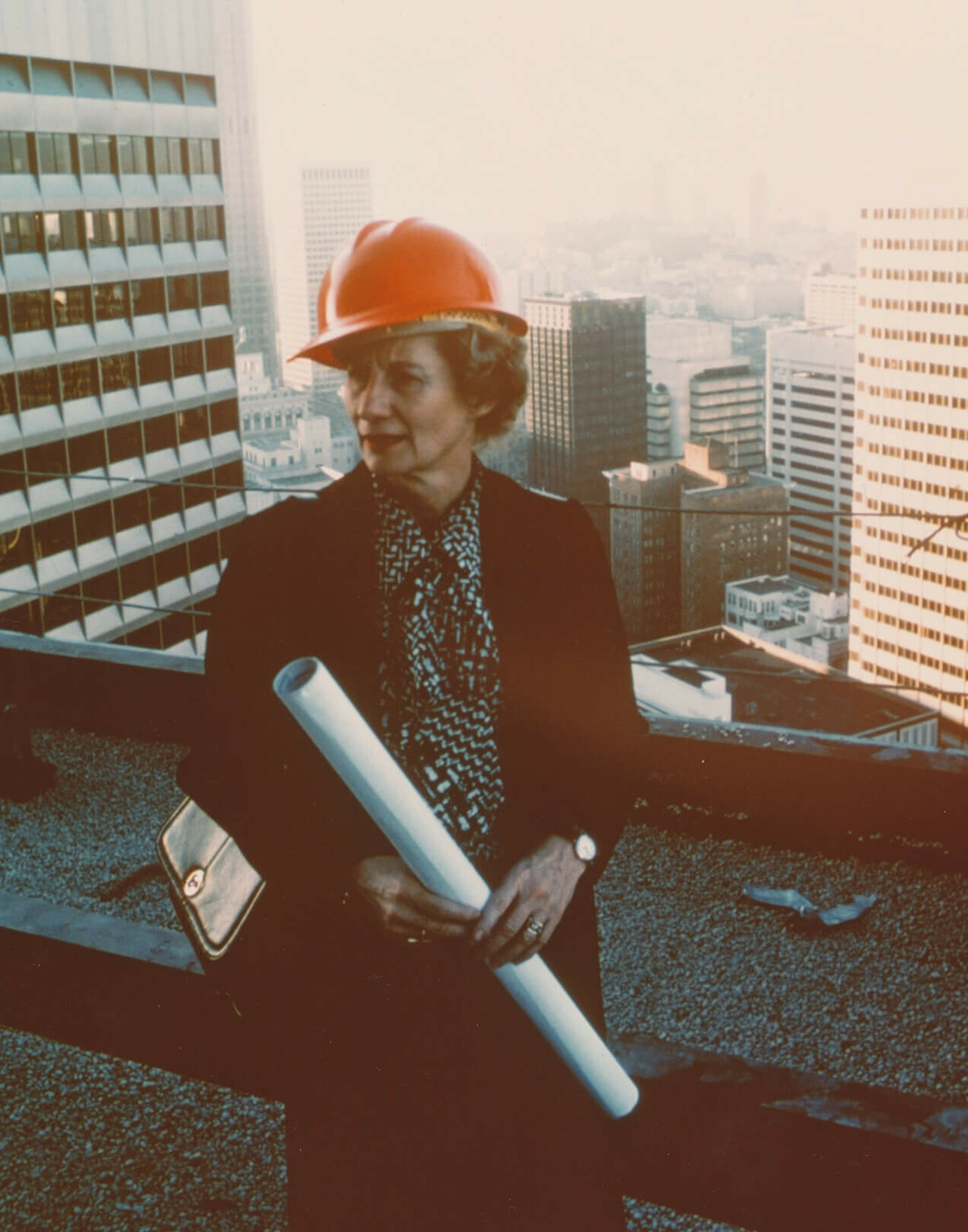

Beverly Willis—the San Francisco– and New York–based architect, and pioneering advocate for women in architecture—died on October 1 at the age of 95 at her home in Branford, Connecticut. News of her passing was confirmed by her spouse Wanda Bubriski. Her death was from complications related to Parkinson’s disease.

“We share with deep sadness the passing of our dear founder, Beverly Willis FAIA, a titan in many fields, who showed us, among other lessons, that women can have many careers as they grow and find their true voices,” said Cynthia Phifer Kracauer, executive director of the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation. “Bev always wanted to be remembered for her work as an architect, but she didn’t stop there: She became a real estate developer, an artist, author, film director, producer and an impresario of intellectual activity creating institutes of study including BWAF, Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, her most recent venture, which emerged first as a means for scholarly recognition of women in the building industry, but which became a vehicle for creating a more inclusive and equitable culture in those professions. She truly did encourage and inspire other women throughout her life, stiffening their backbones and opening a new chapter for their achievement,” she told AN.

To date, Willis is remembered by Kracauer, and many more, as a trailblazer who opened doors and shattered glass ceilings.

