A Western District of Virginia judge recently granted Swiss architect Valerio Olgiati’s motion to dismiss defamation claims brought against him by Markus Breitschmid, a professor at Virginia Tech’s School of Architecture, after Olgiati sued Breitschmid for breach of implied contract and unjust enrichment. The case related to compensation has been filed in federal court and remains ongoing.

Olgiati and Breitschmid “had a long-standing professional relationship…that began in 2006,” Breitschmid told AN. Among other efforts, the collaboration resulted in Non-Referential Architecture, a book published in 2018 that Olgiati ideated and Breitschmid wrote. The dispute, Olgiati v. Breitschmid (7:23-CV-00352), concerns a private residence commissioned by Breitschmid for a site in Riner, Virginia.

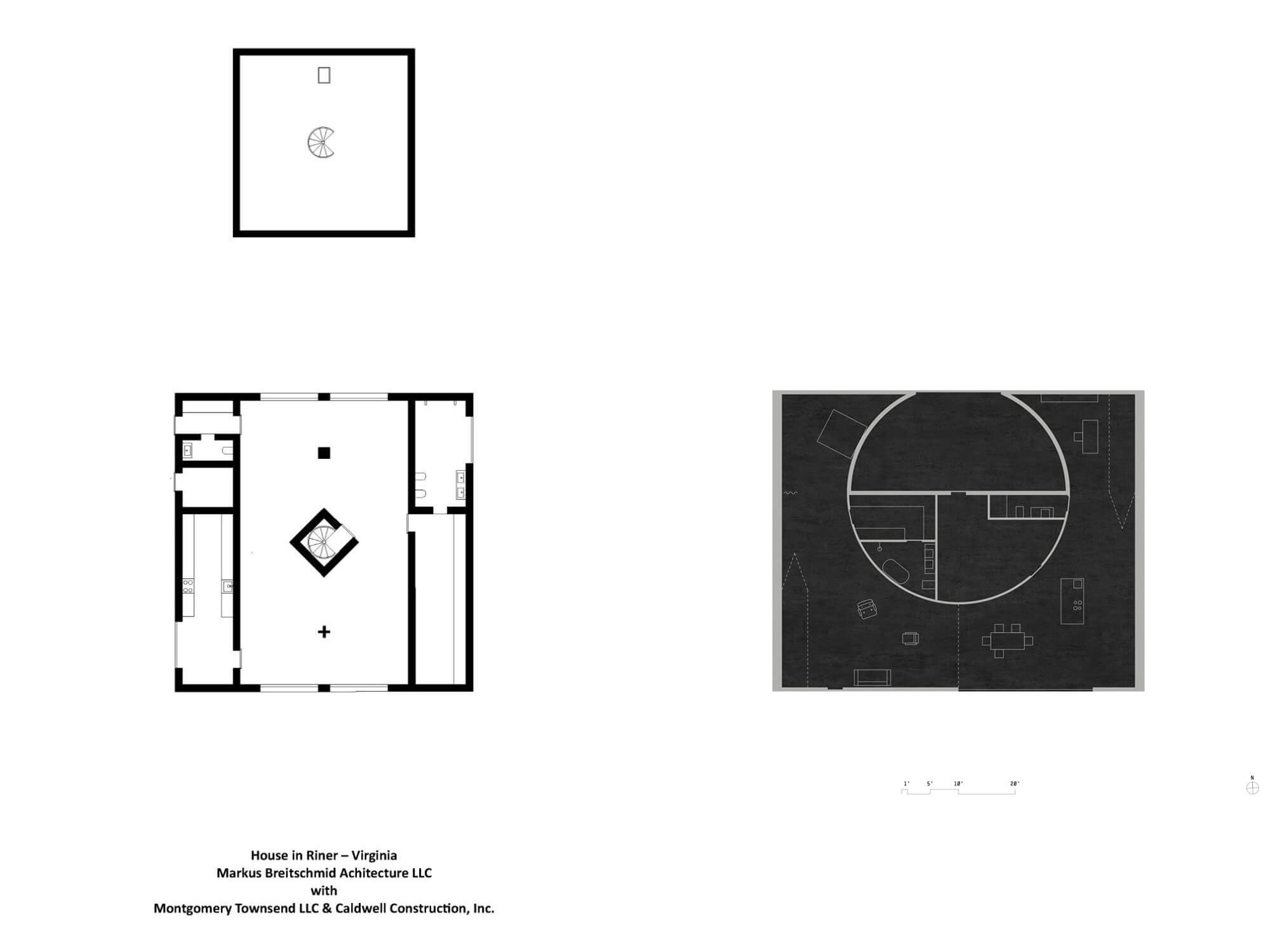

According to court documents, Breitschmid and Olgiati first discussed building a house together in 2013 and 2017. On May 2, 2020, Breitschmid e-mailed Olgiati stating he “had a $400,000 budget and wanted to build a house on a property located in Riner, Virginia.” Breitschmid asked Olgiati to create “rudimentary drawings” for a house, which Olgiati referred to as Manahoac House.

