Out in Architecture was published in October of 2023 by a group of 24 coauthors and five co-editors: a team committed to uplifting the queer community in the AEC industry and creating “a house of joy.”

The book is comprised of reflections by LGBTQIA+ individuals within and adjacent to the field. It’s organized thematically by colors visible on the spine of the volume; these range from identity with and beyond practice to reclaiming space and redefining systems, and the forms move far beyond the traditional essay format. Poetry, prose, interviews, dreams, and reflections tell personal as well as universal stories.

In the words of Sarah Nelson-Woynicz, “Architecture is so personal, so political, and so much about identity, but we almost never talk about it that way.” So, Emily Conklin, AN’s managing editor, spoke with three of the publication’s editors, Sarah Nelson-Woynicz, Yiselle Santos Rivera, and Beau Frail, to talk about it this way and learn more about the process behind the book.

AN: How did this community of writers, editors, and designers come together?

Sarah Nelson-Woynicz (SNW): When we first started this project, I could count on two hands the number of LGBTQIA+ folks in architecture and design that I knew. But now, after publishing the book, these connections just keep expanding.

Yiselle Santos Rivera (YSR): We began by talking about visibility and how to build narratives that centered the LGBTQIA+ community. At that time, Sarah was thinking, “How do we create a platform for this?” And I had the thought: Why don’t we write a book? So we started meeting and assembled a team of editors. The skill sets in the group—the editors are all architects, designers, and creative people—were very complementary for the book project.

Beau Frail (BF): Everyone brought a unique skill set or what you might call their superpower to contribute toward the book’s reality. We were also intentional from the beginning about supporting the story each author wanted to tell.

YSR: I think my contribution was putting beautiful minds together and seeing them thrive. Beau does everything poetically and he brings an awareness about who we bring to the table; and Sarah is a phenomenal project manager, ensuring that things get done. I will confess that my thoughts run 1,000 miles a minute, so I was grateful that Beau and Sarah, as well as our other co-editors Amy Rosen and A. L. Hu, slowed the process down in an intentional and mindful way.

During our meetings we started by asking questions like “What does inclusion look like?” and “How do we create spaces that are safe?” This led to us building a community of queer storytellers. It began with people that we knew, though we recognized there were gaps in representation that needed to be part of the story. We were very intentional to bring in contributors representing a variety of ages, ethnicities, races, and genders as we sought to include more voices.

SNW: This book included 24 authors, and even post-publishing we’re all connected via email and checking in with each other regularly. Someone might share about something happening in their state halfway across the country, and then all of a sudden there’s a bunch of emails of support from authors saying, “We get it, we’ve gone through that.”

Now that the book is out, there’s even more room for us to take a step back and say, “Is the door wide open? Who else needs to be here? Who can we continue inviting in?”

AN: Can you tell me about the editing process, and how each story formed in the collection?

BF: Personal stories are powerful. We had various prompts as generative starting points, but a lot of people gravitated toward telling their personal stories because they knew it was important to create and share that for increased visibility.

The importance of creating a space where stories can’t be erased is foundational to Out in Architecture. I think another important outcome was deeply connecting with other queer architects. There wasn’t a directory or national movement connecting us yet. There have been local LGBTQIA+ Alliances established at AIA Chapters, which we built on to further connect the threads of solidarity between people who are marginalized because of their sex, gender identity, or orientation from across the country. The personal stories came out organically, as we encouraged people to show and not just tell their story.

SNW: We also had a few of the authors, in addition to the editors, involved in the editing process, or what we called “co-review.” That team included Landry Bado, Seb Choe, Chris Daemmrich, Amy Karn, Shristi Ojha, Larry Paschall, and Paloma Rdz. We uploaded everything to Google Docs and provided comments on each others’s stories. It was inspiring seeing people make comments like “Wow, you captured an experience that I also went through so well.”

AN: How did you land on a self-publishing process for Out in Architecture? What was your workflow like?

SNW: There was a lot of interest in ownership from the very beginning. When we started talking about the self-publishing route, that allowed us to really ask, “What do we want to make this?” And, “How do we want to make this different from other books that have been published?” We wanted to publish the book of course, but what was really happening was community creation. We know that there have been queer people in architecture for as long as architecture has been around. But especially recently, there has been an interest in creating ways for queer designers to come together in community.

