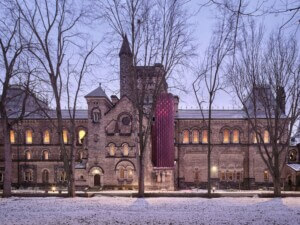

The storied history of Detroit’s Book Tower and Book Building begins with their architect, Louis Kamper. Dubbed a “cake decorator” by local press, he collaborated with the zealous Book brothers on their quest to build Detroit’s tallest building. Completed in 1926, Kamper’s work defines Detroit’s arterial Washington Boulevard and set a precedent for much of the city’s urban fabric—Italianate Renaissance meets industrial past. The Book Tower flourished as an office tower during the pinnacle of Detroit’s industrial age, but the building fell into disrepair as the city’s industry dwindled away and tenants moved out.

Today, however, it seems like just about every city is contemplating how to convert office space to residential and mixed-uses uses, and this storied building is finally entering a new chapter. The Book Tower is made up of the ROOST Detroit extended stay hotel, The Residences at Book Tower, Anthology Events, office and retail space, seven food and beverage concepts, and other amenities. An extensive, seven-year long renovation of the Book Tower and the adjacent 13-story Book Building was led by New York–based ODA Architecture and local developer Bedrock with the goal of renovating Kamper’s original designs while also adding modern amenities. The architects and developer also worked closely with local historic consultant Kraemer Design Group and the State Historic Preservation Office. The building is located within the Washington Boulevard Local Historic District.

ODA’s labor of love required careful engineering to renew a landmark marrying past and present. The firm’s careful interventions are apparent on a variety of scales from intimate details—such as the restoration of a brass cherub clock still ticking above the lobby—to the urban scale, as the Book Tower responds to the surrounding neighborhood where other adaptive reuse and restoration projects are taking hold: Kamper’s Book Cadillac Hotel just reopened after a restoration and down the street, the Kalamazoo Beer Exchange operates from within a former YMCA facility, completed in 1901. Throughout are details where new was made to look old, where old was left alone, and where you look around and find yourself asking: this wasn’t always here?

Both structures are named for brothers Herbert, Frank, and J. Burgess Jr., Book who went into business together in the early 20th century during the heyday of Detroit’s industrial wealth. The Books had a good working relationship with Kamper—a German architect fluent in the new-made-to-look-old ethos, evidenced in his extravagant use of ornamentation ideal for flaunting wealth—when they tasked him with designing the city’s tallest building. It was designed in line with other Kamper buildings and followed suit with earlier structures in the neighborhood—notably Romanesque and early Victorian masonry ensembles. Following the tower’s completion in 1926 the brothers already had plans for another tower, rising a staggering 81 stories, to be erected adjacent to the 38-story Book Tower. Only two floors of the twin, were ever realized, and are currently under restoration, as the onset of the Great Depression stunted the grand plan.

By the 1960s population decline and stalling economic growth caused office tenants to move out, with the last, Bookies Tavern, moving out in 2009, ushering the building into a final state of disrepair.

Bedrock purchased the property in 2015 with its eyes set on restoring nearly every nook and cranny of the property, from its copper crest to its 2,483 windows. For the design team, deciding what to keep and what to embellish or reinterpret was “a strict process,” Gene Pyo, project director at ODA, told AN.

“For each element, discussions were held to determine if and what changes could be made and for what reason,” Pyo added. “This comprehensive process applied to everything, ranging from adding an entirely new brick building on the roof to changing the paint color of a pattern on the elevator door.”

To step foot in the atrium of the Book Tower is to step back in time. The marble walls and floors glimmer under the light of restored chandeliers and light beaming through the glass skylight. Fresh coats of paint on the ceiling plasterwork are just as alive as they were in the 20th century. It’s easy to be overstimulated by the detailing and grandeur of the space. The attention to detail becomes immediately apparent as does the care taken to craft the past with the present.