This partnership, however, was terminated two years later. Breitschmid said that he didn’t use Olgiati’s drawings because the building contractor “estimated the cost of Mr. Olgiati’s project to be more than double than the initial construction budget of $400,000. Therefore, all plans to build the Manahoac House ceased in spring of 2022.”

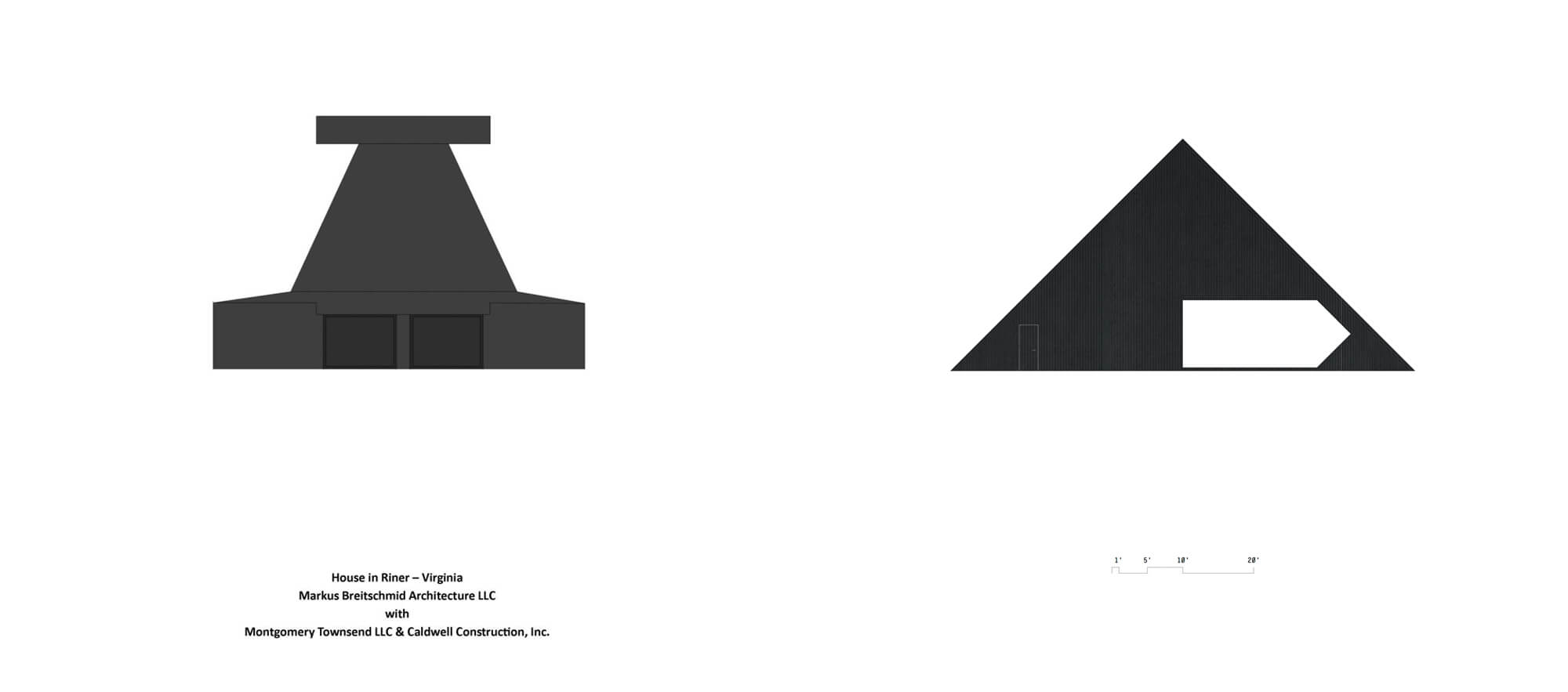

Breitschmid subsequently acquired the services of Montgomery + Townsend Architecture and Design—a Charlottesville, Virginia–based office—to work on a new plan. He hired Caldwell Construction to build the house designed by himself and Montgomery Townsend Architecture on the Riner site, albeit under a different name. “The Manahoac House does not [exist]. I can only say that no part of what is depicted on Mr. Olgiati’s schematic drawings of the Manahoac House was built,” Breitschmid said. He continued:

After the end of the collaboration between Mr. Olgiati and I, I designed a completely new project. The project that I designed and that has been built now has its own shape, dimensions, materials, structural concept, openings, site placement, room program, etc. Mr. Olgiati’s publicly stated claim that I executed ‘a distorted version of [his] design for the Manahoac House’ is false, without fact, and misleading. Any child who looks at the two projects could determine that they are completely different from each other (see drawings). It does not take some aesthetic judgment by a professional architecture critic to determine the otherness of the two. One could simply make an inventory of what is actually present such as shape and the qualities I have mentioned above to see the otherness.

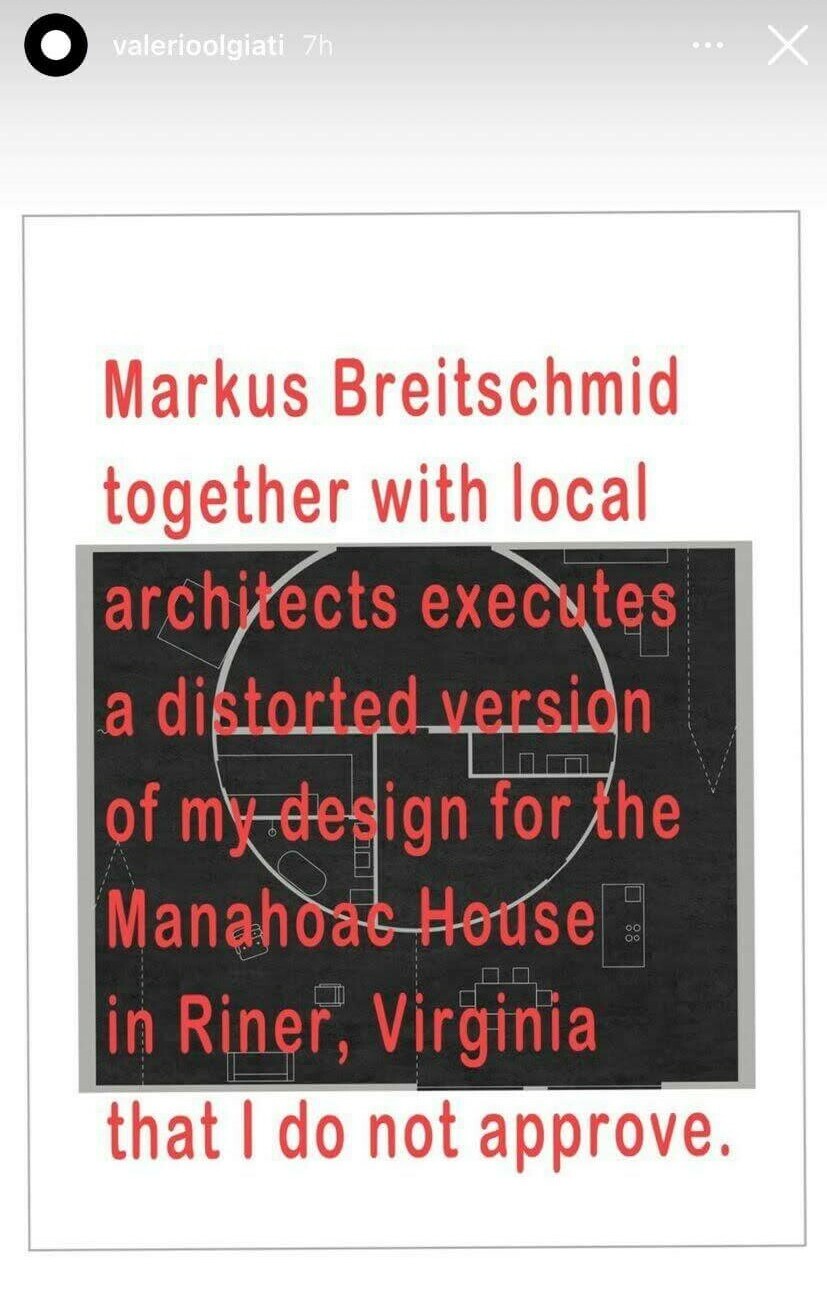

While Breitschmid’s iteration was under construction, Olgiati publicly commented that its design is a “distorted version” of his original drawings for Manahoac House. “Markus Breitschmid together with local architects executes a distorted version of my design for the Manahoac House in Riner, Virginia that I do not approve,” Olgiati said in an Instagram Story posted on August 13, 2022, when he had about 190,000 Instagram followers. Olgiati’s suit was filed in June 2023.

