In 2018, Treviso, Italy–based architecture studio DEMOGO won second prize in the competition for an office and lab building in Bolzano, a northeastern Italian city. The design concept was based on the subtraction of mass from a monolithic urban block: an imaginary erosion that reveals the building’s interiors by turning its opaque steel skin into transparent glass surfaces. This excavation process generates a stepped sequence of floors, each with its own roof garden. The result was a beautiful and convincing structure with a strong urban form. A form so strong that it inspired another DEMOGO project from the same year: the new Regional Headquarters of Bologna’s Financial Guard (the Italian police force tasked with enforcing rules like taxation and customs), which was completed this past summer.

The project is the outcome of a gara—an Italian competition procedure for assigning public works in a quicker way than competitions. Gare, in fact, reduce the design submission to a scheme, letting the client concentrate on the financial feasibility of the project. Cost efficiency and conceptual clarity, in this sense, are the essence of gare, which is why DEMOGO’s winning scheme is defined by great rationality.

The core of the project is a stepped stack of four levels of office space (and as many roof gardens). Underneath the offices is a warehouse where the Financial Guard’s archives are kept. Closed to the public, the warehouse occupies the whole ground floor of the building, with the sole exception of a small entrance hall. A classical architectural composition is therefore slightly disturbed by the fact that the base contains an introverted service space rather than a magniloquent public foyer.

Despite being the programmatic core of the project, the offices are not the main event. They are simply designed according to current standards, regulations, and technologies. It is around them—in the connecting spaces, in the material fabric, and in the urban form of the building—that the architectural strength of DEMOGO’s project emerges.

The building rests on a triangular plot not far from Bologna’s Central Station. Each of the site’s three edges frames very different urban conditions: a dense residential block to the east, a social center occupying a former freight yard to the south, and a system of railway infrastructures to the north. The terraced shape of the building reacts to the complexity of the site and changes depending on where you stand. Its lowest height matches that of the neighboring building but grows taller toward the northern edge of the site, adjacent to the railway zone. This consideration of the surrounding urban conditions means the building subtly inserts itself into its plot while still becoming a visible urban landmark.