YSR: Self-publishing is time consuming and challenging. We quickly recognized that there was a lack of access to funding or grants that could help us find an editor and a publisher, so there was a good amount of research into what form and route this book would take, which Sarah largely led. We originally thought of Amazon because it has everything embedded within it. But during conversations between the editors and authors, there was a lot of intentionality on recognizing which publishing spaces aligned with our values. We did not want to ask anybody to contribute money in addition to their time and energy to do this, but we wanted value alignment.

SNW: The three options are: Invest a lot of money but you don’t have to do extra work; invest no money, but it takes a lot of time route; and then the self-publishing route.

BF: With the self-publishing route we were able to weave deeper connections among our co-editors and co-authors. That’s the biggest takeaway: We got to design and build a house of joy, as we call it.

This way we also overcame the challenge of not already being connected with literary agents and publishers. This process allowed us to take all that energy we would have used to try to find the right publisher and instead put it toward building connections within our own community.

SNW: Knowing that we have a core group of people who are interested in being involved in and creating our own process makes me think: Of course we could self-publish Volume Two! We’ve built that community willing to invest their time and energy to do more than just write their story, which was already a huge investment.

AN: How is this book specific to, or specifically for, architects and designers?

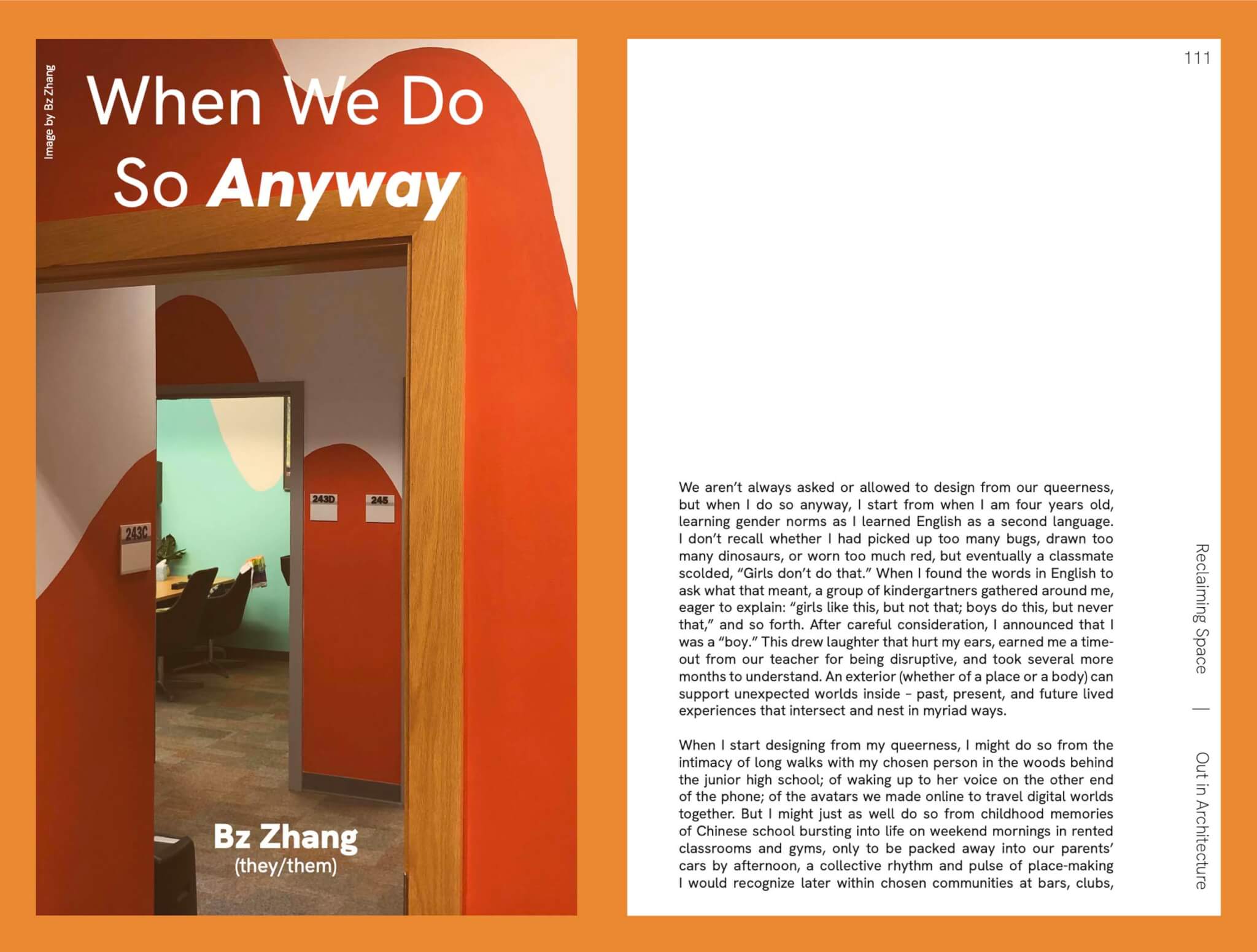

YSR: While we didn’t specifically require the storytelling to focus on the impact of the built environment, I think that lens naturally wove into the stories.

SNW: From the beginning, we didn’t want to prescribe the content or what the authors “had” to write. We started as a group of five co-editors asking ourselves, “What are we doing?” and “What is the purpose and our values?” And we started to see some of those questions emerge as themes informing what we were asking the authors to reflect on. These themes are: identity beyond practice, identity within practice, and reclaiming space and identity. Some contributions are related to the profession of architecture, but sometimes authors focused on their individual stories, who they are as a person and the journey toward their identity. Overall it’s about reclaiming space, whether it’s physical or representational, and also reclaiming and celebrating your identity.

Architecture is so personal, so political, and so much about identity, but we almost never talk about it that way. I’ve never really had the opportunity to experience and see my identity breathe life into my work, until now.

AN: What were some unexpected outcomes of the project?

