Regardless of its overpowering sense of genuine radicality, invention, and novelty, the Paimio Sanatorium addresses us through all of our senses, including the muscular sense of movement and sense of touch. Paradoxically, through its very radicality, it also awakens our sense of history and the evolution of culture. Here the experiences of place and self turn into a singular experience, and we send our self being strengthened and benignly empowered.

— Juhani Pallasmaa, keynote address, 2023 Spirit of Paimio conference

As a young man, the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto spent several days in the hospital. As he lay in bed, he dreamt of a new subject for architecture: “The Horizontal Man,” a hospital patient whose perspective would become the basis for his revolutionary Paimio Sanatorium in Paimio, Finland. Completed in 1933 in collaboration with his wife Aino, the hospital is one of the finest examples of functionalist architecture and was almost certainly the nicest and most comfortable sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB), a respiratory disease of global epidemic proportions that plagued the first half of the 20th century.

Sanatoriums were hospital complexes specifically designed to provide isolation, fresh air, and natural light to TB patients going through months-long battles to survive. Architecture was at the core of this mission. Aalto’s “Horizontal Man” pointed to an architecture of particular care. The sanatorium’s rooms were designed so that light, color, heating, and sound would provide comfort, especially for patients lying on their backs. Paimio’s dark-painted ceilings prevent eye strain, while lights placed out of the view do not cause glare. This dialogue between our environment and our bodies has resonance today, as cities become more hostile and technology continues its relentless distortion of the public sphere. Paimio Sanatorium is a reminder of how design can be part of a better vision for the future: one where care is taken for ourselves, for each other, and for society at large.

These questions—admittedly large ones—are at the center of the Paimio Sanatorium Foundation’s recently reinvigorated mission to recast the complex as a center for culture, education, and wellness. Mirkku Kullberg, the foundation’s CEO, and Joseph Grima, its curator, convened a conference in October featuring some of the leading figures in culture, design, and preservation today to think about what it might mean to continue Paimio’s legacy as a “manifesto for an architecture of empathy, care, and human dignity.”

With all the cultural and civic value embedded in the Paimio Sanatorium campus, it’s an enormous challenge to steward the site. Like many important architectural heritage sites, adaptive reuse is necessary to breathe new life into the buildings. A plan to rebrand as a health and wellness retreat is on the table, and the Paimio Foundation plans to raise some €40 million. The plan is ambitious. The seven-story main building will contain 146 hotel rooms, converted from hospital rooms. Several sauna spaces keeping with the visual language of Aalto’s 1933 structure will be central amenities, taking cues from “medical hotels” that go beyond the typical spa experience. This may create new audiences outside luxury design enthusiasts—beyond boutique.

