In 2021, California passed Senate Bill 9 (SB9), a statewide law that allows single-family lots to be split into two lots, with each resulting lot rebuilt or converted into two housing units. Given that there are over 300,000 single-family lots in Los Angeles alone, the potential for SB9 to unlock access to much-needed housing is hard to overstate.

Yet, in the first year that SB9 went into effect, the City of Los Angeles permitted a scant 38 Senate Bill 9 housing units, which was still the most out of any city in California.

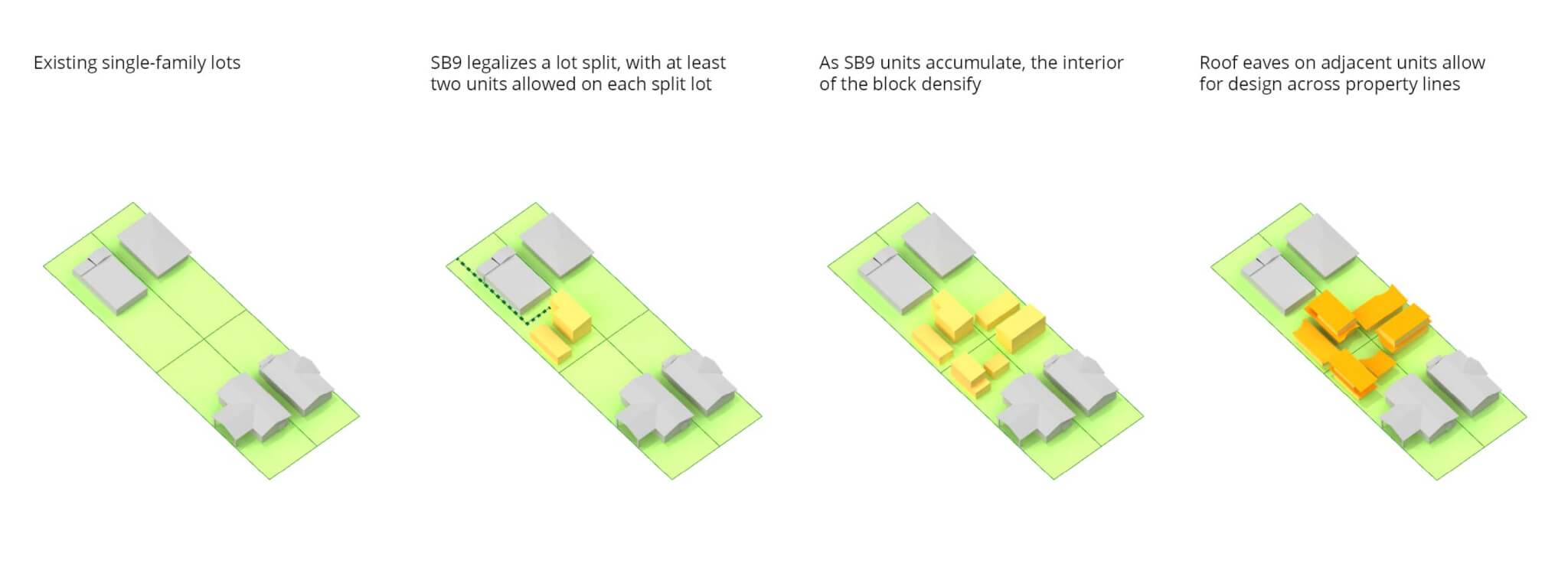

SB9, also called the California Housing Opportunity and More Efficiency (HOME) Act, was envisioned to“strengthen the fabric of our neighborhoods with equity, inclusivity, and affordability.” It was supposed to create new housing in the vast expanses of land zoned only for single-family homes across California cities. Under SB9, an existing single-family lot can be split into two lots. Each split lot can be rebuilt with two units, with additional units possible if local jurisdictions allow it. Parking requirements are eliminated if the lot is close to public transport or a car-share. In simple terms, SB9 is a tool for multiplication through division, acting in direct counterpoint to the minimum lot size requirements that propelled sprawl.

So why hasn’t SB9 seen wider use? For one, homeowners and builders have struggled to navigate the legal and financial protocols to build with SB9. According to a study by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation, local jurisdictions have implemented additional regulations on SB9 projects, including size and height limitations. Moreover, SB9 ventures into unfamiliar territories of reconfiguring existing single-family residential fabrics, which begets hesitation from homeowners and opposition from neighbors. Homeowners in affluent cities are organizing to stop SB9, bringing cases to court and seeking historic district statutes to forestall SB9 projects. Still, there are glimmers of interest from homeowners exploring SB9 to achieve a diverse range of housing goals, from downsizing to intergenerational living.

SB9’s apparent woes lay bare the fact that it is still relatively new and untested. In contrast, ADU legalization has been mandated on single-family lots in California since 2016. Every year since, ADU construction has been made more accessible through both policy change and design intervention. It has become an impactful force of housing creation in California and a wellspring of innovative work for architects. If architects and planners can experiment with and advocate for the design merits of SB9, it can garner similar support. The spatial, social, and political complexities of the lot split can act as the medium for more imaginative ways to live together. While the adoption of ADUs has enabled compelling projects that plug into existing lots, the compounded density encouraged through SB9 is a wholly different project that requires rethinking the lot and, by extension, the residential block.

