The State of Housing Design | Edited by Joint Center for Housing Studies | $30.00

There’s a surefire way to rile up a neighborhood: just talk about housing. It seems like there’s general consensus that cities need to build more, but when it comes to figuring out how and where to do this, battle lines come into sharp relief. Is the culprit restrictive laws? Greedy developers? Xenophobic communities? Outdated building techniques? The wrong types of structures? The answer is, well, all of this. But also so much more. What we’re seeing today—a shortage of several million homes—is the result of a decades-long crisis of federal, state, and local policy on everything from land use to lending.

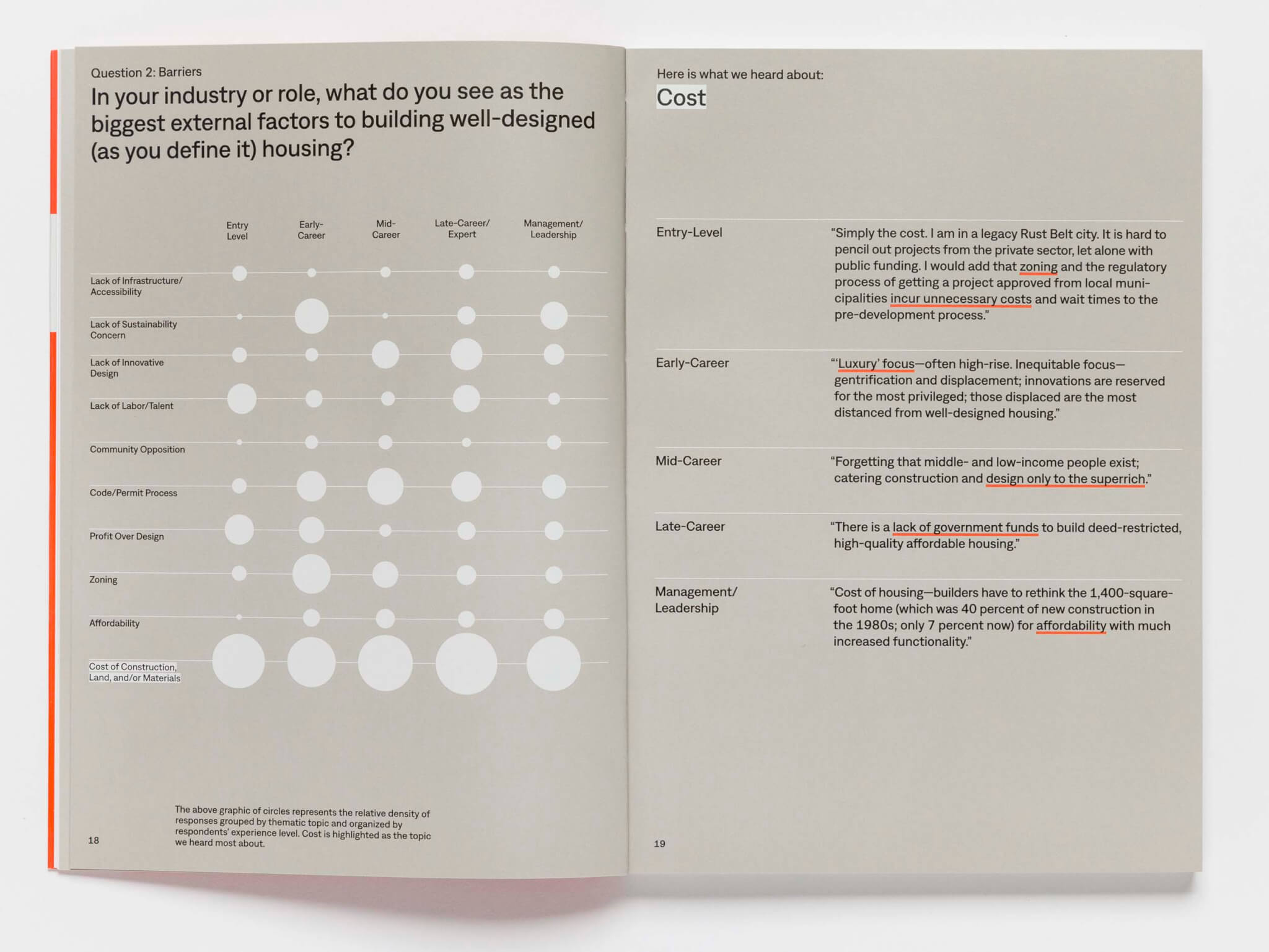

It’s easy to feel defeated by the American housing system’s dysfunction. But The State of Housing Design, a book that the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard (JCHS) published in October last year, shows how new architecture is grappling with these realities. The book is based on a survey of 1,300 practitioners who shared the trends they’re seeing, the common roadblocks they’re encountering, and their thoughts on what’s most important in the industry today. It features 113 projects—discussed across 25 essays and interstitials—that speak to these themes. Some of them include building density, water and energy efficiency, rehabilitating old buildings into something more useful, creative financing, and experimenting with new materials. These attributes show up in developments spanning a $350-a-month apartment in a San Francisco Bay Area exurb (that would be Stonegate Village, by Self-Help Enterprises) to a $3.75 million condo in Brooklyn (SO – IL’s multi-family project 450 Warren) and everything between. While the JCHS has published an annual report about the real estate market for 35 years, this is the first time it has examined the physical form of housing that responds to the problems outlined in those reports.

These case studies are meant to be read with optimism—to “uplift understanding and appreciation of the critical role design plays in addressing the nation’s housing challenges,” wrote Chris Herbert, the managing director of the JCHS. I agree that the wins should be celebrated: All the projects are beautiful. They fulfill a variety of needs. They are environmentally sensitive. Many are affordable. But overall, the tales of success come across as bittersweet.

