While the Barcelona chair is perhaps the most iconic example of furniture denoting a specific site—originally designed by Mies van der Rohe for the King and Queen of Spain, no less—it has long since transcended its namesake pavilion. More obscure, and possibly more covetable, are furnishings from another romanticized city. Object Chandigarh, a new book and exhibition, showcases a selection of furniture from a rare success story among master-planned modernist metropolises. Collected over several years by furniture dealer George Gilpin, most of the pieces cataloged in the book were on view at Patrick Parrish’s eponymous gallery in Tribeca, a showing which turned out to be the space’s last offering: Parrish recently announced that he was closing his street-level gallery in Tribeca and relocating to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The coffee table book’s short introduction tells the backstory of how the city came to be, more or less ex nihilo, following partition of India in 1947. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru envisioned a “new town, symbolic of the freedom of India, unfettered by the traditions of the past—an expression of the nation’s faith in the future.” The rest is history: Le Corbusier is credited with the ambitious plan (picking up where American architect and planner Albert Mayer left off), as well as a number of administrative buildings and sculptures throughout the city.

The architect entrusted much of the scheme’s actual implementation to his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, who spent a decade in the city overseeing its execution, from the design of several buildings down to the furniture throughout. His residence has since been converted into a house museum.

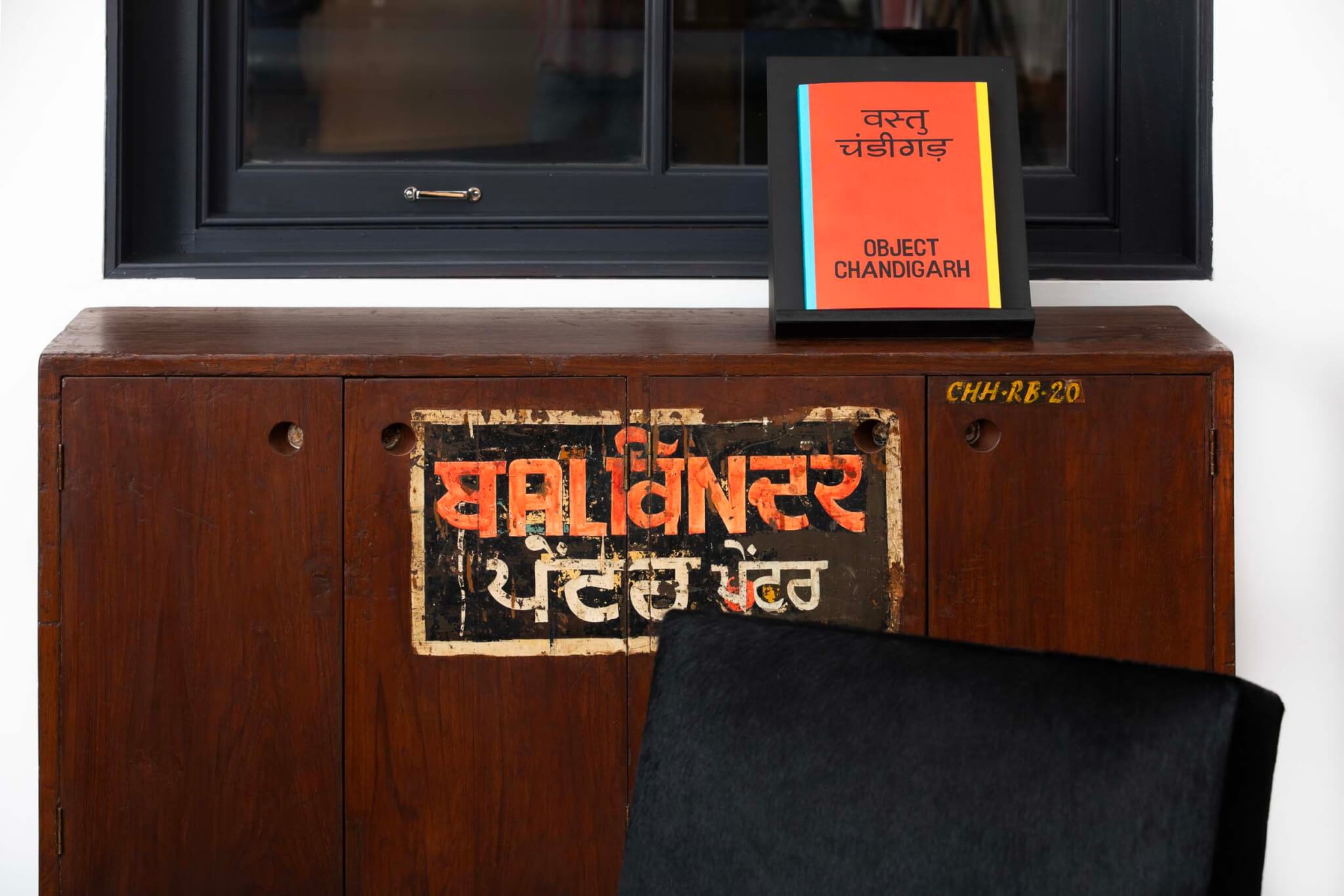

Object Chandigarh features a selection of around 50 original furniture designs (mostly seating) including a signature series of occasional chairs with sawhorse-like legs that resemble Jeanneret’s designs for Knoll. Others feature hairpin legs, now shorthand for MCM. Truth to materials reigns supreme: Each of the chairs and stools was crafted in local workshops in a material palette of teak and steel, plus a few upholstered and caned pieces, case goods, an executive desk, and floor lamps by Charles-Édouard himself.

But are they worthy of the “The City Beautiful” designation? (Chandigarh’s nickname is derived from the belle epoch City Beautiful movement.) The undeniable charm of well-loved objects notwithstanding, it’s a matter of taste: As fossilized modernism of a distinguished vintage, they’re importable relics of a faded dream of a better way of living, here tinted with the exoticism of Indian provenance. Mostly dating back to the mid-to-late 50’s, the pieces are nearing or past retirement age, which also makes them roughly the same age that Corb was when he designed Chandigarh. However tenuous the connection between the scale of Nehru’s vision and the works on view, it’s precisely their signs of use that makes them so compellingly auratic.