When still a functioning office building, the domed skylight and barrel vault crowning the three-story atrium were filled in to accommodate more workspace. At the start of the renovation, when the skylight was unveiled again it was coated with tar and nicotine in addition to broken and missing glass pieces. A few grainy, black-and-white images as well as a section drawing of the decorative glazing provided the designers with guidance for replicating and reinterpreting the historical element.

“The building held such significance in the city’s history that we felt an obligation to strive for historical accuracy in our restoration efforts—anything less would have done the building injustice,” Pyo said. “We dedicated considerable time to analyzing old drawings, photographs, and conducting thorough research. Over the years, some historic elements had been lost, and haphazard additions were made. We identified and removed these elements to restore the original design.”

The restoration process began with taking count of what was there and carefully removing the individual panels to be restored at a shop in Philadelphia. Existing glass panels in decent shape were cleaned with water and a non-ionic surfactant and placed back in place. A 3D laser scan of the entire structure allowed for the broken and missing glass components to be digitally modeled. The restoration was akin putting together a 6,000-piece puzzle: an archival image determined the location of certain elements based on pattern and shape. The metal frame of the barrel vaulting, alongside the skylight and forming the structure of its lower arches, had to be completely recreated.

New was made to look old here, as visible in the patina applied to the bent bronze bars, giving them that always-been-here appearance, and in the new balustrades around the atrium, custom-crafted from stone.