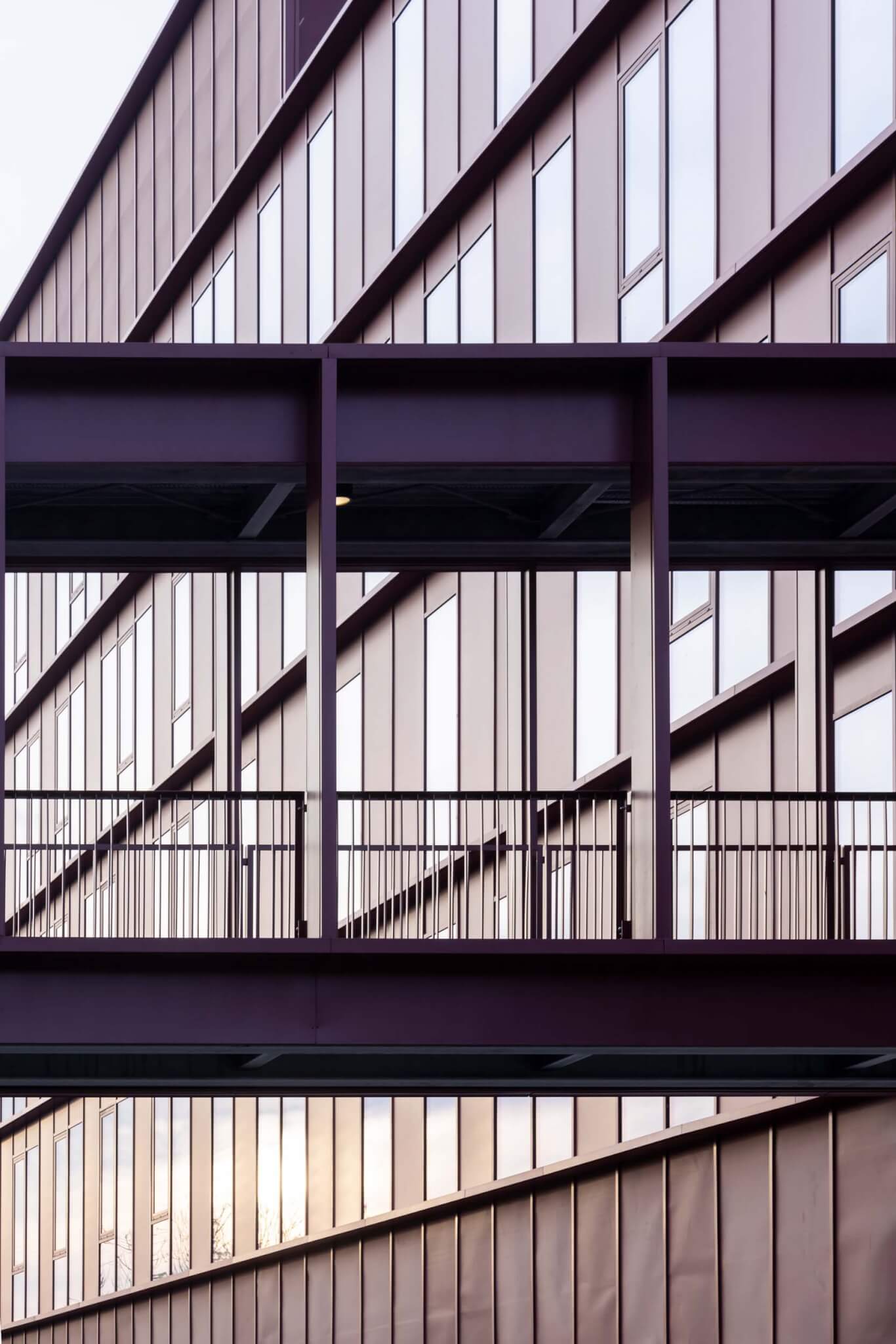

The rusty material of the railway reverberates with that of the building’s envelope. Supported by an exposed concrete skeleton, the facade is made up of modular, rhythmically composed 100-by-380-centimeter red steel panels. These balance the overall composition while hiding the technical infrastructure that runs on its external walls. The pattern is interrupted at each floor by a stringcourse, which produces a controlled play of vertical and horizontal lines and of thinner and thicker shadows. On the top floor, the facade is perforated to publicly declare the presence of the technical appliances behind it. Similarly, the facade opens farther to create a porch—and to reveal a hanging garden—on the first floor. The steel frames of the porch are thicker than they structurally need to be, so as to cast longer shadows. This compositional choice alters the perception of the building within and from the street.

By contrast, the gray plaster finish of the warehouse makes it look more like a basement, as if the building had been pulled out of the ground. But this departure comes as a surprise only to visitors and employees of the headquarters, considering that a perimeter wall hides it from public view.

