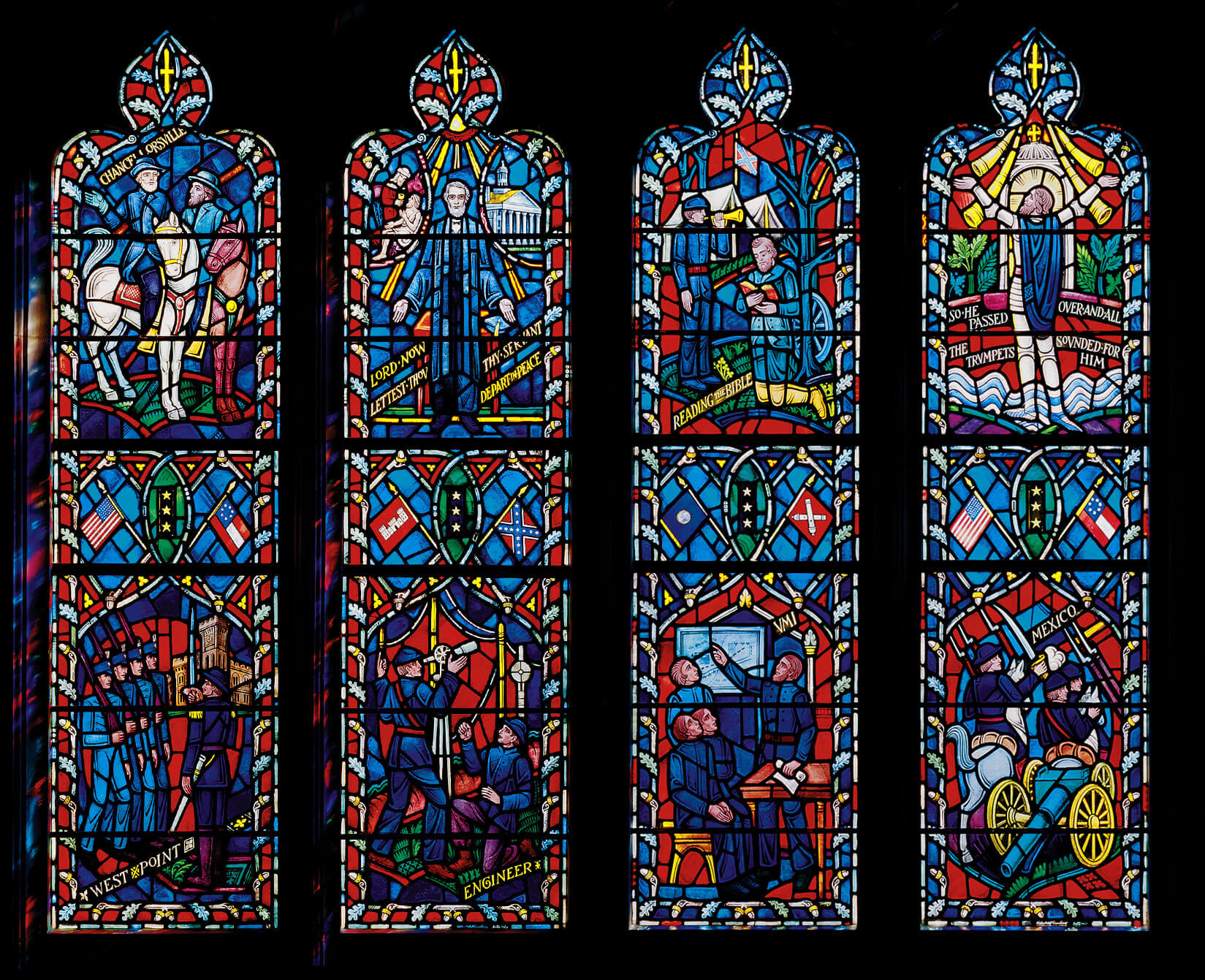

What does it say about the United States that, until 2017, stained glass portraits of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson adorned Washington National Cathedral—one of the country’s largest places of worship located in the nation’s capital? It’s true: Since 1953, effigies of Lee and Jackson occupied the nave of Washington National Cathedral in a niche not far from where Woodrow Wilson is buried called Memorial Bay: a 9-foot by 14-foot by 20-foot void near the entrance with a marble floor and vaulted ceiling.