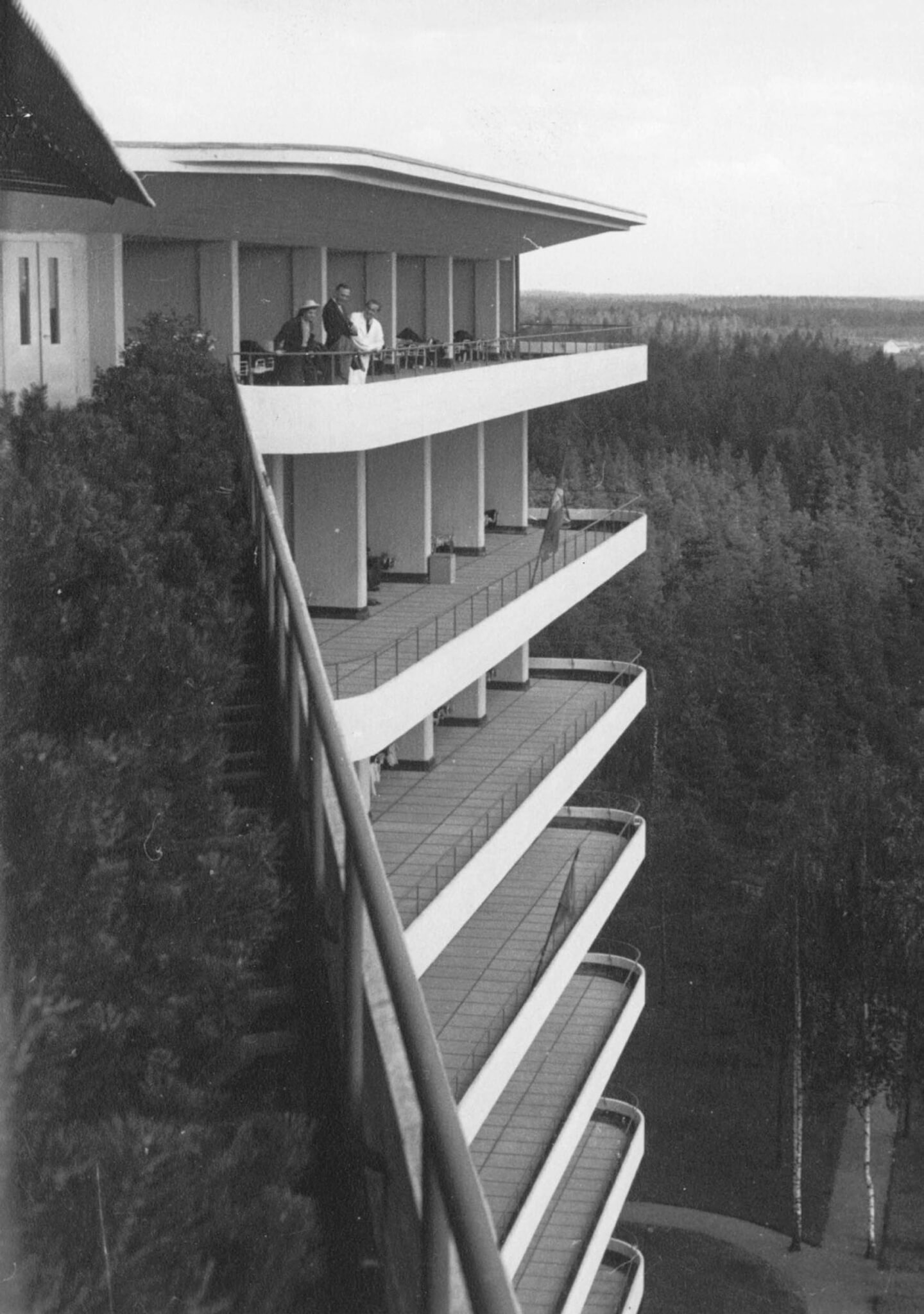

Tuberculosis patients at Paimio were not to be envied, but they did get to sleep outside in fur-lined sleeping bags on a rooftop terrace overlooking the Finnish pine forest. This Nordic tradition of creating spaces in harmony with nature and surrounding ecosystems no longer is a matter of life and death, but it represents a new way of caring for ourselves. Visitors will be able to sleep under the stars on newly restored terraces, and extensive gardens will offer locally grown food.

In October 2023, the first Spirit of Paimio conference featured leaders in design and culture, including architect and adaptive resume expert Lyndon Neri, technologist Otto Lowe of the Factum Foundation, director of the Amos Rex Museum Keiran Long, and many other speakers who discussed the myriad issues that Paimio conjures, from adaptive reuse to digital conservation, to institution building and national identity. Finnish architect and theorist Juhani Pallasmaa gave a keynote address and received a lifetime achievement award. A second conference is planned for October 2024.

It is the first in many such programs that will transform the remote location into a destination beyond what it already is. Can a hotel survive off architecture students on study abroad sketching trips? Will design hotel enthusiasts be alright with sharing a bathroom? Because of the protected status of the building, the interventions must be minimal. These will not be luxury hotel rooms in the traditional sense. Thus, a different “community,” as Grima described—born out of a different culture—must be identified at Paimio beyond architectural tourism. Situated at the intersection of health and design, the hotel will also provide opportunities for “medical tourism,” curated treatments and gatherings around new trends in wellness hospitality such as “sleep tourism.”

Paimio embodies Aalto’s quest for an architecture connecting man, nature, and building. Aalto in his time broke with the staunch modernists of the CIAM and the Bauhaus: his horizontal man offers a degree of specificity that Le Corbusier’s modular man did not. While the modular man was a falsely universal subject that could be repeated ad infinitum to produce any architecture, Aalto’s horizontal man is a speculative subject intended to connect the building and the patient in a specific, highly attuned relationship. It cannot be stressed enough how important the precedent of Paimio’s generous, humane design is in an era of ruthless automation, big data, global neoliberalism, and generic, placeless architecture that often disregards human experience outside of performance metrics.

In this way, Paimio has potential to become a test site for many of the most prescient issues of our time. Although it has its own unique Finnish characteristics, it shares much in common with sites of cultural heritage with cult followings, such as Arcosanti, Burning Man, the town of Columbus, Indiana, or even the region around Marfa, Texas. These places are constantly reinventing not only their physical surroundings, but the communities and events that take place there. As Pallasmaa said in his address, Paimio presents us with “the dignity and welcoming gestures of the architecture and the promise of good care and healing.” How to reimagine an already special place into the contemporary version of these ideals is an exciting proposition.

Matt Shaw is a New York–based critic and faculty at SCI-Arc.