Architect: OSO

Location: Vancouver

Completion Date: 2023

An office tower composed of a shifting cluster of glass boxes, straddles Vancouver’s Business district and cultural center. Designed by the Japanese firm OSO for Deloitte, one of the big four accounting firms, the building attempts to balance the character of the city’s business sector with the experimentation of its civic architecture. During the design phase, particular attention was paid to two nearby works by architect Moshe Safdie: The Vancouver Central Library and the Centre for Performing Arts.

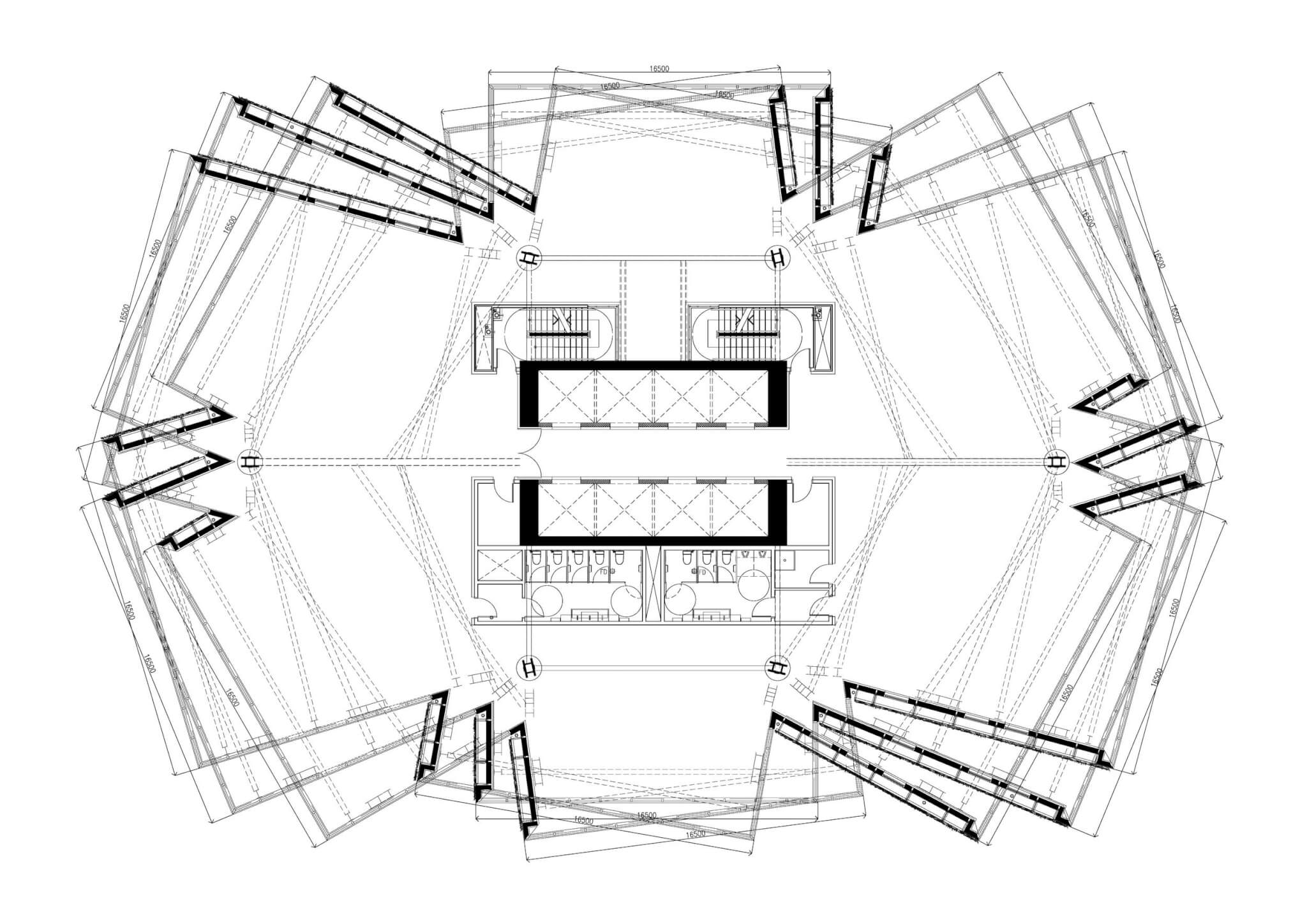

The complex massing of the new tower creates a unique profile no matter the orientation it is viewed from. Yet the building’s seemingly random appearance is based on a rational organization of cantilevered volumes. Its most basic unit is a 4-story high glass cube. 6 such cubes were combined to create a single unit. The design team created 3 standardized cube arrangements, 2 of which are repeated on the tower. Each floor arrangement offsets its volumes from that of the floor below it, contributing to the structure’s distinctive sculptural quality.

An elevator core rises through the center of the structure supported by six large columns which scale each floor of the building. Besides these, no other columns interrupt the floor plate. The cantilevered glass boxes are instead hitched to the core through a system of trusses along the facade which transfer the perimeter load between volumes.

The sporadic geometry of the envelope creates an irregular floorplate, allowing for compartmentalized office layouts, greater daylight penetration, and a multitude of sightlines to the surrounding city.

Glass was chosen, in part, to enable these views. Esteban Ochogavia, founding partner of OSO, told AN that “views of the surrounding landscape like the mountains and the bay are so important that most high-rises in downtown Vancouver use glass curtain walls.” Moreover, glass was selected to “make the building lighter, more abstract, and create a variety of reflections that would make it less monolithic.”

To combat solar heat gain, portions of the tower were made opaque through an aluminum panel system. Each of the tower’s distinct volumes—of which there are many—features an opaque face. These walls store much of the building’s mechanical systems, louvers, drains, and ventilation. Perforations were applied to the panels to accommodate ventilation requirements.

Further strategies to overcome solar radiation include the use of a triple-glazed curtain wall system. According to Mitch Sakumoto, principal at Merrick Architecture, the project’s executive architect, “an energy model and minimal sun study was undertaken and the main issue with the all-glass facade was glare within the office floor plate.” Sakumoto explained that placing the cubes at different orientations reduced solar gain much more than if the floor plan was rectilinear.

The building is targeting LEED Platinum certification which is currently under review by the Canadian Green Building Council (CaGBC).

Mirrored soffits were placed beneath the cantilevered cubes, increasing light penetration within the building and adding to the structure’s visual complexity as the volumes beneath appear to be reflected infinitely upwards.

Sakumoto added that technical challenges arose in relation to the building’s steel structure. “The mechanical and electrical systems had to be coordinated through the large steel beams using castellations or openings so the mechanical and electrical components could reach all areas of the floor plate as required. The number, size, and distance between castellations within a steel beam were dictated by structural requirements so a lot of coordination was required to achieve the required clear floor to ceiling dimension.”

The project’s timeline moved extremely quickly and the architects were still designing portions of the building when construction began.

With Deloitte Summit, OSO experiments with one of Vancouver’s dominant architectural forms—the glass tower—demonstrating that office buildings don’t always have to be boring.

Project Specifications

-

- Architect: OSO

- Location: Vancouver

- Completion Date: 2023

- Client: Westbank

- Architect of Record: Merrick Architecture

- Landscape Architect: HAPA Collaborative

- Structural Engineer: Glotman Simpson

- Mechanical Consultant: Norman Disney & Young

- Electrical Engineer: Nemetz

- Code Consultant: LMDG

- Lighting Consultant: Ombrages

- Construction Manager: Ellis Don