This changed, finally, last weekend when the windows were replaced with new ones by Kerry James Marshall that tell the story of civil rights movements in the U.S. On September 23, Marshall joined Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, historian Henry Louis Gates Jr., California representative Sydney Kamalager-Dove, and Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, and others, at a grand ceremony to inaugurate the new art work entitled Now and Forever.

The opening was christened by a poetry reading from world renowned poet Dr. Elizabeth Alexander. Alexander debuted a never-before-heard poem “American Song” that will be engraved on stone tablets underneath Marshall’s windows. Like the artwork by Marshall, Alexander’s art celebrates African-American contributions to the U.S. while confronting its white supremacist past.

At the opening, Reverend Randolph Marshall Hollerith, dean of Washington National Cathedral, said the previous windows were “offensive, and they were a barrier to the ministry of this cathedral, and they were antithetical to our call to be a House of Prayer for All People. They told a false narrative, extolling two individuals who fought to keep the institution of slavery alive in this country. They were intended to elevate the Confederacy, and they completely ignored the millions of Black Americans who have fought so hard and struggled so long to claim their birthright as equal citizens.”

The idea for Memorial Bay at Washington National Cathedral came out of Jim Crow. In 1931, a Mrs. Oscar Barthold, a relative of a Confederate soldier, first floated the idea. Later in 1952, a northerner James Sheldon agreed to bankroll the portraits to “unite the north and south.” The United Daughters of the Confederacy—a white supremacist group based in Nashville, Tennessee—donated the effigies of Lee and Jackson to the church in 1953 where they remained until 2017.

After the mass shooting which left nine African-Americans dead by a white supremacist at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, Reverend Randolph Marshall Hollerith made the decision to have the Confederate windows removed. The Confederate windows were subsequently placed into an exhibition Make Good the Promises: Reconstruction and Its Legacies at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In 2021, Marshall was tapped to replace the Confederate hate symbols with original art work. Marshall’s portraits imbue the civil rights struggle with iconography from the Bible. Marshall, whose paintings often sell for millions, charged only $18.65 for his commission, marking the year African-Americans were freed from slavery. In his piece, Marshall equates “the fall of humanity” with the creation of America and makes it clear that the struggle to end racism and white supremacy here continues to this day.

“The church in general, across all faiths and this National Cathedral in particular, exists as a symbolic representation of humankind’s aspirations toward perfection, and a desire to keep the promise of redemption when we offend and fall short of the impossible,” Marshall said at the dedication. “Even the God of the Cathedral didn’t have a permanent remedy against the evils that humans seem destined to inflict on one another. Today’s event has been organized to highlight one instance where a change of symbolism is meant to repair a breach of America’s creation promise of liberty and justice for all, and to reinforce those ideals and aspirations embodied in the Cathedral’s structure and its mission to remind us that we can be better, and do better, than we did yesterday, today.

“I want to be clear that this is not the end of the end of the Cathedral’ s journey; rather, today is an opportunity to recommit ourselves, and to recommit this Cathedral, to join that march toward fairness for all Americans, but especially for African Americans,” added Reverend Randolph Marshall Hollerith. “There is a lot of work yet to be done to confront systemic racism, to foster racial reconciliation and to be repairers of the breach, both in the past, the present and in our future.”

Over the next nine months, the poetic words from “American Song” by Dr. Alexander will be inscribed into stone and eventually set in place under Marshall’s windows. The original Lee and Jackson windows will return to the Washington National Cathedral’s basement for perpetuity.