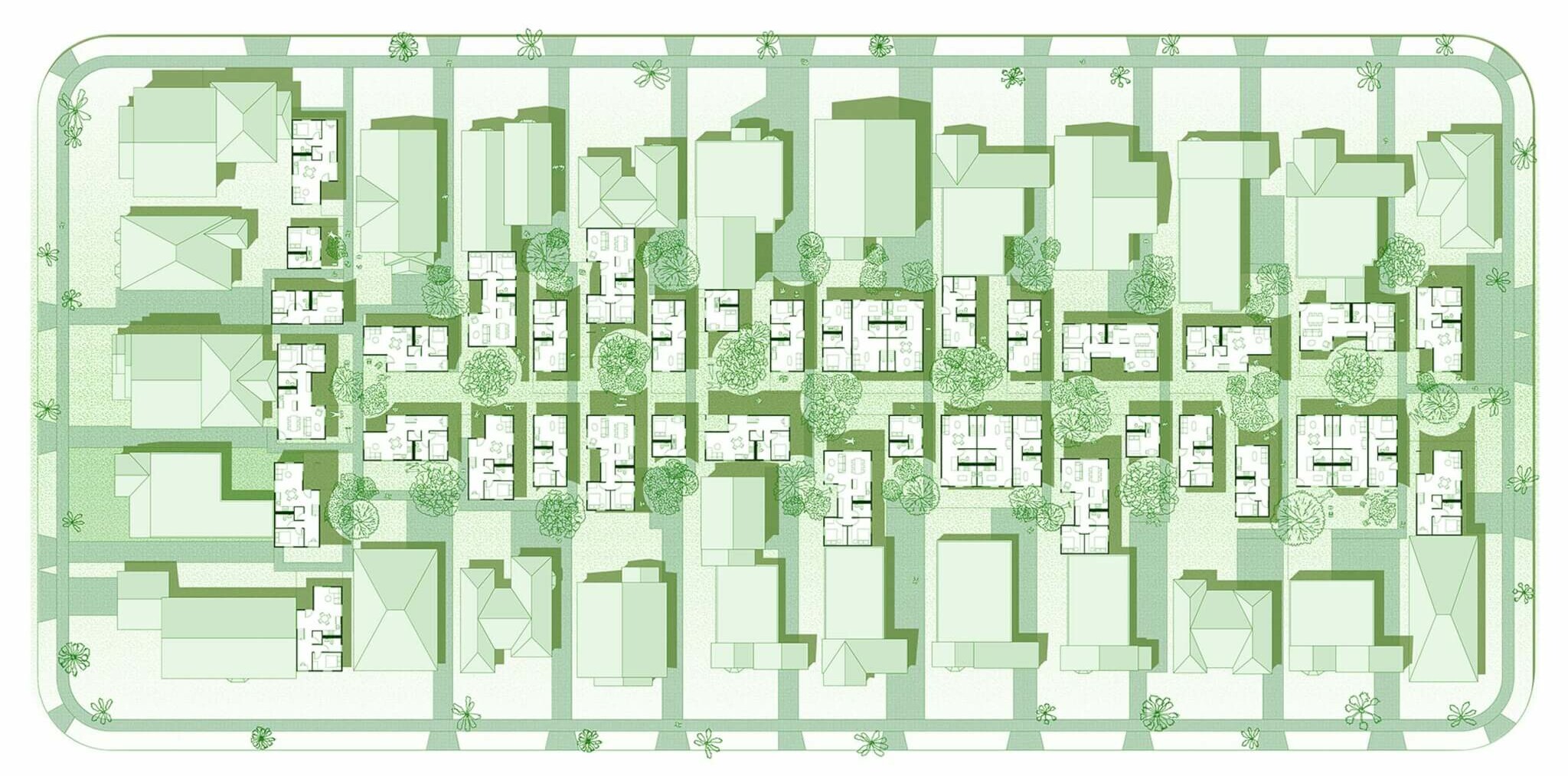

To open this conversation, our research and design practice Rebuild Collective proposes the Courtyard Block, a reimagining of a typical R1-zoned residential block in Los Angeles that can be built now under SB9. The Courtyard Block evolves the block’s existing rigid grid of individual backyards into lively arrangements of courtyards that can be shared between neighbors. In doing so, it addresses one of the main design challenges of SB9: As lots are divided and units multiply within a confined block, access to open space becomes a precious asset. The traditional backyard, facing and serving a single unit, becomes untenable. A courtyard, however, is a form that faces multiple sides and can serve multiple units.

Rather than a fixed proposal, Courtyard Block is a design tool: a collection of architectural parts negotiated through top-down regulations (SB9) and bottom-up aspirations (mutually beneficial agreements between neighbors). The courtyards in a Courtyard Block are not enclosed, but rather implied through the curvature of roof eaves and the changing shadows they cast. While the eaves create visual and spatial connections, their shadows go even further by crossing property lines. The unassuming roof eave, a vernacular feature that provides shade and directs rainwater, is elevated as a desirable and attainable tool for building cooperation between neighbors.

Courtyard Block sets in motion a transformation of land use across property lines through a feedback loop between the design, residents, and new protocols over time. The plans can accommodate incremental change, mirroring the way that ADU and SB9 laws work because of their reliance on individual agency. It adheres to SB9’s setback rules, but also challenges the notion that lots must stay separated. It offers residents the ability to preserve individual space, but promises something better if space is shared for the benefit of the collective.

For more than a century, residential blocks have been confined by restrictive zoning and used as what the Othering and Belonging Institute calls “a mechanism of opportunity hoarding.” By designing beyond the private lot and moving toward a collective block, we can start to move the needle on urgent challenges through design imagination. Designers can and should be using their platforms and skills to create new pathways for change, and ultimately demonstrate what is possible if residents, city officials, and developers work together. It’s time to build better blocks.

Courtyard Block was researched and designed by Rebuild Collective: De Peter Yi, Peter Loayza, Heather Cheng, and Owen Sims, and received an honorable mention in the Los Angeles Affordable Housing Challenge.

De Peter Yi is assistant professor of architecture at the University of Cincinnati, and founder of Rebuild Collective, an architectural research and design studio.