Kwong Von Glinow isn’t afraid to uplift the mundane. Based in Chicago, the studio finds inspiration and freedom in historic templates of development.

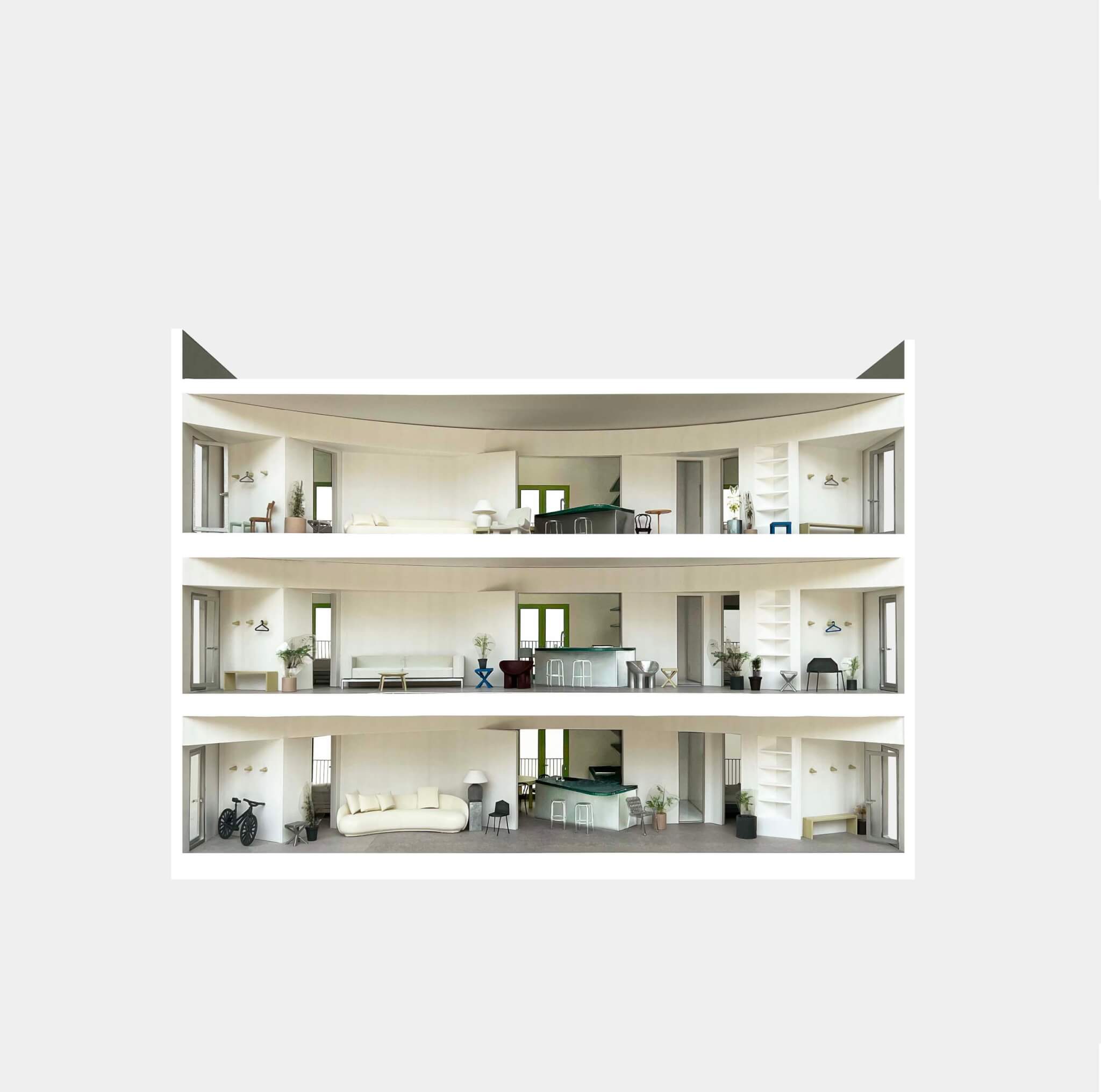

For There is Room, a recent exhibition at MAS Context, the studio presented a compelling group of half-inch models and supporting model photography. The models’ large size allows viewers to get a close look at the spaces and how they might be inhabited. The studio works with familar typologies to realize their considered projects: For example, they investigate the Chicago 3- and 6-flats, which have efficiently housed working-class people for more than a century.