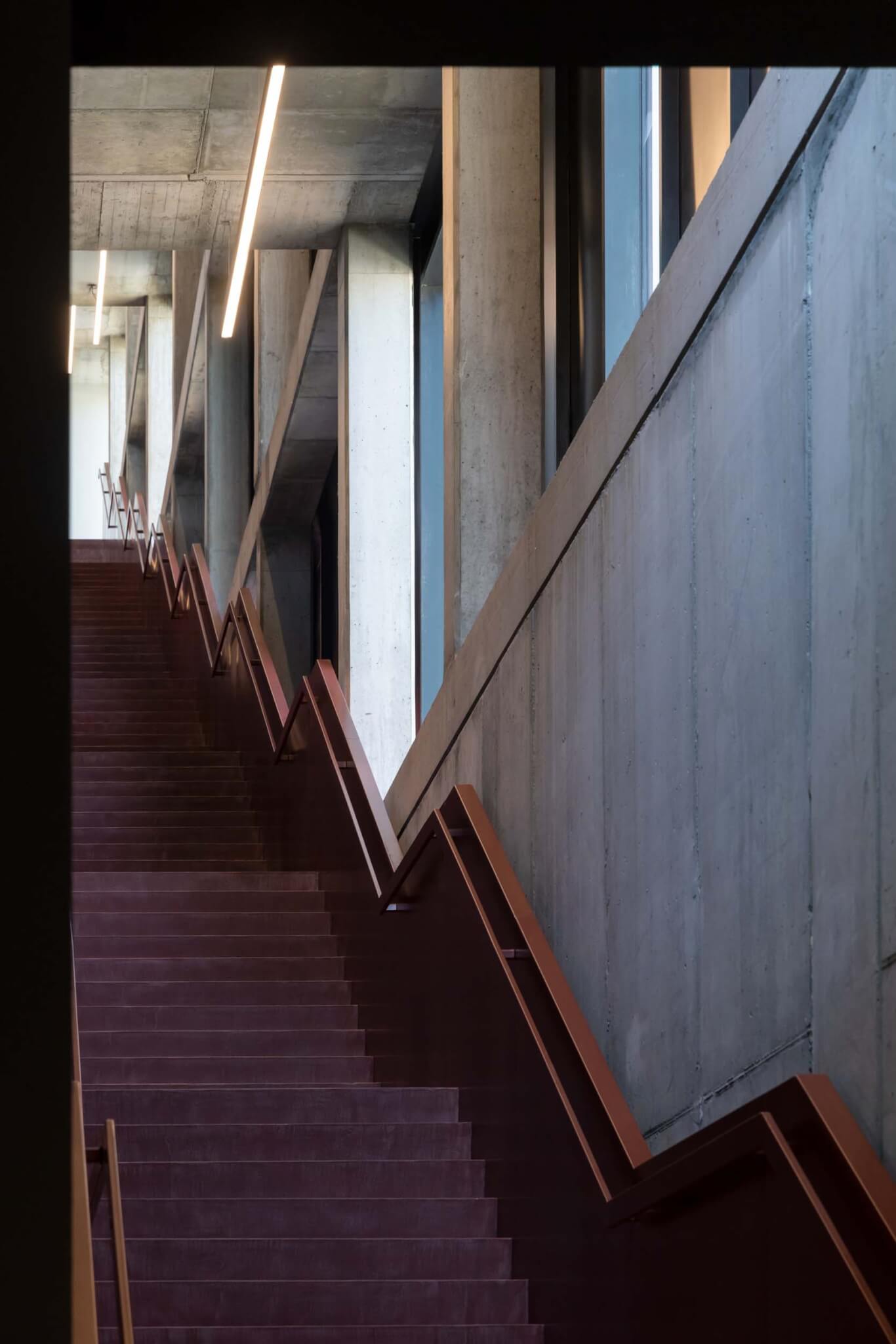

But the entrance, positioned directly under the hanging garden, generates anticipation for the most interesting feature of the project: a diagonal atrium generated by a scenographic staircase that extends all the way to the roof of the building. Besides connecting all the office levels and offering those who walk it a dynamic view of the surrounding urban landscape, this long sequence of red resin steps becomes the stage where Financial Guard employees can perform an unintended march every time they go to their offices—evoking the military character of the building through the ways they move through it. This kind of theatrical treatment of architecture is one of DEMOGO’s calling cards.

It is uncommon to find such spatial quality in recent Italian civic architecture, much less that built for the police. This is partly due to a scarcity of public investment in this building sector and partly to the way in which gare are conceived. Given that they already contain indications about the way in which the program should be organized, they generally limit an architect’s freedom to explore creative spatial solutions.

DEMOGO’s proposal for the headquarters of Bologna’s Financial Guard addressed this issue head-on. It openly criticized the original indications of the gara, suggesting a different and unrequested design approach. First tested on this project, DEMOGO’s strategy has proven successful, winning the firm five subsequent gare for the design of police buildings since 2019, as well as several more public competitions. This is good news. Not only for DEMOGO, which finds itself in the rare situation of being a small and emerging architectural practice working exclusively for public administrations, but also for Italian architecture in general. The soon-to-come enfilade of civic projects by DEMOGO might in fact reopen a once fertile field for architectural production, demonstrating that good design should not be confined to private clients.

Davide Tommaso Ferrando is an architecture critic, curator, and researcher interested in the intersections of architecture, cities, and media. He is currently a research fellow at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.