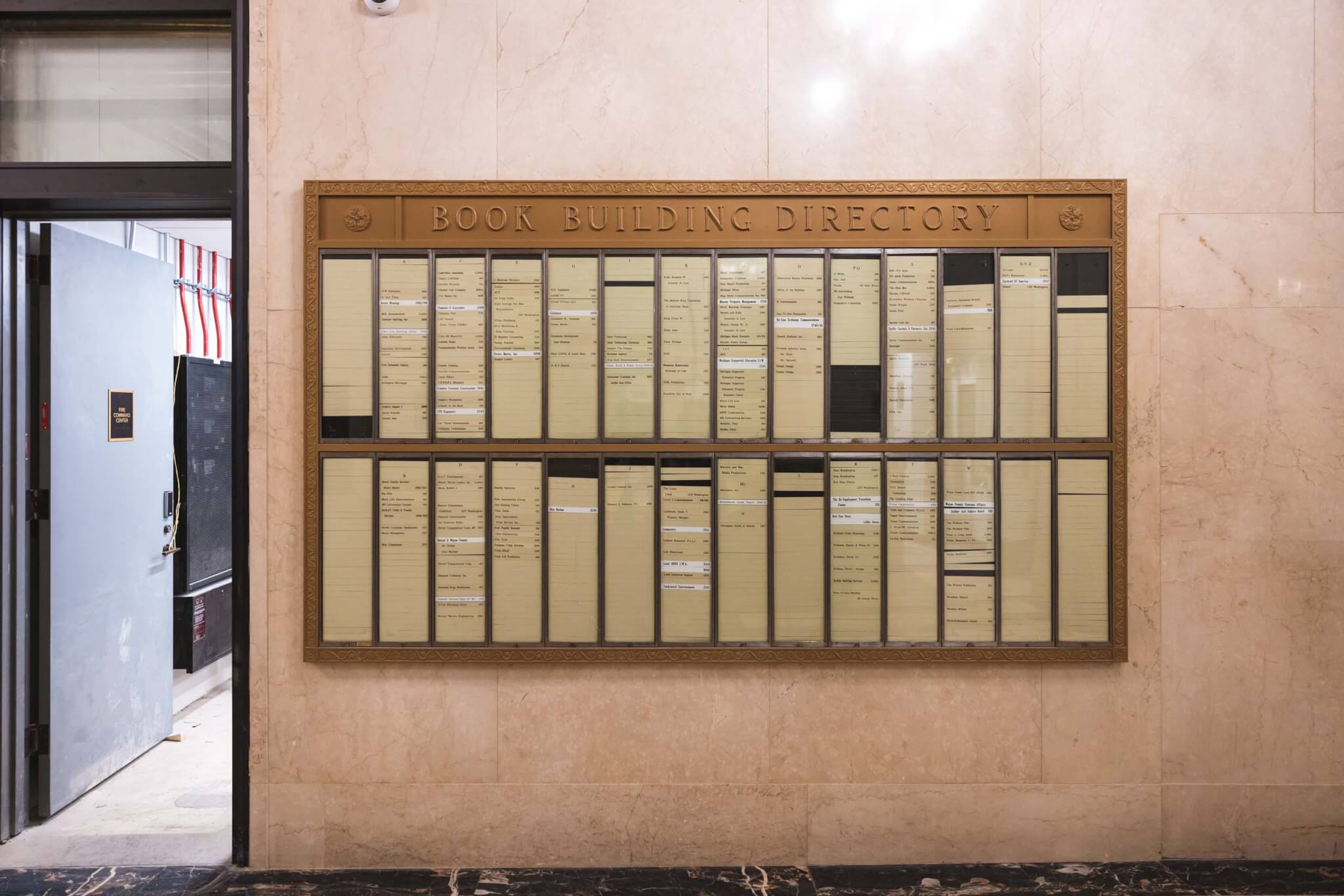

“Personally, I loved preserving the details from the original because that’s what really adds to the character throughout: the original gold clock, bronze mail chutes, directory in the lobby with old tenant names, all bring charm to the building,” Pyo added. Elsewhere in the lobby, a bronze-framed directory hung on the hall listing past occupants was intentionally left during the renovation; the architects kept the piece in situ as a reminder of what once was.

At every corner a thought-out and considered detail presents itself, from the small scale such as a bronze post box slot (no longer functional) to contemporary art pieces (hotel guests receive a brochure detailing the works on display), a trash room hiding behind an elevator door and interior windows that once served as the building’s HVAC. Blink and you might miss something, walk through it a dozen times and there’s always a detail waiting to be discovered or a story you haven’t heard yet. The stories reveal themselves through the objects and decorative elements. Among these narratives are the old lists, ledgers, and receipts left behind from past tenants and found during construction—several of which have been preserved and are on display in the lobby exhibition.

The space is given a new, refreshed life with seven brand-new food and beverage elements. A new metal structure forms a casual bar venue toward the back of the atrium, and a French restaurant presents as if teleported in from Paris, and there will be two “posts” serving up savory Japanese cuisine. This spring, a service alley is also set to be converted into a public art space activated by a 180-foot-long mural.

There are 229 residential units—a mix of studios, one-, and two-bedroom units—and 117 apartment hotel suites with fully equipped kitchens, a gracious living space, and ample-sized sleeping area. Studio apartments start at $1,500 a month. Working from the former office layout and with two disparate structural systems posed a challenge when divvying up apartments and guest rooms, but the result is that each unit plan is unique. Elevator lobbies and corridors are living time machines, with veined marble work circa 1920. Floral motifs on the elevator doors were repainted to match what was. Light fixtures throughout the project were either restored or carefully curated. Replastered and repainted ceiling, archways, and gold accents offer a contemporary take on an old motif.

A highlight of the new space is a room previously used by the office tower as an auditorium: It represented an opportunity waiting to be tapped into, literally. Elegant metal framing was subdued by a concrete roof until ODA replaced it with glass. Sunlight and moonlight beam into the newly flexible event space. Nearby, Kamper’s affords a discerning few with views out toward Washington Boulevard and Kamper’s extensive portfolio of Detroit design work.

“In a way, the history of the Book Tower has embodied the ups and downs of the city over the years, and it’s exciting that the reopening of the Book Tower is pointing toward a bright future,” Pyo said.

The Book Tower’s reign as the tallest building in Detroit was short lived, dwarfed by the Penobscot Building in 1928 and the Detroit Marriott Renaissance Center today, but its character has endured. The building has entered its next chapter, but not without looking back at its past. A small exhibition on the building’s history occupies a room off the lobby, and an ongoing project spearheaded by the Detroit Historical Society is collecting oral histories from those who worked there to keep the narrative alive.