On British Columbia’s Vancouver Island, ZGF and Parkin Architects—a Canadian firm with offices in Toronto, Ottawa, and Vancouver—are designing a hospital that could set a new standard for culturally inclusive healthcare design. Cowichan District Hospital in Duncan, British Columbia is a $1.45 billion project that leverages evidence-based design to foreground Indigenous people’s healthcare needs.

Upon completion, the 607,600-square-foot facility will have patient rooms equipped for Indigenous healing customs that involve burning, and other cultural amenities that resulted from close dialogue with Cowichan Valley’s First Nation communities. Parkin is the project’s prime architect, and ZGF is leading shell and core design.

In Canada, socioeconomic disparities between First Nation communities and white Canadians are staggering. Today, 25 percent of Indigenous people (Aboriginal, Métis, and Inuit) live below the poverty line, as reported by the Canadian Poverty Institute, and Indigenous women make up 40 percent of Canada’s prison population.

Such inequities manifest in Canada’s healthcare system as well. A recent survey conducted by the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre in Winnipeg found that Indigenous youths (age 19 to 29) and their families get lower-quality healthcare at Canadian hospitals than white Canadians. The report showed rampant “anti-Indigenous discrimination” against First Nation communities and a “deep mistrust” of the healthcare system overall.

The antidote, respondents said, was more Indigenous staff, trauma-informed care, Indigenous-led addiction clinics; and culturally inclusive hospitals replete with features like patient rooms equipped for healing customs, Indigenous food prep kitchens, art programs, and gardens.

To help meet this important demand, Parkin Architects and ZGF rose to the occasion. The forthcoming Cowichan District Hospital will replace an existing 20th century building on Vancouver Island, built on the unceded traditional territory of Cowichan Tribes.

