“My role was to make sure Mies could build the building he wanted to build.” Sixty-five years after the completion of the Seagram Building, Phyllis Lambert talks to Vladimir Belogolovsky about Mies van der Rohe, whom she selected to design it.

Vladimir Belogolovsky (VB): You happily lived in Paris for a couple of years until in 1954 you found out that your father, Samuel Bronfman, the owner of Montreal-based Distillers Corporation–Seagrams Limited, decided to build their expansion of the New York Offices on Park Avenue in Manhattan.

Phyllis Lambert (PL): In Paris, I had an apartment overlooking the Cimetière du Montparnasse where I painted. I didn’t take any classes. I just lived. I discovered food. I discovered all kinds of pleasures and I traveled in my tiny car everywhere.

There was a lot more business in America, so, naturally, my father wanted to build his building in New York. He knew I was interested in New York and in the project, so he sent me a letter with a picture of a design proposed by this firm, Pereira & Luckman, to commemorate the company’s 75th anniversary. I was appalled.

VB: In your book, Building Seagram, which I have right in front of me, you reprinted your multi-page response, protesting to your father. You wrote: “NO NO NO NO NO.” (the word “NO” was repeated five times) “I find nothing whatsoever commendable in this preliminary-as-it-may-be plan… You have a great responsibility and your building is not only for the people of your companies, it is much more for all people, in New York and the rest of the world.” What was his response to you after that?

PL: Oh, curiously, he told me that I could come and choose what kind of marble they were going to put on the ground floor. Of course, I was not going to do that! So, I went to New York. Immediately I got in touch with architectural critic Lewis Mumford. Then I spoke to Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, who told me to see Philip Johnson; he warned me that Philip was leaving the museum to start his own practice. So, I did. It was Philip who initially, over a weekend, invited Eero Saarinen and his wife, Aline Bernstein Saarinen, whom I knew from Vassar. So we discussed how to go about choosing an architect. Eero was a list-maker. He came up with three lists: those who could but shouldn’t, those who should but couldn’t, and finally, those who could and should.

The list of those who could and should had just Mies and Le Corbusier. There was some discussion about Frank Lloyd Wright. But by then I already realized that he belonged to another period and our project needed a new kind of energy.

VB: Who did you go to see from the other two lists—those who could but shouldn’t and those who should but couldn’t?

PL: Those who could but shouldn’t included Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and similar large commercial firms that were perfectly capable of designing an office building but not inventive. It was the second list of those who should but couldn’t that was interesting. From that list, I went to see Louis Kahn, Minoru Yamasaki, and Eero Saarinen, again. They were all very talented but not yet experienced architects. The list also included Marcel Breuer.

VB: I think there was also I. M. Pei. Did you go see him together with Johnson?

PL: I didn’t go see anyone with Philip. I went alone. I was not a child who needed a nanny! Where did you get that idea from?

VB: I think he mentioned in one of the interviews that he invited you and Pei for lunch at the Glass House. Johnson also mentioned in his interview with Bob Stern that he accompanied you to see architects but you went by yourself to see Mies.

PL: He is mistaken. Anyway, we may have gone for lunch with Pei but Philip did not go with me to see any of the architects when I interviewed them.

Let’s see. I did not see Le Corbusier. I didn’t think that a sculptural concrete building was appropriate for Park Avenue in New York City. The important thing is that when I went to see all these architects, all of them, in one way or another, mentioned Mies. They talked about their work in relation to Mies and how they would do their building differently. So, I realized that no one was doing anything as exciting as Mies then.

VB: Before we dive more into some of the details of making the building, I want to ask you about your father, Samuel Bronfman. What kind of a person was he and what was your relationship like?

PL: Well, there wasn’t much of a relationship, really. And before 1954, our contact had been minimal. My father was very much a hierarchy man. He wanted to build a dynasty. Well, as far as he was concerned, you don’t build dynasties with women. [Laughs.] So, my two younger brothers, Edgar and Charles, were in line to succeed our father. And the girls, my older sister, Minda and I, were supposed to get a good education, ideally in Switzerland, and marry wealthy men. OK? That was not exactly my idea of how I was going to live my life.

But when I came to New York from Paris and I was absolutely so sure and so passionate and clear about how wrong the building that he was planning to build was, he suddenly saw me for who I was.

VB: You have said, “Mies was about the essence of our time.” Could you touch on his character and a mission-like architecture?

PL: Mies said, “I am not doing architecture, I am doing a language.” He also said, if you are doing architecture you have to know what kind of a world you are living in.” To him, the world was structure and finance. He knew a great deal about materials which he learned from his father, a stonemason. He loved buildings in construction. He praised them for being marvelous and for revealing steel skeletons and “bold constructive thoughts.”

VB: How involved was your father in the design process in general?

PL: He told Mies and Philip that the building was to be their greatest work. I think there was only one condition my father made. Mies had a 1/8-inch scale model to study the plaza and the placement of a potential sculpture on the plaza. My father went to see the model and one thing he said was “Mies, I said I did not want a building on stilts.” To that Mies said, “But, Mr. Bronfman, look how beautiful it is.” My father looked and that was the end of the discussion! [Laughs.]

VB: He believed Mies just like that?

PL: Yes, absolutely! [Laughs.] They had tremendous respect for each other.

The plaza in front of the building came up from another consideration. Mies said that otherwise, in Manhattan, you can’t see a building from the street. He pushed the building back so you could see it. To me, the plaza is the most important part of the building. Much later, Mies said that the building would have been as good in steel as it is in bronze. So, it is not just about the building as an object. It is the plaza that makes it welcoming and approachable which is like an oasis amid the chaos of New York or the parvis before a cathedral.

VB: How many versions of the building did Mies design? Did he consider other possibilities?