AN’s Executive Editor Jack Murphy spoke with studio cofounders Lap Chi Kwong and Alison Von Glinow to learn more about their ambitions for the exhibition, their current work, and how they use models to communicate with their clients and create images of architecture.

Jack Murphy: Why big models?

Kwong Von Glinow (KVG): We use models to start the design conversation for every project. We stand around the model and test out different ideas very casually, without precision because the point is to see what starts to work and also what doesn’t work. “What if we take out this existing wall? What if we angle this room? Should we make an opening on this side? If we move the stairs here, we can bring in more light over here.” The goal is always to push the spatial experience of the project and the model is all about space. Modeling is how we practice architecture.

We also engage our clients through the models. Models are a means of communication that offer a fuller understanding of a proposal. While renderings offer selective and curated views, a model on the other hand shows the full space. Vantages that weren’t captured in a rendering can be understood. Perhaps most importantly, models can be touched. They are a working tool where all hands (architects, consultants, clients, contractors) can be present to manipulate and discuss the design.

JM: Can you tell us a bit about how you use these models? Are these for research or presentation or to be used during the design process?

KVG: In the exhibition There is Room, we showed 5 models of 5 different projects. Each of these models was made specifically for the exhibition. Previously, similar models had been made for each of the projects at least once during the design process. For instance, the model of Ardmore House in the exhibition was probably our sixth iteration.

Starting from concept design, we quickly build many foam core models because the material is easy to cut and pin together—assembly and disassembly is fast, and the goal with these models is to quickly generate ideas. The model is not the outcome of the design, but rather the model is part of the design process. They are not pristine. They have pin marks, residue of ripped off double-sided tape, layers of wallpaper finishes, etc. When we have presentations, they reflect the process. We like to share how we got to where we are by showing the development.

JM: What information do you use to create the models? Do you work from 3D scans or photos with as-built drawings?

KVG: For renovation and addition projects, we start with photos of the existing space and as-built drawings, and very quickly we move to 3D scans to ensure the precision needed for the project. The photographs of the space are photoshopped and mapped as surface treatments. For instance, for a landmarked home in Highland Park that we are both renovating and expanding, we wallpapered our foam-core models with the marble floors, historic woodwork, and ornate fireplaces in the spaces that required preservation.

JM: Your teaching at the GSD and Princeton involved students making big models. How are these useful pedagogically?

KVG: We start off each studio with an exercise called “Smuggling Architecture.” The exercise inserts architectural ideas into developer housing unit plans (the Chicago three-flat for Princeton and the Chicago six-flat at the GSD). We give a 45-minute tutorial where we build together as a studio: someone cuts all of the walls at 4-½” tall; someone creates the window openings; and others pin the interior walls together for closets, bathrooms, and kitchens. Once the developer unit is completed, we quickly modify the design together. The use of the model allows students to investigate the building effect versus an architecture effect. It becomes clear quickly the effect that reconsidering the design spatially can have on the building, the unit, and occupant.

JM: The models are populated with the stuff of life: furniture, plants, etc. How do you consider/think about these items when designing?

KVG: This aspect of model-making has evolved quite a bit in our practice. When we started our practice, we made furniture/objects to define different uses of a space or a room. In those models, the furniture and objects were more abstract. It was not meant to be a 1:1 representation but to give an abstract sense of life. Three of the projects in There is Room are multifamily housing projects, so each unit reflects a different way of inhabiting the same building to show possible variations.

JM: You’ve also staged and photographed the models yourselves, outside of this installation. How do you produce and use these images in your office? Do you share them with your clients? How do they relate to computer renderings?

KVG: We really enjoy documenting the spaces of the models. Out of the five models exhibited, only Ardmore House has been built so far. For Ardmore House, it is validating to see the images of the model give the same light qualities as the built space—some even look almost the same as photographs of the built space. Natural light has a lot to do with the unique qualities that model photography gives. It is very hard to simulate natural light in renderings as truly authentic.

Our technique to achieve this realism in the model is very low-tech. We just use an iPhone, which we can easily move around. But we typically do not take a lot of model photos before a client meeting. We like to discuss the project with the client using the physical model, and the photos usually become the meeting notes.