“Women continue to shape Manhattan, above and below ground, along its waterways, through its parks, and in designing the cities vast array of buildings,” Willis said in her 2018 film, Unknown New York: The City That Women Built that she produced and narrated. In the film Willis told the overlooked story of women’s contributions to New York City architecture and planning. For the film, she mapped dozens of projects throughout Manhattan shaped by women “yet their works — their blood, sweat and tears — were either blatantly shunned, labeled as anonymous or credited to someone else” Willis said. The work was as much of a testament to the trials and tribulations women have faced in architecture as well as what she herself endured along her journey.

Willis was born in 1928 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. During the Great Depression, her father’s oil business went bankrupt and subsequently abandoned the family. Willis and her sibling spent years in-and-out of orphanages. After moving to Portland, Oregon for highschool; she enrolled at the University of Southern California in 1945, one of 200 women in the class. After, she studied aeronautical engineering at Oregon State University but transferred to University of Hawaii for a Bachelor degree in Art. She completed her degree in 1955.

After a stint working as an independent artist, Willis established her own firm in 1966. Her practice caught national attention after it converted three Victorian San Francisco homes into a restaurant complex. Willis would go on to win acclaim for her 1983 design for the San Francisco Ballet Building. The late U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein said of her relationship with Willis, “As mayor of San Francisco at the time, I was proud to work with architect Beverly Willis in creating this timeless monument to the arts.”

An activist, Willis firmly held the belief that architects have a responsibility to double not only as building designers but also leaders in society at-large. In 1976 she served as a delegate to the United Nation’s conference on Habitat. In 1979 Willis was elected as AIA California chapter president, the first woman to hold that title. One year later Willis helped cofound the National Building Museum in Washington D.C., a building programmed to “advance the quality of the built environment by educating people about its impact on their lives.” In 1995 she founded the Architecture Research Institute, a think tank that developed urban policies between academics, governments, corporations and the public.

It was in 2002 when the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF) was created. According to Willis, she started the Foundation “to fight to ensure that women in architecture have the same opportunities as men to realize their dreams and to be remembered. The creation of BWAF meshed with my broader lobbying efforts for change, including the 1978 resolution, passed by the American Institute of Architects, to support the Equal Rights Amendment,” Willis said. “Forty years later, the profession has yet to live up to the promise of equality. Whether women will finally be able to achieve democratic equality with men depends on our collective will to forge a new professional culture of inclusion. Working together, with financial support of all committed to this mission and with our innovative programs, research and leadership, we create a more equitable future for women in the building industry.”

In 2014 Willis received the AIA’s Gold Medal posthumously for Julia Morgan, the legendary California architect, and became the first woman to receive that award. It was also that year when she helped launch the internet project Pioneering Women in American Architecture which amplifies women’s contributions to American design, architecture, and planning.

Mary McLeod, a Columbia University professor, and Victoria Rosner from NYU both worked closely with Willis, and forged a deep friendship with the late architect. “Beverly Willis was a transformative and visionary leader in American architecture, both through her own practice and through her advocacy for women architects. In launching the foundation that bore her name, Bev imagined into existence a significant vehicle for supporting women in the building professions— still one of the most male-dominated in the United States. She opened up a space for the revision of mainstream architectural history to include women’s enormous contributions, contributions that had been largely erased by historians and architecture school curricula,” McLeod and Rosner told AN.

“Besides her groundbreaking films on women’s contributions to architecture, she envisioned the website that we have been co-editing for the last eight years. Pioneering Women of American Architecture is the largest effort to date to document the contributions of US women architects born before 1940. One of our very favorite profiles on the site is the one of Bev herself, written by her wife, architectural historian Wanda Bubriski. We will greatly miss Bev’s energy, dedication, and brilliance—she was, herself, a true pioneer,” McLeod and Rosner continued.

For years, Willis also volunteered in the AIA Women in Architecture program, offering mentorship for many. “I was introduced to Beverly Willis through a mutual colleague Claire Weisz back in 2013 and am forever grateful for each opportunity I had to connect with Beverly over the last 10 years,” said Venesa Alicea-Chuqui, an architect and Kean University professor. “I remember the first conversation I had with her over tea, she told me that diversity was my super power and she was excited to see the increase of women of all demographics coming into the profession,” Alicea-Chuqui told AN. “She will be missed. Her legacy lives on in all of us through the work of the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation and Women in Architecture committees across the country.”

“I met Bev (and Wanda) roughly ten years ago through a mutual friend from the Connecticut architectural community,” said Jessica Varner, an architecture professor and close friend who’s worked extensively about Willis. “Over the years, Bev and Wanda drew in a local community of feminist friends and creative thinkers who often gathered over dinner or would spend the day together at their home overlooking the Long Island Sound before the fall last full moon swim tradition in nearby Branford, and I was lucky to often get an invitation” Varner told AN. “Knowing how long Bev fought for gender equity in architecture inspired me and many others to push harder for a more just and equitable architectural profession. Bev’s sharp intellect, advocate heart, bold feminism, and ability to hold a feisty conversation with anyone will forever be missed.”