The first panel of this week’s conference at Columbia’s GSAPP, “Permanent Change: Plastics in Architecture and Engineering,” got down to business a few minutes late on Thursday morning. After a brief welcome, Dean Mark Wigley ceded the floor to Michael Bell, the first speaker in the line-up for “The Emergence of Polymers: Natural Material–Industrial Material.” But the pace picked up as Bell and subsequent presenters took listeners on an intense romp through the role of plastics in architectural history, providing background for the nine panels to follow through Friday evening.

While each presentation had a distinctly different focus, there were a few standby slides that popped up in more than one powerpoint. The Vinylite House from the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933 made repeat appearances, the Smithson’s House of Tomorrow got props from more than one presenter, and Mansanto’s House of the Future at Disneyland took the prize for most mentions. We got a chance to sit down with one presenter after the panel discussion.

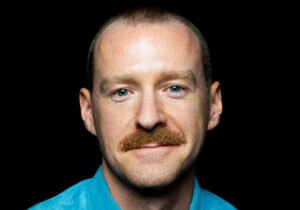

Billie Faircloth is the research director at KieranTimerberlake in Philadelphia. In her presentation she discussed sifting through more than 75 years worth of architecture journals. “I was interested in understanding how a material emerges as a building material,” she said. “And with plastic it was possible because of its relatively short history, unlike masonry.” Faircloth scoured library bookshelves and her own collection of trade journals. She used a “transect” method of collecting data. For a scientist studying a particular species in the field, transecting means that the researcher maintains a fixed path to observe the number of times the species appears. In this case, the path was paved with twelve architectural journals. “The only way to track this was through the architectural press and journals,” she said. “I thought of them as a set of evidence. One can get a front row seat to a very narrow venue.”

The first mention of plastic was in a journal from 1933. Journals from 1954 to the early 1960s yielded the most data, as by that time the National Academy of Sciences was pushing for research on plastic use within the field of architecture. MIT, the University of Michigan, Illinois Institute of Technology and Washington University in St. Louis all held conferences on the subject and the architectural press was on hand.

The variety of plastics in Faircloth’s study included dozens of trade names and distinct chemical compositions, but all fell under the deceptively simple moniker: plastics. “They’re really thousands of materials, but for convenience we use only one word,” she said. For the early period of the study, only 25 varieties of plastics were named; by the early 21st century, that number ballooned to 134. But alongside all the cross-references and transects (all beautifully mapped), Faircloth began tracking repeated words and phrases. She compiled yet another list. “Three phrases were repeated, no matter time or disposition of the author,” she said. “’Plastics are difficult to decipher.‘ ‘Plastics are not substitute materials.‘ ‘Plastics are the future.‘”