Exposed hardware, scaffolding, a coffin shaped like Mies’s Crown Hall at IIT, photography of Golan, chain link used by settlers to carve out the Jeffersonian Grid: These are some of the ephemera on display at the Chicago Architecture Biennial’s fifth iteration (CAB5) which opened last week. This is a Rehearsal is installed across Chicago, including at the Chicago Cultural Center, Graham Foundation, Blanc Gallery, Chicago Architecture Center, and James R. Thompson Center. It’s curated by Floating Museum, an art collective founded by avery r. young, Andrew Schachman, Faheem Majeed, and Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford.

This is a Rehearsal speculates “how contemporary environmental, political, and economic issues are shared across national boundaries but are addressed differently around the world through art, architecture, infrastructure, and civic participation, liberated from the temporal boundaries of finality” the curators say in their vision statement. Toward that end, CAB5 offers over 100 activations across Chicago convening 86 participants including Ruth De Jong, Jordan Peele, interim studio, Sam Levi Jones, Dream the Combine, SOM, Paa Joe, Kiel Moe, Chris T. Cornelius, David Benjamin, Norman Teague, Black Reconstruction Collective, Perry Kulper, and others around a loosely defined brief which yielded a kaleidoscopic multiplicity of responses.

Artist Faheem Majeed put his nearly two decades of experience at Chicago’s historic South Side Community Art Center to work at CAB5. “I don’t think curation is typically democratic at all,” Majeed told AN. “It was our responsibility to figure out how to make curation and our selection more horizontal. Many of the people we invited to participate actually weren’t interested in biennials. Many were fed up, or needed space away from the client-driven, commercial-based side of practice and wanted to do something experimental.”

The Chicago Cultural Center, known colloquially as “The People’s Palace,” dedicated several of its cavernous rooms for CAB5 stagings. 100 Links: Architecture and Land, in and out of the Americas by AD–WO and The Buell Center at Columbia University was formally beautiful, but the story it told was chilling. This piece created a cascading sculpture hung from the ceiling using tools of colonial settlement, namely Gunter’s chain, a rudimentary form of chain link. Following centuries of genocide perpetrated against Indigenous peoples, Gunter’s chain was used by surveyors to divide up the continent for extraction, land speculation, and development. 100 Links subverts the Gunter’s chain extractive logic by using it for art: The 66-foot-chains, divided with 100 links, are hung from brackets high up in the air and drape down to the ground like a Tiffany’s necklace.

The subversion and aestheticization of a tool concocted for brutality invites viewers to reconsider their relationship to land by defining the earth not as object, or property, but through relational measurement. “Typically when we think about the grid, we think of a map,” said Lucia Allais, director of the Buell Center. “But really this network was laid out by people with chains in their hands. [100 Links] connects the sublime to different kinds of aesthetics, beauty and horror, a theme which repeats throughout the biennial.”

Beauty and horror are paradoxically intertwined throughout CAB5’s plethora of activations. This tension motivates the installation by Jordan Peele, director of modern horror classics Get Out and Us, and Ruth De Jong, the set designer behind Peele’s recent thriller, NOPE. At Chicago Cultural Center, the ranch-style home from NOPE is reconstructed for the public, inviting visitors to consider the quotidian horrors and microaggressions that marginalized communities throughout the U.S. experience on a daily basis, acts which are central to the plots of Peele’s films. Peele and De Jong’s piece is in the room next to 100 Links, conceptually visualizing and threading the colonial violence which gave way to Manifest Destiny, and its architecture.

Ukwé·tase by Chris T. Cornelius, founder of studio:indigenous and dean of the University of New Mexico’s school of architecture, created a similar piece about alienation which acknowledges the complex relationship between Indigenous peoples and the land area that was renamed by white settlers as Chicago. Ukwé·tase is an Oneida phrase which translates to “newcomer/stranger.” According to Cornelius, Ukwé·tase is a self-described physical land acknowledgement. “As an Indigenous person, I’m a stranger in this land that is now called Chicago,” Cornelius said. “Ukwé·tase is about acknowledging this while tapping into Indigenous knowledge systems like Indigenous regalia, the jingles on women’s dresses that make noise, gears,” Cornelius remarked. “I often think about architecture as an animal. I think about how when I’m putting something into the world, I want it to be a good relative to our non-human relatives. Ukwé·tase is a piece you can immerse yourself in, and reflect on the place where you are.”