Yet their hard-earned patina, which is floridly extolled by writer Simon Andrews in a brief essay that introduces the book, somehow belies their provenance. Battered but intact and mostly restored to good working order, the pieces could well be lucky flea-market finds—Gilpin, a New York–based furniture dealer, implies as much in a Medium post, which does not appear in the publication—but their origin isn’t obvious at a glance. Their relative obscurity may well contribute to their cachet as IYKYK touchstones for collectors, and the book intentionally strips them of context, presenting individual tables and chairs uniformly photographed against a flat white backdrop as objets d’art along with detail shots that are almost lurid; only a series of Chandigarh cityscapes at the end of the book allude to their storied history.

The exhibition, for its part, gathers pieces in anthropomorphic clusters and showroom vignettes; a simple but effective scenography of Ellsworth Kelly–esque, primary-color panels in gallery’s entry foyer matches the design of the book and accompanying poster., which may be the only objects within reach for many of us. The stools start at $4,500; the chairs are perhaps a better deal at roughly the same price or a bit more, considering that a new Barcelona Chair costs over $8,000. Plus, secondhand goods are generally more sustainable than new ones.

The staging in both the gallery and the book affirms that these objects are now regarded as collector’s items or museum pieces. For a fuller picture, one would do well to track down filmmaker Amie Siegel’s 2013 piece, Provenance. The art documentary interrogates the booming secondary market for Chandigarh cast-offs in a series of long tracking shots sequenced in reverse-chronological order, starting in the posh abodes of collectors before proceeding to auction houses, restoration workshops, a container ship, and finally to a piece’s natural habitat in an odd corner of Corbusier’s fantasia. A cinematic meditation on value, heritage, and the legacies of modernism and colonialism, the film provides visual context that Object Chandigarh is lacking. In a knowing twist, Siegel elected to produce the 40-minute documentary in an edition of five, each of which were acquired by the likes of the Met and the Whitney, making it scarcer than its subject matter. Adding further layers of meta-commentary, Siegel produced a companion piece, Lot 248, a video of the auction of one edition of Provenance, as well as an art book compiling reproduced auction-catalog pages featuring Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture; the volume will set you back about $400 on resale marketplaces lately.

If Siegel’s institutional critique is a bit too on-the-nose, Gilpin, for his part, narrows his focus to the pieces themselves, offering a chance to own a bona fide piece by a legend (Corbusier or Jeanneret, take your pick). Tangible though they may be, it’s rather less clear if these pieces truly encapsulate the original spirit of Nehru’s utopian ambitions or if Chandigarh is now merely a 1stDibs search term for design aficionados.

Given the news about Parrish’s relocation, Object Chandigarh serves as a quiet swan song. Thankfully a dedicated Instagram account complements the book and exhibition, featuring archival imagery as well as behind-the-scenes photos depicting the furniture in various states of use and disrepair. (Parrish’s own newly redesigned website also catalogues past shows on Lispenard Street.) The digital format may not be what Nehru meant by “unfettered by the traditions of the past,” but it might just be the most appropriate medium for preserving the project for posterity’s sake.

Ray Hu is a Brooklyn-based design writer and researcher.