Perched above historic Stuyvesant Square Park is Friends Seminary, one of New York’s most prestigious K–12 schools, founded in 1786 by Quakers. There, the world famous artist James Turrell has completed his newest architectural intervention, Leading. The art piece is a deeply personal one for Turrell, a fellow Quaker, and marks a full circle in his long career. Leading’s aesthetic and ethereal qualities can be traced back to Turrell’s own spiritual beliefs, and tenure as an environmental justice activist.

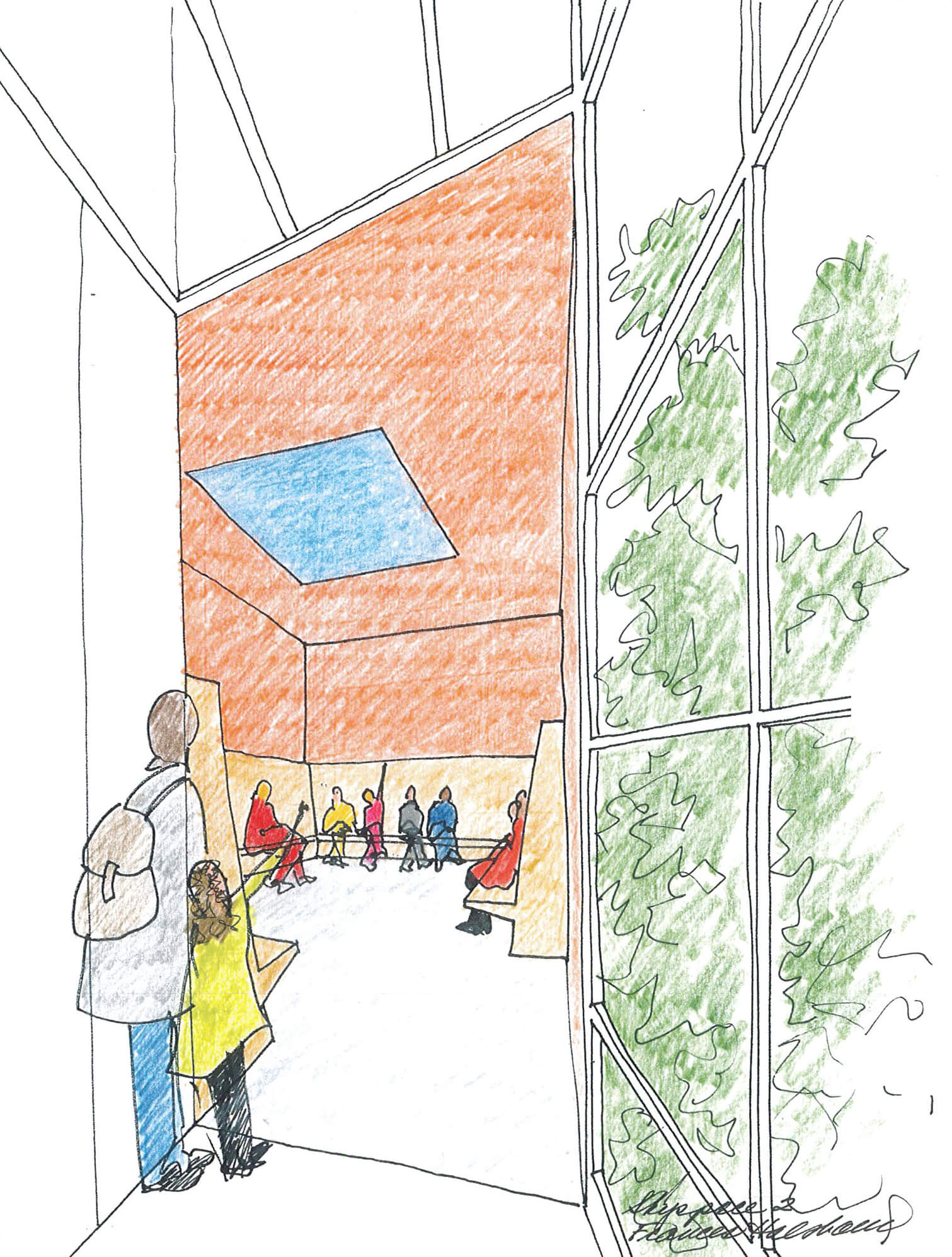

Leading is one of more than 85 Skyspaces by Turrell since his career took off in the 1960s. Frances Halsband, founder of Kliment Halsband Architects, a Perkins Eastman Studio, was the design architect.