At the Graham Foundation, You Are The Voice; We Are Its Echo by interim studio’s Nora Akawi, Eduardo Rega Calvo, Khaled Malas, and Nadine Fattaleh showcases resistance to settler colonialism in Golan—which in Syrian translates to Jawlan—a region 20 miles north of the West Bank that was annexed by Israel from Syria in June 1967. Part library, part audio-visual installation, You Are The Voice; We Are Its Echo engages the Israeli military’s destruction of 250 Jawlani villages and farms in Golan post-1967 and the Israeli settlements that were built on their ruins.

The piece by interim studio takes its name from a phrase that Jawlani people chanted on Golan’s border with Syria in 2018 during a demonstration—“Antum Al-Saut; We Nahnu Sadah”—which, according to the curators, made “audible the demands, dreams, and aspirations for freedom that defy enclosure.” Through maps, testimonies, and historical documents, it tells the story of resistance to occupation; a draped mannequin watches over the room.

On the floor below, a photography exhibition–slash–art installation by Dream the Combine centers more episodes of state violence inflicted on communities of color by police in Minneapolis in the summer of 2020 after George Floyd was murdered. Other rooms at Graham Foundation contain remarkable works by Larissa Fassler, a Canadian artist practicing in Berlin, and Chicago-based visual artist Cecil McDonald Jr.

