How to put everything great about New York into one building? Google has the answer. On Manhattan’s west side St. John’s Terminal, a forgotten relic of a bygone rail age is a building that quite literally built New York. As a rail terminal for the New York Central Railroad (now the High Line) the elevated tracks cut right through the building to drop off and load goods. Today, the building runs the city but in a different way: as a workspace for New York–based Googlers. A renovation by COOKFOX and Gensler has carefully rethought the groundscraper, from head to toe.

Work on the site started well before the internet giant signed on to occupy it, yet, “the building was generated by thinking, “‘What would a Google of the world fall in love with?’” Rick Cook, founding partner of COOKFOX told AN. COOKFOX worked on a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) for the site for Atlas Capital and Westbrook from 2013 to 2016. At this point, it was assumed that the building would serve multiple office tenants.

Oxford Properties purchased the building in 2018. Then in 2021, Google purchased the building after leasing it. With the tech company on board, the scope of the renovation somewhat changed, but what didn’t change were the principles for the workplace of the future: authenticity, flexibility and resiliency, and wellness.

One definition of authentic, coincidentally Merriam Webster’s 2023 Word of the Year, is “conforming to an original so as to reproduce essential features.” So, at St. John’s Terminal, the industrial history of the building had to be on full display. COOKFOX did exactly that, paying homage to the railway cut-through by evoking one of Cook’s architectural luminaries: Gordon Matta Clark, king of the “building cut.”

The exposed rail beds were the first salvaged component of the massive building, and guided by the ethos of saving as much as possible, the architects restored the masonry facade, limestone detailing, and the hefty base of the building. (A life cycle analysis estimates a savings of 78,400 metric tons of carbon dioxide by opting to save the structural foundation.) Additionally, the building cores were constructed with a new technology called precast post-tension bridge construction. This allowed for faster work while saving on transport and embodied carbon, as the adjacent north site was used as a staging ground for the large precast concrete core elements.

Standing in front of St. John’s Terminal today, one counts 12 stories with setbacks at the fourth, tenth, and twelfth floors. But in 1934, the building topped out at just three stories. In the 1960s a fourth floor was added, but “it wasn’t the same quality as the first three floors” Cook explained. The architects removed the shoddy fourth floor to return the structure to its original massing before adding a new volume on top.

Given its hulking appearance alone, it’s evident the base of the now 12-story structure was well-built; it had to be able to support the enormous loads of the trains. COOKFOX harnessed its burly stature when considering the new addition.

“We found out that we could actually bear the entire weight of the building onto the existing superstructure and the existing caisson foundations,” Cook shared.