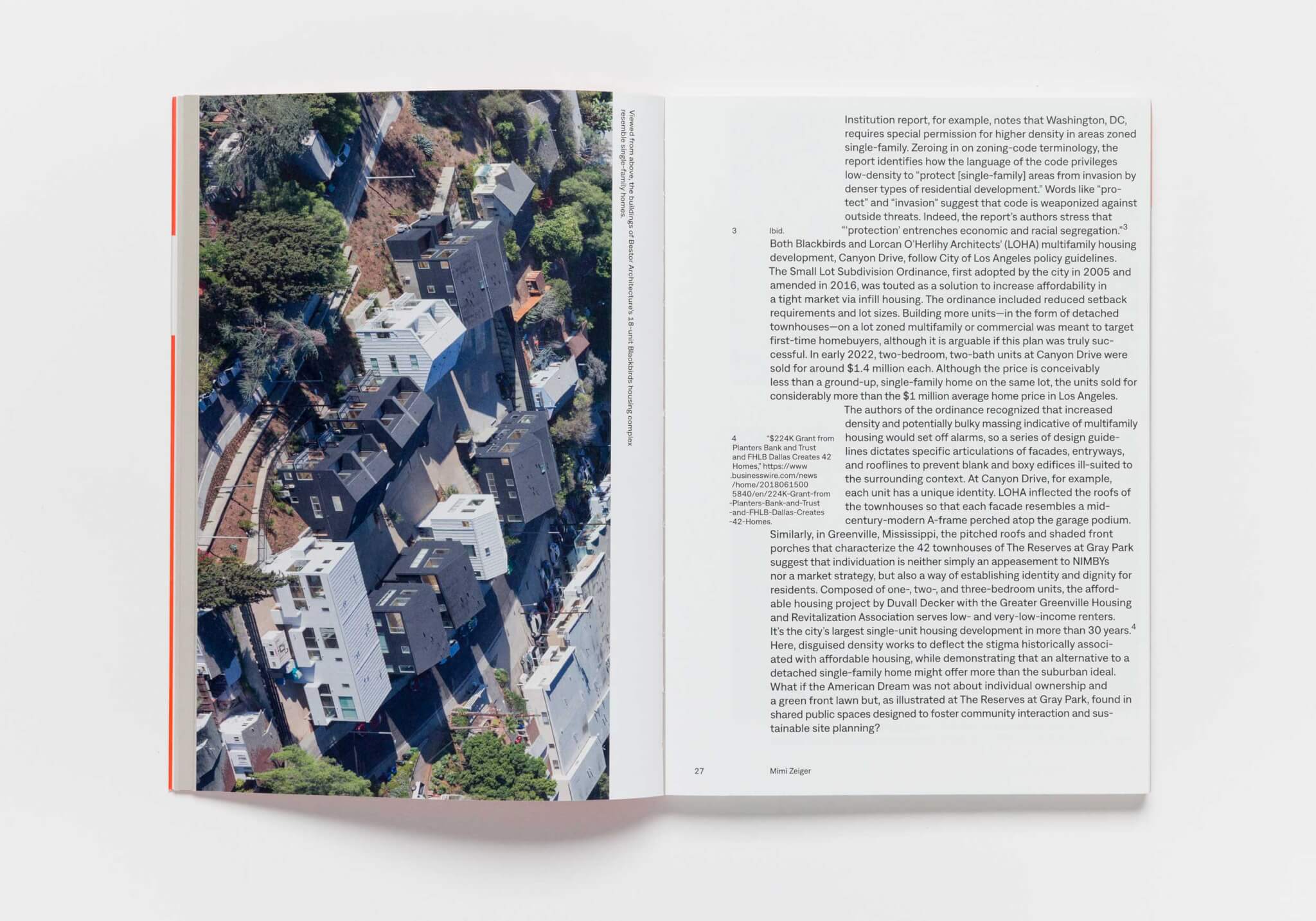

Throughout the book, there’s a sense that the architects and developers are getting away with something; that they’ve maneuvered through an obstacle course of astronomical construction costs, time-exhaustive permitting, Byzantine codes, and inexorable NIMBYs and managed to build something necessary and good. They’ve applied for variances and said the right things in public meetings to push a project through. As critic Mimi Zeiger wrote in “Disguised Density”—an essay about multifamily developments in Los Angeles that are positioned as “gentle” or “stealthy,” like Barbara Bestor’s Blackbirds project—much of the creative language around trying something different “underlines the long-held entitlement of home ownership and bias of single-family zoning.” In other words, the root challenge is confronting deeply entrenched cultural beliefs that housing is an investment. The case studies, as compelling as they are, are reminders that architecture is not policy and that unless policy changes, the state of housing design will be a few glimmers in an otherwise muddy landscape.

The book’s editors list several caveats regarding project selection and framing, for example that it “tends to ignore” and is “admittedly quiet” about the case studies’ political context, the process of actually getting these projects built, who benefits financially, and what might have been constructed instead. Most of the essays don’t address money directly, including the price residents pay to buy or rent these projects and profit margins for the designers and developers. I craved the granularity of dollars and cents. However, the case studies that do make a point to talk about these line items are the most revealing. In his essay on community-led development, writer Stephen Zacks describes how a nonprofit housing developer in Santa Fe applied for federal tax credits three times before getting approval, delaying a project for years, and how he required six different funding sources. Meanwhile, a Southern California affordable housing developer told him that waiting lists for his 50-unit projects are 1,500 people deep. Can design alone ever meaningfully address this widening chasm between supply and demand?

The book is compelling, accessible, and journalistic in nature. It could be passed around a city council meeting, distributed to community groups, and routed to senators. For designers and developers who want to learn from their peers and have the grit to endure headwinds, there are useful lessons about navigating bureaucracy. However, the book’s strongest argument is in its subtext: that everyone in the industry is confronting entangled issues. In the afterword, Harvard professor Farshid Moussavi wrote that the projects “demonstrate how designers can take a proactive approach to the crisis.” How powerful could it be if this book led to solidarity among progressive architects, designers, and developers? It might compel us to engage politically so the work changes systems instead of responding to them.

Diana Budds is a New York–based writer covering design and the built environment.