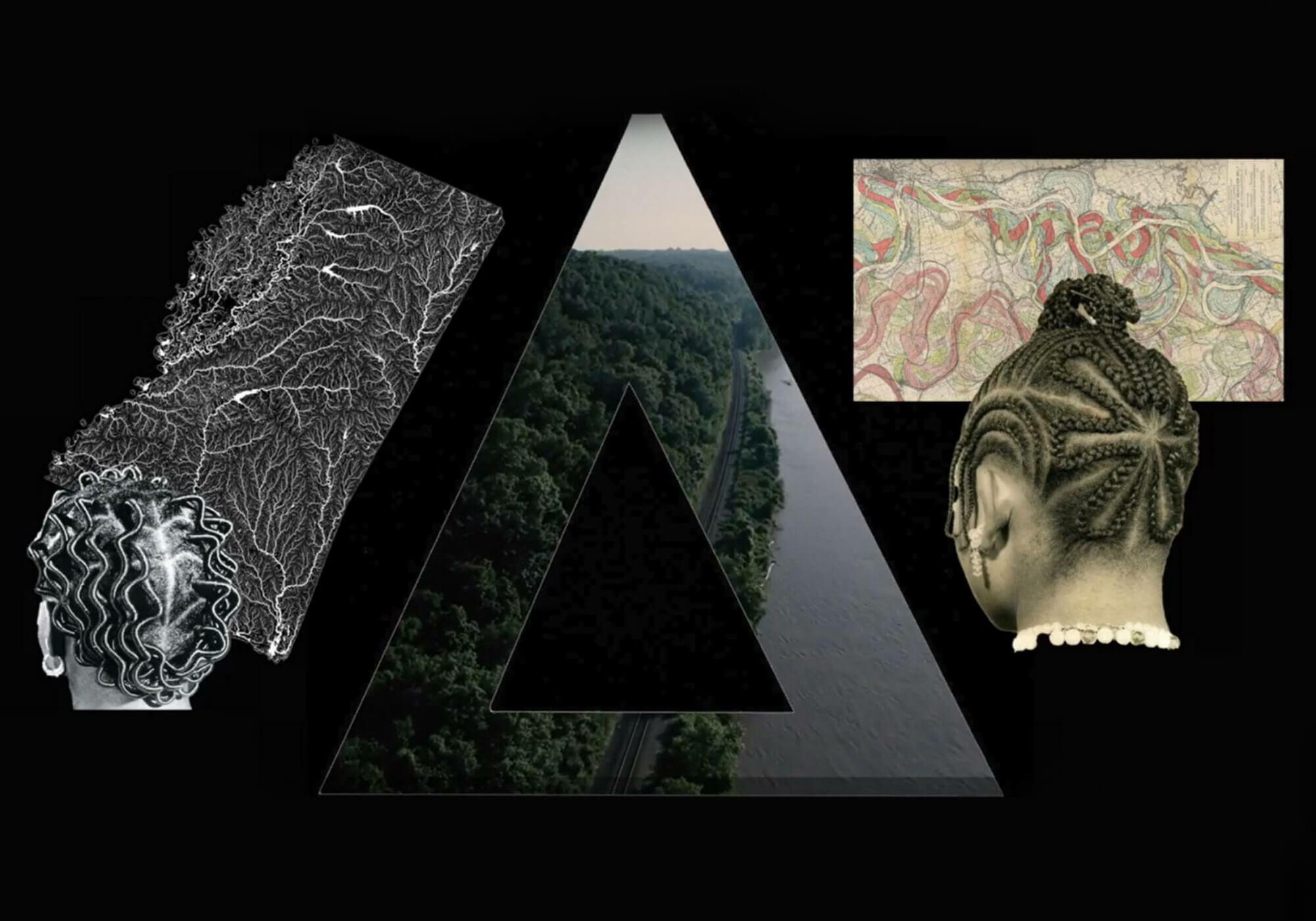

Black Reconstruction Collective’s contribution to CAB5, sited at Blanc Gallery in South Side Chicago, is called UNMONUMENT CHICAGO: After Work; its ten installations will travel to cities throughout the U.S. when the biennial closes on February 11, 2024. At Blanc Gallery, Zion Estrada from Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC) debuted her short film, 2,340 Miles from 1880. Previously reviewed by AN, the work draws from the archives of Homer McEwen, the great-uncle of BRC cofounder Mitch McEwen. Estrada’s film tells the story of work stoppages by African Americans on Louisiana plantations after the U.S. Civil War, and how this history of resistance continued in Chicago throughout the Great Migration. Brooklyn artist Olalekan Jeyifous designed a custom industrial lift to host Estrada’s film, occupying a prominent, central space in Blanc Gallery’s courtyard.

Also at Blanc Gallery, photography by artist Patrick McCoy adorns the walls showcasing South Side Chicago in the 1980s. At First Glance is a photo exhibition by McCoy which depicts African American men, many living in destitute poverty, whom he saw while riding his bicycle to work between the South Side and the Loop. At CAB5, McCoy told visitors that he never thought of what he was doing as art, nor photography, but rather journalism that explored state enacted violence on African Americans perpetrated by the Reagan administration during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. At CAB5, McCoy’s photographs appear in close proximity to Estrada’s short film, and Amanda Williams’s installment Redefining Redlining which traces racial segregation in Chicago.

Throughout CAB5, there were also times when the horrors and gravity of the global moment seemed to outweigh the content on display. And at certain points, reality kicked in.

At the James R. Thompson Center, Helmut Jahn’s 1985 postmodern classic for the State of Illinois in Chicago’s Loop—now slated for a major renovation by Prime/Capri Investment Group for Google—hosted separate installations by Storefront for Art and Architecture, Marya Kanakis, Ibrahim Mahama, Inference, Joel Putnam, Stoss Landscape Urbanism, Seel Studio, National Public Radio, and the University of Stuttgart.

The installations were impressive in their own right, but in person, murmurs from critical Chicagoans over the future of the beloved public complex at times overshadowed the items on display sponsored by Thompson Center’s new owner. If putting trees on skyscrapers under the guise of sustainability is greenwashing, then what is hosting architecture installations in a memorable public space just before it’s privatized to foster an image of corporate benevolence? Cue the butterfly meme: Is this biennale washing?

Still, This is a Rehearsal successfully achieved what it sought to do: It provides a platform for participants to experiment and to show what a more democratic, horizontal biennial that touches every community in Chicago may look like; it gives visitors a glimpse into a forthcoming monument dedicated to Anna and Frederick Douglass by Norman Teague Design Studios; and it connects innovative programs happening in the city, like the Chicago Tool Library and Urban Growers Collective, with opportunities to engage with the public and grow as enterprises.

If in 2015 the Chicago Architecture Biennial set out to determine the state of architecture, its fifth version is a clear manifestation of the fact that architecture’s priorities, scope, and practitioners have changed dramatically for the better.