JM: One of the models is of a 6-flat scheme proposed for Come Home: Missing Middle Infill Housing, a recent CAC competition. Your 3-story building has a distinctive, deep facade that creates two courtyards, one on either end of the massing. Can you tell us a bit about that design?

KVG: When we started our office, we did a lot of self-initiated research and projects. We have researched Chicago single family houses, the Chicago 3-flat and 6-flat for nearly four years now. We see there is a lot of potential in these typologies, especially given that these types are relatively simple to work within the Chicago standard lot size.

When we started designing for the Come Home Chicago Six-Flat, we began with the site: a 50-foot wide lot is essentially a double lot, which is rare and holds a lot of potential for developers as they can decrease the cost per unit in this relatively small scale of multifamily housing. Standard lot sizes are 25 × 125 feet, while the double lot is twice that at 50 × 125 feet. Typical 6-flats take their cues from the 3-flat archetype, which is a long and narrow unit down the length of the lot. The 6-flat simply mirrors that.

But we wanted to work with the lot width and exaggerate the frontage as much as possible, so we put the units front-to-back instead of side-by-side. The deep courtyard allows the living space of the apartment to have full-height glazing and at the same time have some privacy from the street or alleyway. By bringing in a deep courtyard, we more than double the front facade of the unit, which brings in more light and air to the apartment unit.

JM: Can you tell us more about this Art Outpost project?

KVG: The Art Outpost is a renovation and rooftop addition to an historic Chicago greystone about two blocks from the United Center. We think this is one of our projects that really benefited from model-making. The project is very simple: Our client wanted the biggest roof deck possible to host events for contemporary Chicago artists. So, we cut out a piece of foam core that respects the property’s setbacks, then we rotated this “deck” slightly. Then, the space under the deck functions as a new gallery space for the clients. Formally and materially, this project responds to the idea of a deck. We are very excited that the project was recently permitted and will start construction soon.

JM: One of the models is of Ardmore House, which is your own home. How did the translation work between model and building for you? Was it as expected now that you’re living in it?

KVG: The spatial qualities between the model and the actual house are very similar. We think one difference is that the model as an isolated object shows an interior-focused project. In the office and in an exhibition space, this is shown by how we peek into the model to engage with the spaces inside.

On the contrary, Ardmore House as a built space has a very similar interior quality to what we designed in the ½”=1’-0” scale model, but at the same time, now that we are in the building, we see the space is also very exterior-focused. The house becomes quite urban, as we see the neighbors, live and work along the alley and street, and witness all of the seasons.

JM: Two of the projects contain a shallow, arcing wall that runs the full depth of a floor plate. It is kind of like an enfilade-hallway-room… What do you like about that shape/use of space?

KVG: Yes, we really like this idea—something like a big circulation space yet defined enough to be a space to gather and use. One of the reasons for creating this type of open-ended space is that we hope to minimize circulation-only spaces in our projects where spatial efficiency is important.

The arching walls in these schemes are true partial circles. It is a curve that is not formed by random points, but every segment of a circle is the same. This is very important for buildability. The curve may look custom, but everything about it is actually standard.

We also used a variation of this designed arc for a library renovation project at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where we discretize the arc with sawtooth nooks for study spaces. The leftover space is what we call the “corridor +” which serves as a plaza for the library. It has been fascinating to see how this spatial technique is useful in both a library context and a single-family home.

JM: The exhibition text mentions the realities of “comps,” but it also raises the question of type as a thing that architects study and discuss. Is type something you think about often?

KVG: We aren’t obsessed with type, but we do like types because they always work. We think the reason there is a certain type of 3-flat or 6-flat is because people like it, people are used to it, and it is functional. What we would like to do is consider the future of the type: How can we improve it? Often, types are considered final and static, but we hold optimism that there is room to reimagine their future.

JM: What feedback/exchange did you receive during the course of this show at MAS Context? Did anything surprise you?

KVG: We designed the exhibition to put models at the center of the show. They were the objects we created, and any 2D visuals came from the models. It was very deliberate not to bring in any other types of representation. There was a lot of excitement from visitors to see models and model photographs—and even perhaps shock that we actually build models at ½”=1’-0” in our office as a design process. We got a lot of comments that people hadn’t built models in years. I don’t think we expected that much enthusiasm for models, but we hope it stirred up some passion for more models to come!