PL: Mies always looked at possibilities. The hotel where he stayed in New York was within a short walk from the site. So, he walked around the site a lot. He would never suddenly say, “This is it!” The most important thing about Mies was his response to the facts.

I played the role of a connector between Seagram and the architect because I knew that if I didn’t, that building would never get built. Nobody understood what Mies was trying to do. The associate architects, Kahn & Jacobs, thought that Mies’s work was childish because it was so wonderfully simple! [Laughs.] People at Seagram had never heard of Mies before. They only knew of Frank Lloyd Wright and that his buildings leaked. On one occasion there was a brick firewall in the back for which Mies wanted to use bronze and the chairman said that no one would see it anyway. So, Mies said, “God would see it!” Of course, the building was very expensive, particularly because of the bronze.

VB: 1,500 tons of it, as reported by The New York Times at the time of construction.

PL: Something like that. Granite was also very expensive. But these are all materials that last, though the bronze needs to be cleaned every year with soap, water, and lemon oil to prevent discoloration due to the weather.

VB: Just to clarify, when we talk about bronze we talk about the bronze finish over brass, right?

PL: Where did you get this idea?! Of course not. Bronze comes in many types and colors and it all depends on the proportions of various metals. It is a metal alloy that consists primarily of copper and zinc with the addition of other metals and ingredients such as lead and tin. The question was: What do we need to produce, something strong or soft? So, it was a matter of the right percentage of copper versus zinc and other materials. Mies liked the result achieved. He likened it to an old penny.

VB: Your official role was the director of planning. Could you touch on that? And here I would like to insert your quote from the book you just mentioned. You said, “I was completely fearless!”

PL: Did I say that? [Laughs.] Well, I was. No, I wasn’t fearless because I had no fear! I wouldn’t know what fear was. I was so sure of my role. I used to go to the construction site and I thought that all around it no one knew what was happening. It was terrific. I knew we were building something great. I knew what was right and I knew what was not right. There is this wonderful thing about young people: they don’t know what they should or shouldn’t do. My role was to make sure Mies could build the building he wanted to build. I made sure of that and it happened.

For example, early on, the company had this idea that various distributors would have their names on the plaza’s pavement. So, there was a big meeting of all the heads of the company’s departments. My father was coming up with this or that suggestion. And after a short while, I just said quite firmly, “No.” I don’t think anyone ever said “No” to him before. But I simply could not hear them even discussing such a possibility. I am sure if I wasn’t there, they would go ahead and ruin every part of this beautiful building. So, my role was very important.

VB: The Seagram Building was sold in 1979 with many conditions of how it should be maintained. In other words, it was sold like a work of art. There was a series of restrictions, called Article 26 that protected not only the exterior enclosure but the first sixteen feet of the interior and all public surfaces and spaces by imposing strict maintenance specifications. How well is the building protected? I am curious because despite the landmark status of the Four Seasons Restaurant no longer exists and some works of art were removed.

PL: I was the one who suggested putting those Article 26 protection controls on the building, for which a special architect was hired to document everything thoroughly. And Seagram agreed even knowing that the controls meant a lower selling price. The first time the building was sold to the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America and everything worked very well. The second sale was fine until they decided to change the Four Seasons. The interior was protected but not everything that was in it. So, they took down a wonderful Pablo Picasso stage curtain, Le Tricorne painted for Diagilev’s Ballets Russes in 1919. It hung against a travertine wall in what was referred to as the “Picasso Alley” linking the restaurant’s two main column-free spaces, the Grill Room and the Pool Room. It was a perfect piece for that wall! Fantastic for its colors, tonalities, and size. But no, no, [Aby Rosen] said it was a rag. There are not that many things in New York that don’t change.

VB: Apart from planning the construction of the building you were also responsible for forming its art collection which was quite extensive. And you actually went to meet Picasso, as well as some other leading artists, right?

PL: It was great. I also wanted to discuss with him a potential sculpture for the plaza. He had in mind his Bathers, which I thought could be wonderful for the two pools in the plaza. Somehow the idea never went anywhere. Then I went to see Brancusi for the same reason. I can’t remember why that did not work out.

And then I thought that the great thing about the plaza is that it changes all the time, especially the way it is animated by people. So, I appointed a curator, Carla Ash, to curate exhibitions in the building and be responsible for temporary sculpture exhibitions at the plaza. Over the years we have shown major sculptures by Barnet Newman, Jean Dubuffet, Alexander Calder, Claes Oldenburg, and many others.

VB: What I find quite fascinating is that after your experience of building Seagram, you decided to study architecture, first by going to Yale and then transferring to IIT in Chicago to study under Mies.

PL: And in between those two schools I worked at his office.

VB: In other words, your roles flipped. You were his boss in New York and then he was your boss in Chicago.

PL: That’s right. [Laughs.] I went to Chicago to work at Mies’s office. He taught me his methodology; his logical way of looking at things and facts. Every Thursday I went to his house, sometimes with Dirk Lohan, his grandson, and sometimes with Gene Summers, who also worked at the office and who was Mies’s right man when we worked together on building Seagram. And sometimes, I went alone. We had dinners there and we always talked about architecture and our own projects, plans, and thoughts.

VB: What did you work on at Mies’s office then?

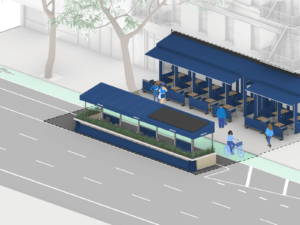

PL: On a little bank building, Home Federal Savings and Loan in downtown Des Moines, Iowa. It was built in 1962.

Vladimir Belogolovsky is the founder of the New York City–based Curatorial Project and author of Imagine Buildings Floating Like Clouds.