Breitschmid responded by filing claims for defamation and defamation per se. Olgiati then moved to dismiss the claims. In his defense, Olgiati claimed his social media post wasn’t actionable because it constituted a personal opinion that was not defamatory. Breitschmid’s defense countered by calling Olgiati’s statement “a verifiably false accusation,” and that the “tenor of the statement is one of accusation against Breitschmid.”

Olgiati’s motion to dismiss was granted on December 21, 2023, by U.S. District Judge Robert S. Ballou, who said that Olgiati’s Instagram Story “lacked the required sting to be actionable defamation” according to Nick Hurston’s reporting in Virginia Lawyers Weekly. “Stating that a person you collaborated with in designing a house negatively changed or ‘distorted’ your design and then built the ‘distorted version,’ which you don’t approve, falls short of an accusation of stealing or dishonesty, or an accusation that would similarly ‘render him infamous, odious, or ridiculous,” Ballou wrote in his opinion.

Ballou said that Breitschmid had “simply not pleaded facts to support his argument that readers would understand the statement as an accusation of stealing, with the requisite defamatory sting. Instead, a reader would understand Olgiati to be accusing Breitschmid of negatively changing Olgiati’s design, the design they collaborated on, and building a house that Olgiati dislikes.”

The crux of the debate came when jurors determined that claiming a design, building, or any artistic creation is a “distorted, improved, degraded, or enhanced version of another design, building or artistic creation” is a subjective statement based on the opinion of the speaker. Therefore, any such claim is regarded as personal opinion and is thus protected.

“A jury, like Olgiati, can have an opinion on whether the house is a ‘distorted version’ of Olgiati’s design; indeed, each juror is capable of having a different opinion,” Hurston reported. “Some jurors might think the house is totally distinct, others an improved version, still others might agree with Olgiati. However, these opinions are incapable of being proven true or false. Here, Olgiati’s Statement that the house is a ‘distorted version’ of his own design is not an accusation of stealing, it is an opinion, and unlike an accusation of stealing, the statement is not objectively verifiable.”

The initial dispute over service fees remains ongoing. As seen in the original filing, Olgiati sued Breitschmid in federal court for $360,000 in architecture fees, which constituted 90 percent of the total project budget of $400,000. Breitschmid said there was “never an agreement between Mr. Olgiati and I (e.g., AIA Document B104-2017), Mr. Olgiati’s provided services for the design of the Manahoac House did not even encompass fully what is listed under §3.2 Schematic Design Phase Services of the standard document (e.g., Olgiati never provided a “budget for the Cost of the Work” [§ 3.2.5.2]).”

He continued:

Mr. Olgiati was not a licensed and registered architect in the Commonwealth of Virginia when he tried to sell architectural services. If Mr. Olgiati now claims that he was providing regular architect’s services (and not a research collaboration like during the past 15 years), it has also been reckoned with the fact that—according to the Code of Virginia—an architect who intends to sell architecture services for a structurally unique house, such as the one Olgiati designed, is required to be licensed and registered in Virginia. Not unlike physicians and attorneys who practice illegally, for an architect not to be registered is a misdemeanor offense of the highest category. I do hope that this would interest such professional organizations as the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and other organizations such as DPOR or the Office of the Attorney General of Virginia (because Olgiati is not an American citizen). Mr. Olgiati’s claim against me ought to be dismissed by the court because it does not seem to be prudent to file a complaint that is based on an illegal activity of the complainant.

Breitschmid said he thinks the case will go until late August 2024. One of Olgiati’s lawyers told Virginia Lawyers Weekly that “part of Olgiati’s design—a very particular type of foundation like the base of a pyramid—had already been built when the architects’ relationship soured.” The article about this case is currently part of the Editors’ Picks section of the Virginia Lawyers Weekly website.

“We are still in litigation regarding this matter and we can not comment at this time,” a spokesperson shared via email when AN reached out to Olgiati for comment.