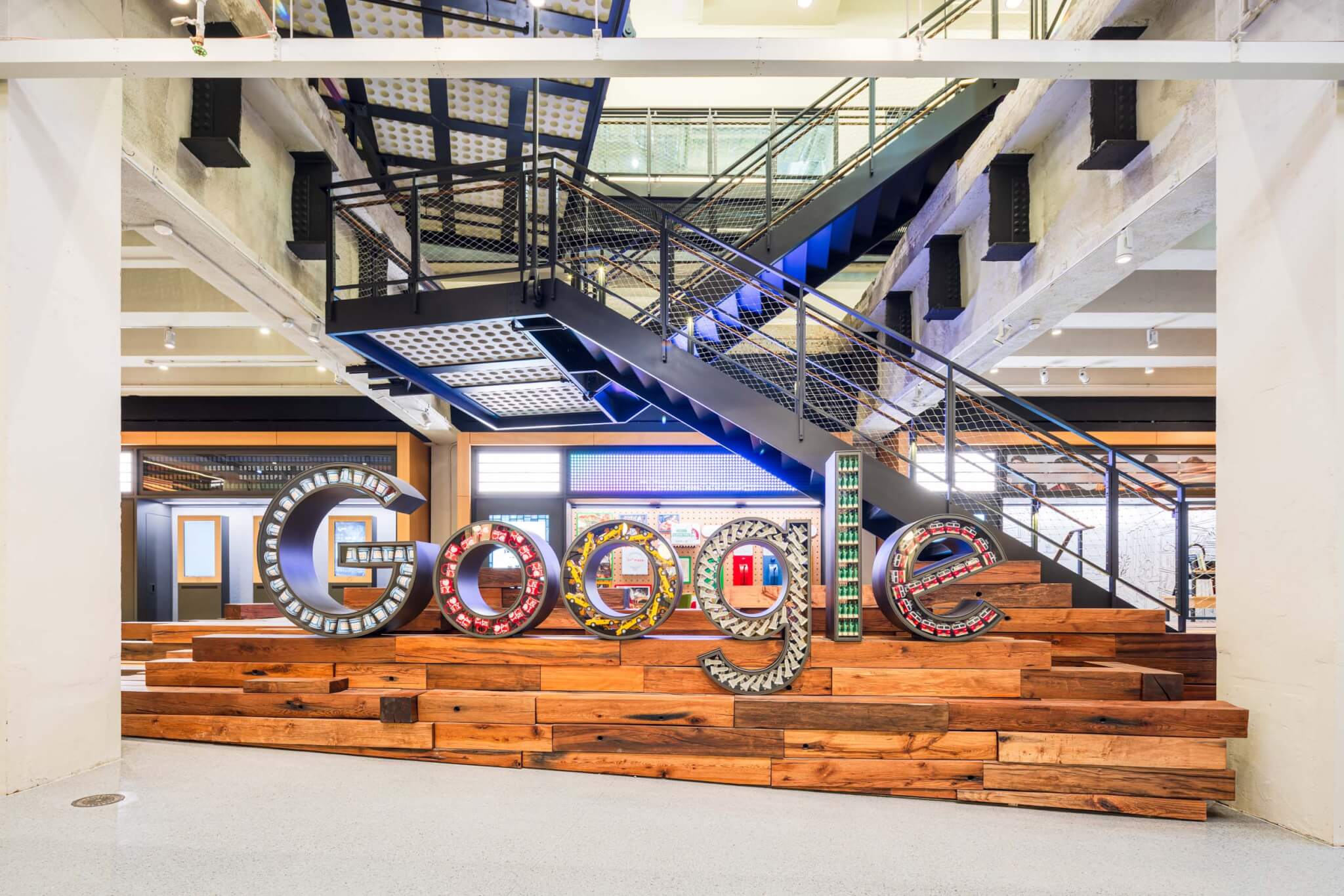

Working with a building with such large floor plates warrants thinking of space as an urban planner would. Circulation is conceived similar to that of streets and avenues—long and wide passageways and emulating the concept of neighborhoods. At an opening event for the building, Google leaned into its New York origin story: Speeches from Google executives and New York legislators reminded (or educated) attendees that Google was once a one-man operation working out of a coffee shop on the Upper West Side.

“What they wanted to do was to create something that set the presence of Google in New York City, and they wanted the building to be authentically New York,” said Carlos Martínez, co-managing director of Gensler’s New York office, which worked on the interiors of the project. “That’s where we started creating this idea of telling the story of relevance and historical impact, especially around the history of Manhattan.”

Symbols of New York overfill the space, from the ubiquitous Greek diner coffee cup to its use of taxi cab yellow. More subtle references to the city also permeate: meeting rooms are named for native tree species and the exterior of the theater dons Guastavino tile.

What else do New Yorker’s love? Being outside.

“In New York City, our parks are our third spaces. Every city kind of has a version of what that is, and we did a study where we analyzed this. In London it’s the pubs, in Brazil it’s the barber shops, while in New York it’s our public parks,” Martínez said.

Drawing natural elements into St. John’s Terminal was important to Google because its 111 Eighth Avenue office had sparse opportunities to greet nature given its density and location.

“We talked about the fact that the building needed to have visual porosity, where you can see in and then where the building gives back to the city,” Martínez said.

This porosity is apparent walking along Washington Street, where the greenery spills out from the fourth-floor setback. The entrance along West Houston Street is more park-like than traditional office entry plazas: a winding bike path models itself after trails and benches are formed with rocks.

“My little soundbite is, my favorite part of the building is that it feels like we were able to bring Hudson River Park one block further inland,” Cook said.

Up on the 12th floor, a walking lap was realized around the perimeter, so one doesn’t even have to leave the building to experience a connection to the outdoors. All the landscaped surfaces were planted first before the locations of pathways or seating were considered, in a move away from traditional approaches to landscaping. Future Green Studio was the landscape designer for the project.

Beyond excess greenery and riverfront views, the building leans into that nature connection in other ways. On the ground floor, jagged tilework maps the original Manhattan shoreline that ran through the building and a Manhattanhenge moment occurs each year on the summer solstice when the sunset perfectly aligns in the stairway.

The ethos of a neighborhood as a place with a shared, distinguished character is evident in the communal office spaces where large tables foster connection and interaction with colleagues. In the a 417-seat theater, colored upholstery carves out sections within the venue to scale to the programming needs. Smaller meeting rooms have their own visual identity, too: in one, objects found in taxi cabs are painted yellow, an inventive decorative feature that doubles as a statement wall and a game of I-Spy.

There is familiarity at every corner, a déjà vu experience, a shared nostalgia for the long-gone and lived-through. You know your neighbors and there is a distinctive character that evokes a sense of belonging.

It’s New York or nowhere.

Project Specifications

- Design architect: COOKFOX Architects

- Site developer: Oxford Properties

- Architect of record: Adamson Associates

- Civil engineer: Phillip Habib & Associates

- General contractor: Turner Construction

- Landscape design: Future Green Studio

- Lead interior architect and designer: Gensler

- General contractor: Structure Tone, Turner

- Landscape architect of record: Langan Engineering and Environmental Services

- Lighting: Castelli Design, Fisher Marantz Stone, Lightswitch, Lighting Workshop, L’Observatoire International, Lumen Architecture