YSR: The community-building aspect of this book. It has been the gift that will forever keep on giving. This is something that I imagined might happen, but never at this scale, and never with this level of intentionality. We got to know each other through this process in a much deeper way and faster than I expected. I’ve just never experienced that level of connection in other spaces.

SNW: The unexpected thing for me was everything that happened after “finishing” the book on October 11, 2023. You spend 370 days of your life thinking about something, living and breathing it with 24 other people. Then, all of a sudden, you launch it into the world for everybody. Publishing was just one part of the book’s life.

BF: For me, I keep coming back to how Yiselle talked about building a house of joy. I’m like, “Yeah, that’s what we’re doing!”

It’s also amazing to witness how expansive the word queer has become. It’s a definition for people who don’t fit into the status quo. Through the book, we’ve connected with people who are bending the binaries of all different forms of identity. The process of building solidarity between these expressions of identity has been really beautiful and eye-opening. The process really became about expressing our collective imagination. And we’re especially interested in how we can leverage imagination as a collective practice to design for just, liberated futures. Futures that we can bring our full selves into.

AN: Earlier you teased a volume two. Can you share anything about your vision?

YSR: I am going to drop my professional face and say that I’m crazy enough to share that we’re thinking about volume two already. We had some authors from volume one who were like, “We want to be a part of this when volume two comes around; what can we do?”

SNW: Right now we have a link to a Google form which is currently an open invitation for anybody who’s interested to share their name and email. And that’s not just for volume two, but also for a handful of other opportunities we’re envisioning, like having Out in Architecture come to your city for an event.

BF: We’re continuing to ask, “How can volume two be different, or more complete?” One of the ideas—which we’re excited about exploring—would be a volume focused on BIPOC architects who are also queer. We think that would be powerful. That would mean bringing in an editorial team who is entirely BIPOC and queer and editors like myself shifting roles to share what we learned and support the new team using this platform to tell their stories.

Beau Frail is an architect, artist, and poet living/working between Savannah and Austin at Fox Fox Studio and his own consulting practice, Activate Architecture.

Sarah Nelson-Woynicz is a storyteller and founder of Pride by Design, and architect with HKS living in Atlanta, Georgia.

Yiselle Santos Rivera is an activist architect, as well as a principal and global director of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion at HKS.