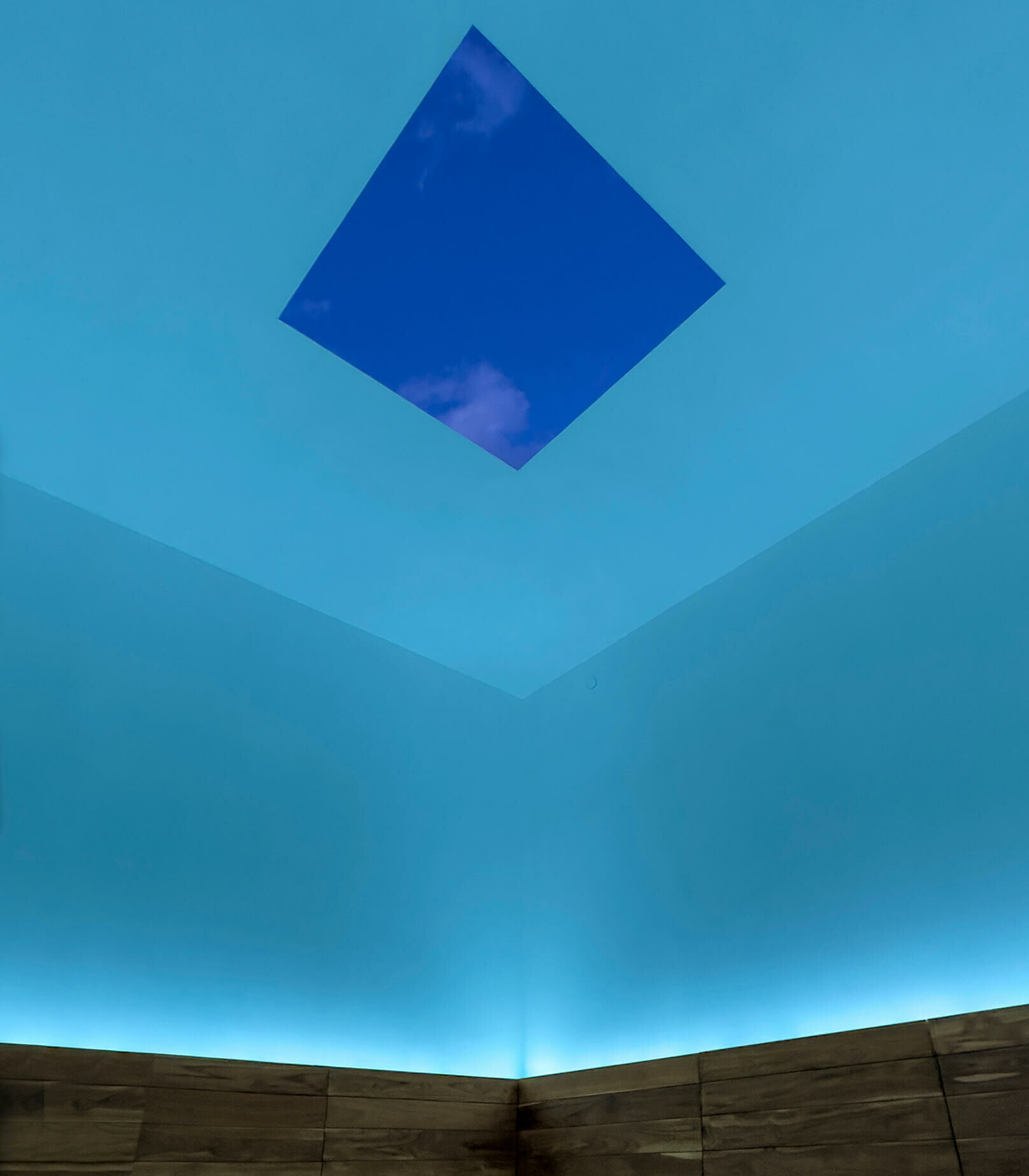

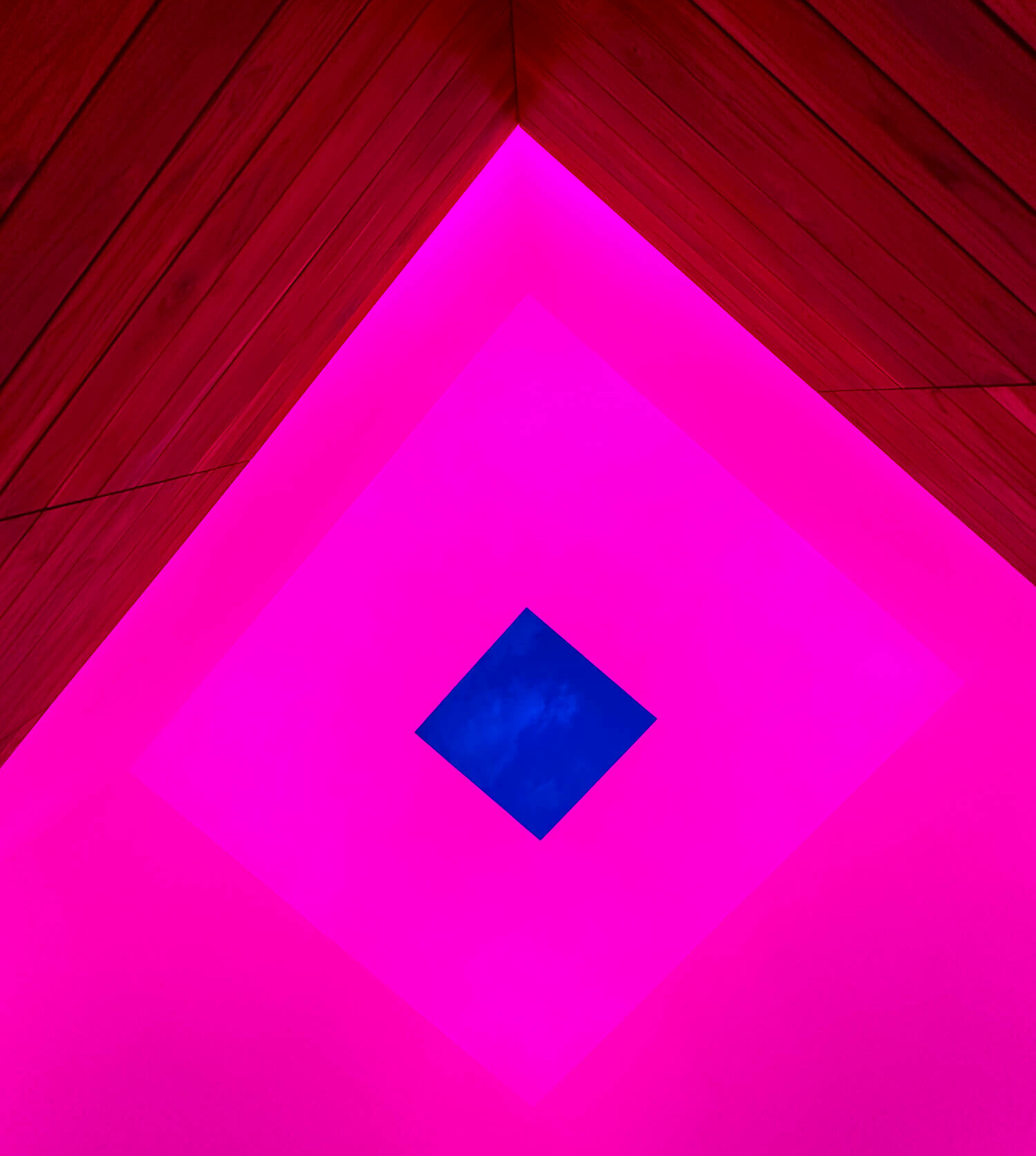

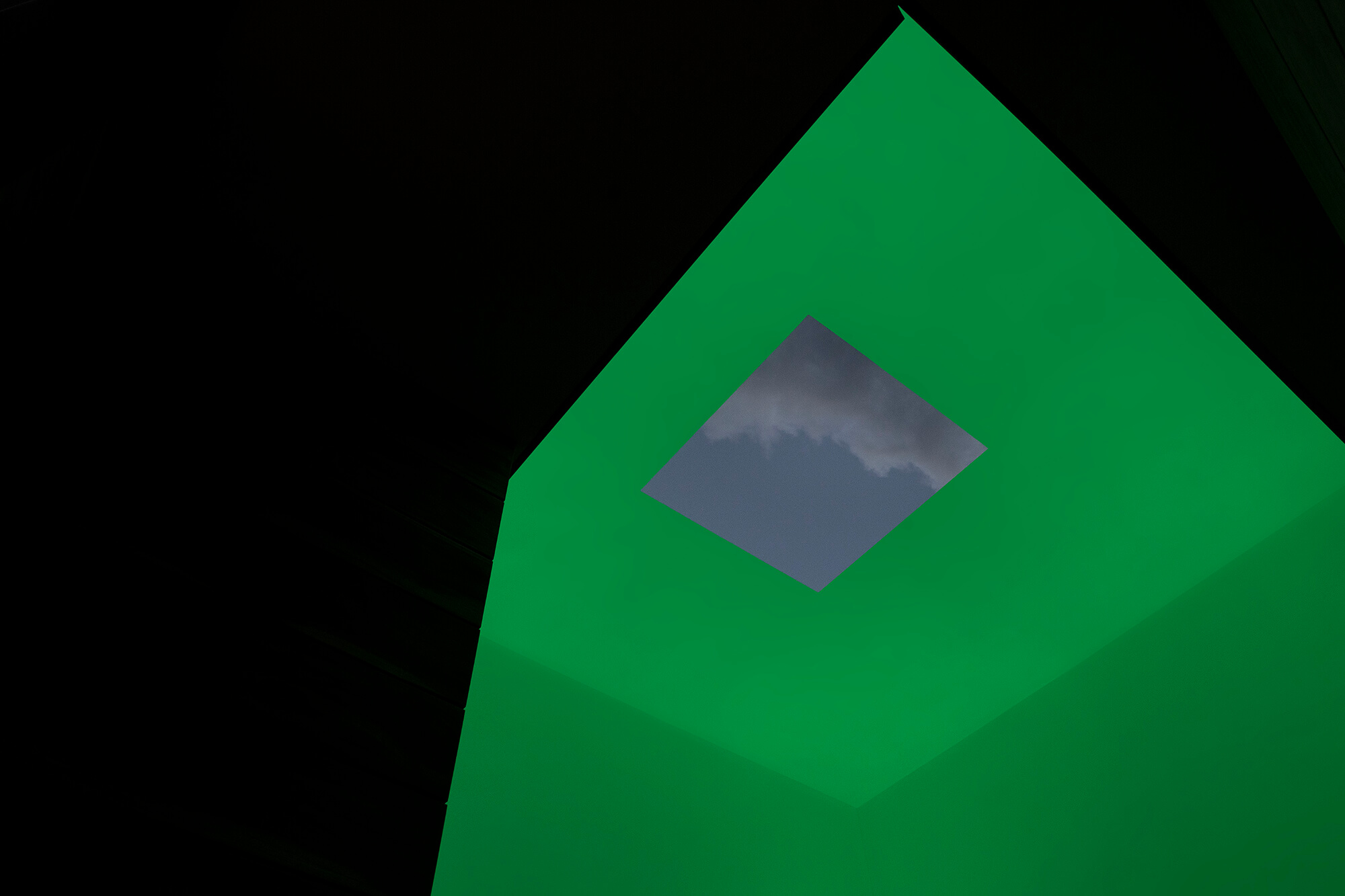

The 20-foot by 22-foot room invites visitors to gather underneath an awe-inspiring oculus that changes colors. At certain intervals, the room changes from somber blue to tangerine orange, and then to lime green, powder yellow, and sublime purple. Visitors are encouraged to lie down on soft, teak benches, take a deep breath, and look up. Such spaces perform well for young children, particularly neurodiverse students that are hyper-sensitive to space, and light. On sunny days, the oculus opens up to the heavens vis-a-vis a retractable roof, framing the clouds as though they too are masterpieces. Through the aperture, an airplane appears on its way to JFK, leaving behind a contrail, which reminds the students that they live in modernity, and of the rising tides of global warming.

Friends Seminary has changed quite a bit since it first opened in 1786. The urban campus’s spiritual center is the 15th Street Meeting House, a pitched-roof, red-brick building from 1864 designed by Charles T. Bunting, a Quaker architect. Upon entry, visitors are transported into a historic lobby that demonstrates Quaker values: Posters adorn the walls of young activists at environmental justice rallies, and even maps that show the location of every U.S. military base on earth. Peace Week at Friends Seminary has just ended, where faculty and students of all ages discussed the military-industrial complex, and the Quaker people’s commitment to social justice more broadly.

A luminous, multi-story congregation hall just beyond the lobby exists that’s lined with red velvet benches, white walls, and scant crown molding. Quakers eschew depictions of God, an aesthetic practice which manifests in the meeting hall’s spartan ornamentation: No stained glass, no statues, or even lecterns. This iconoclastic absence is meant to create a direct, unmediated connection between believers and their creator, encouraging them to find their own “inner light.” The hall is squarish in plan. Speakers orate from the middle of the room, not the front, to break down the hierarchy between lecturers and their audience, creating a more democratic milieu.