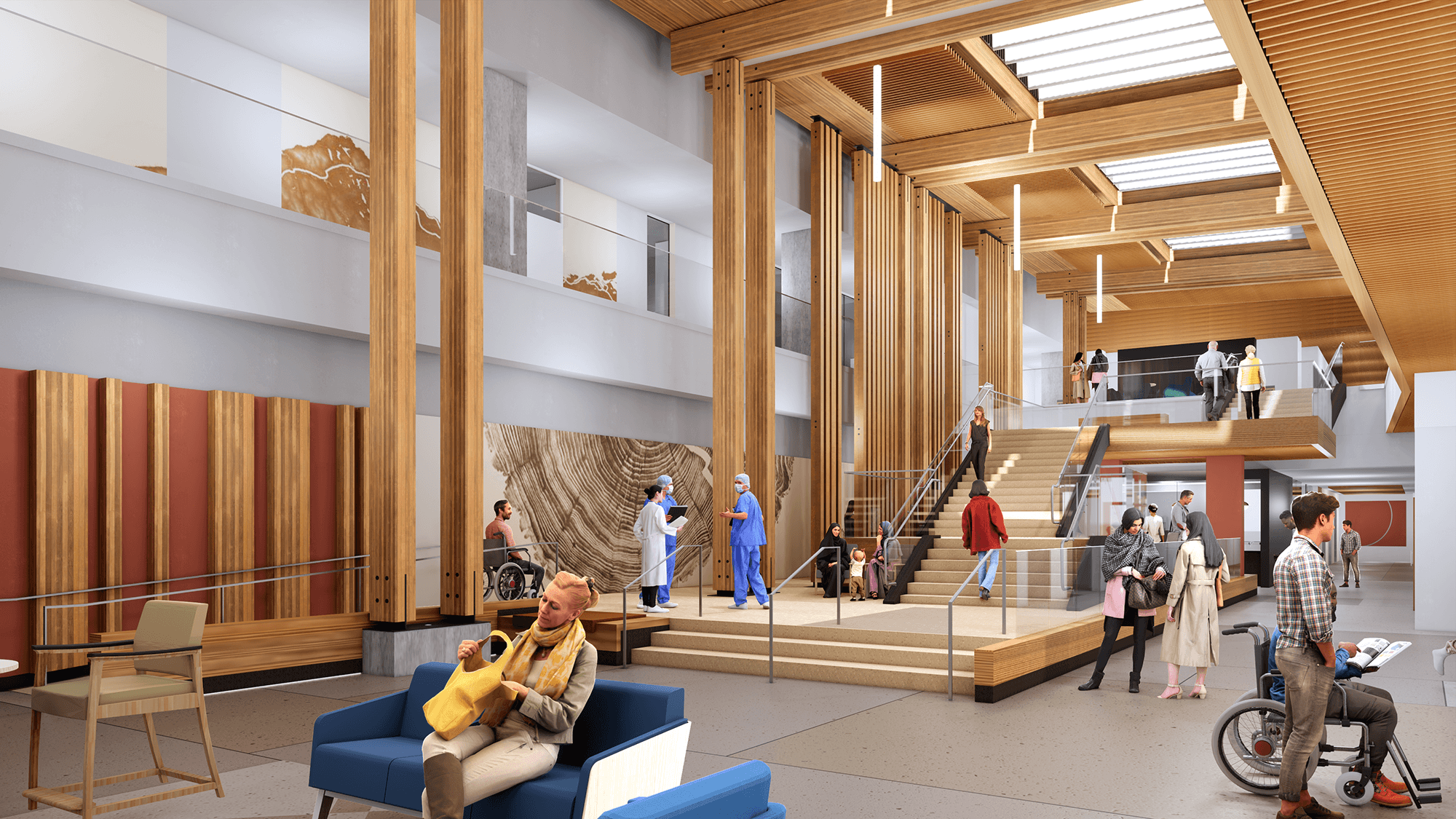

The endeavor, formally called the Cowichan District Hospital Replacement Project, will yield a 7-story hospital partially made of heavy timber. The nexus of the new building will be the 2-story heavy timber community hall that connects the future Diagnostic and Treatment Block and the Inpatient Tower. The architects note that they worked closely with Indigenous Nations to ensure the hospital building is culturally sensitive and significant to the local community.

Shane Czypyha, a principal at Parkin Architects, told AN that the hospital design draws from lengthy meetings and discussions with representatives from Cowichan Tribes. “It began with an invite to the project leadership by Cowichan Tribes for immersive cultural education at the outset to learn about cultural safety as well as their customs, and our entire design and project team has participated in cultural safety training as well,” Czypyha said.

“We have leaned on this education while conducting many engagement sessions and meals with local elders, language experts, Indigenous food experts, the Indigenous health advisory council, regional nations leadership groups and the general public through journey mapping sessions,” Czypyha continued. “The format of the process was Indigenous led, has involved regular feedback sessions, and our learnings from these engagements has resulted in a design by Parkin and ZGF Architects which responds to the customs and needs, reflects vernacular architecture and culture, and involves the participation of the local Indigenous community.”

The new building will be three times larger than the existing hospital. It will have 204 beds, 7 operating rooms, 2 trauma bays, rapid access and discharge space, fast-track streaming space, and a dedicated acute psychiatric zone. In Canada today, regulations mandate that only one room in any given hospital should be equipped for Indigenous healing customs that involve burning, but the architects behind Cowichan District Hospital exceeded that minimum. Of the hospital’s 204 rooms, 185 will be capable of healing practices that involve burning.

The hospital will also have generous patios that offer sweeping views of Cowichan Valley. To ensure people feel comfortable entering the space, the triage desk design tucks the security office out of sight, and the security personnel’s name was changed to “Ts’uwtun” which means “greeter” in the Hul’q’umi’num people’s native language. This practice is meant to make sure visitors are met with a “welcoming and trusting face that is devoid of punitive connotations,” Parkin Architects said.

At Cowichan District Hospital, the architects seek to build Canada’s first carbon-zero hospital, and British Columbia’s first all-electric hospital. To reduce medical errors, all patient and support rooms will be standardized. Washroom layouts will be optimized to minimize staff injuries, and hand hygiene sinks are being relocated from support rooms to corridor entrances in order to enhance visibility, and encourage better hygiene practices to reduce hospital-acquired infections.

Construction has begun on the replacement building, and Cowichan District Hospital is slated to open for patient care in 2027.