Not so long ago, James Turrell delivered powerful sermons in the 15th Street Meeting House about environmental and social justice. Turrell used to be a congregation member there before he moved to Arizona. It was while living in Gramercy Park where Turrell befriended Robert “Bo” Lauder, Friends Seminary’s Head of School. Leading at Friends Seminary is the culmination of Bo and Turrell’s enduring friendship.

Thus, Leading is a work of contemporary art deeply rooted in Quaker aesthetics and values. Compositionally, Leading’s oculus is emblazoned onto the ceiling like Kazimir Malevych’s Black Square, but its colors evoke the abstract studies of Josef Albers. Spatially, it has all of the characteristics of traditional Quaker meeting houses dating back to the 1800s, namely how viewers sit across from one another in a square, an ideal plan for genuflection and horizontal discussion.

Leading marks the end of a series of renovations at Friends Seminary by Kliment Halsband Architects that started in 2014. That year, Friends Seminary officials acquired properties surrounding their homebase, namely three Italianate 19th-century homes, and the 1960s-era Hunter Hall. After, Kliment Halsband Architects was brought on to stitch the old and new buildings together, and expand Friends Seminary’s footprint. The renovation delivered two additional stories atop Hunter Hall, giving Friends Seminary more classroom space, and even surface area for a greenhouse.

After the design process kicked off, Bo Lauder rang his old friend Turrell in Arizona with a proposition for an artwork somewhere on campus grounds. Then after Turrell toured Friends Seminary and saw the unobstructed views its new rooftop provided, he had an idea. Turrell proceeded to work with Kliment Halsband Architects on designing a steeple on the top floor of Friends Seminary, replete with all the technical gadgets needed to make such an optically magical space function. Lauder started a capital campaign that raised $3.9 million to build the Turrell installation, which the artist designed pro bono. Turrell even donated one of his holograms to sell at auction at Christies, raising $187,500 for the effort.

Early on in the artistic process, the designers hit a snag. At first, the Turrell installation was a bit too tall: The height that he and Halsband arrived at for Leading was higher than what the building code allowed. So the artists went back to the drawing board and eventually came up with a creative solution. They convinced the city planning commission that the new space was a “house of worship,” thus eligible for a zoning override, by presenting it as though it were a steeple.

“I remember sitting with our lawyers asking ourselves, ‘What should we do? It’s too tall!’,” Halsband told AN. “Eventually, someone on our team said ‘Hey, wait a minute!’ and told us about a loophole. In New York, church steeples are allowed to get away with height variances. So we were able to go back to the zoning board and discuss how the space is related to Quaker beliefs.”

Halsband has long worked with famous artists, including close collaborations with Maya Lin. Working with Turrell, she said, was seamless and wonderful. “Before our first meeting with James, we read all of his books. We were nervous at first, but he was so approachable when we first met. James is like the best kind of engineer to work with.”

After the team assembled, Halsband worked with Turrell and Ryan Pike, the artist’s lighting designer, to perfect the details. Turrell meticulously designed the angled teak seating so as to provide an optimum, comfortable experience. They also designed the lip of the oculus so that viewers don’t see the depth of the slab, a visual effect made possible by a precast knife edge. “Turrell wanted the room to be dimensionless,” Halsband said. “And that’s the magic of it. The sky just drops into the room, unframed. It just drops in.”

Leading is the second project by Turrell predicated on his faith as a Quaker. Twenty-three years ago in Houston, Turrell completed a Skyspace for the Live Oak Friends Meeting Hall. In New York, Turrell has built similar interventions at the Guggenheim and MoMA PS1. Susan Morris, a local filmmaker, has followed Turrell’s work for years. “It’s a much more intimate space than his past works,” Morris told AN. “In other spaces, you don’t realize as much how the colors change from one to another, but here, the change happens before your eyes. Also the wood inside is slightly angled which gives it a different experience. The result is a much smaller, private space. And also the fact that this is for young students gives the space a different spin.”

Today, Turrell, now age 80, lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, but has no plans of slowing down. Since 1979, he’s been working on a massive work of land art, Roden Crater, which he expects to soon finish. Roden Crater occupies a volcanic cinder cone in northern Arizona’s Painted Desert region, proffering a gargantuan beam of earth that rises up from the desert. The work represents Turrell’s magnum opus, and upon completion, will function as an active observatory for scientists that study the cosmos.

And who knows? Perhaps someday, one of those giddy school children at Friends Seminary, mouth agape staring in awe through Turrell’s oculus on Stuyvesant Square Park, will be one of those explorers at Roden Crater, embarking on the world’s next great scientific discovery.

Leading is open for public viewing on select Fridays.