In 1902, the under-known Prussian architect and author, Hermann Muthesius, promoted what he labeled Sachlichkeit, prior to the prophecies of his seminal Austrian contemporary, Adolf Loos. It summarized a design philosophy that advocated the “elimination of every merely decorative form,” giving way only to “form according to demands set by purpose.”

Endeavoring with fin-de-siècle fervor to shape how a new century could build, Muthesius declared that “ornament” would exist only if endemic to the overall conception of surface and materiality rather than as some extraneous froufrou that groped back at a severed past.

Loos later solidified his place as modernism’s harbinger with his more dogmatic credo: “Freedom from ornament is a sign of spiritual strength … (it) cannot any longer be made by anyone.”

The design platform for Europe and the Americas at least seemed fixed. Ornament gave way to “decoration” shaped by the personal choices of the end-user. Architecture’s task was best fulfilled when separated from art and replaced by the more practical assignment of delivering comfortable utility: The proverbial machine for living and a blank state of decoration with ornament led to its further devaluation, despite its former centrality to place making.

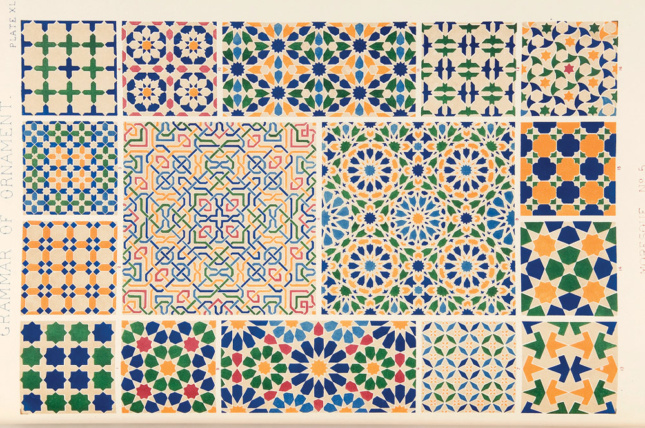

As this important volume reveals by concentrating on the greater Mediterranean basin of Christian Europe and the fluctuating contours of the Islamic world (descending from the classical Greek suzerainty and its successive Roman Empire shaped by Vitruvian aesthetic orthodoxy), the debate is far more nuanced. The case is made that—in built reality—no break with ornament ever fully took place, despite the intent and ethos of the modernists. Like history itself, ornament did not end in the 20th century but merely evolved with renewed force, ultimately from postmodernism’s backward glance.

Histories of Ornament was inspired by papers delivered at an international conference held at Harvard in 2012. Whether translated or seamlessly edited by Necipoğlu and Payne, it covers an unprecedented and stringent collection of scholarly research and reflection. It is not a history of ornament per se, but rather a rigorous and sometimes cautionary record of the history of ornament’s shifting meaning and theoretical basis. This volume assesses ornament as a legitimate aspect of designing the future built environment.

It is neither elegy nor encyclopedia; the purpose instead is summed up simply in the editors’ introduction as “to address what ornament does [and did].” The result is a summons to surrender preconceived notions about ornament as somehow apart from or inferior to architecture in its full range of possible expression.

Despite varying assessments by the diverse contributors on the present state of ornament, the book is enlivened by an acknowledgment that it owes part of its resurgence to the digital tools available in this still young century.

In Part I, “Contemporaneity of Ornament in Architecture,” the scholar Vittoria Di Palma acknowledges that even traditional ornament, such as that of the classical orders (so long removed from any underlying structural imperative) remains off limits to progress, while new technologies are both jumpstarting and inventing many others. Overall exterior surface patterning rendered essential to core architectural intent has been made feasible in ways that Edward Durell Stone or Frank Lloyd Wright were striving toward a half-century ago.

Di Palma reminds us, however, that “technology is not the wellspring of desire” and considers how other forces, distinct from the historic, religious, or nationalistic narrative, drive ornament’s return. Among her conclusions is their root in sensation and how “by operating on a biological level, by privileging the body and its forms of knowledge, both its affect and effect hold out promise of a potential universality.” In this way, globalization and its gradual imposition of common expectations across cultures emerge as an opportunity for shared sensation.

The sections build the case that while ornament often served as a signal of some victorious cultural imposition, the result was its absorption and adjustment leading to new, assimilated meanings.

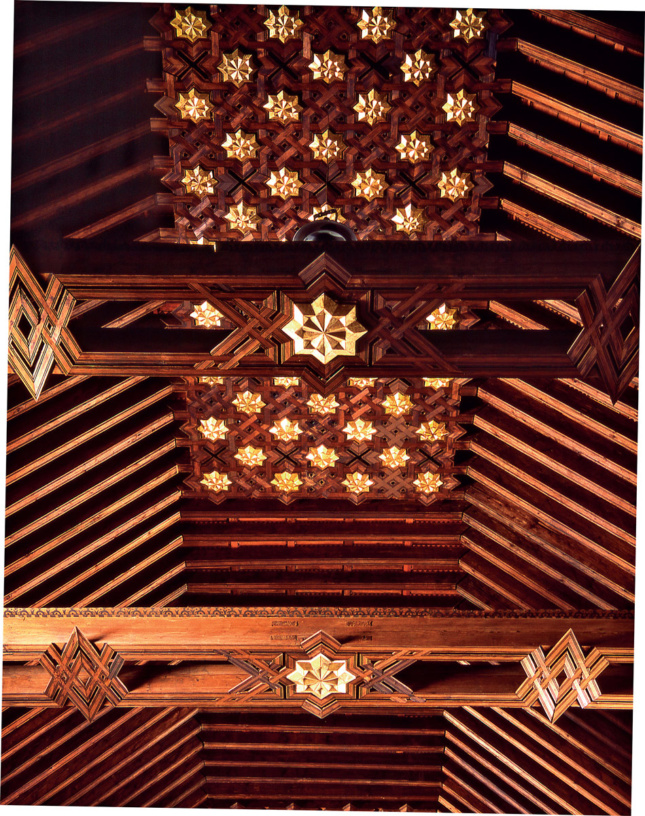

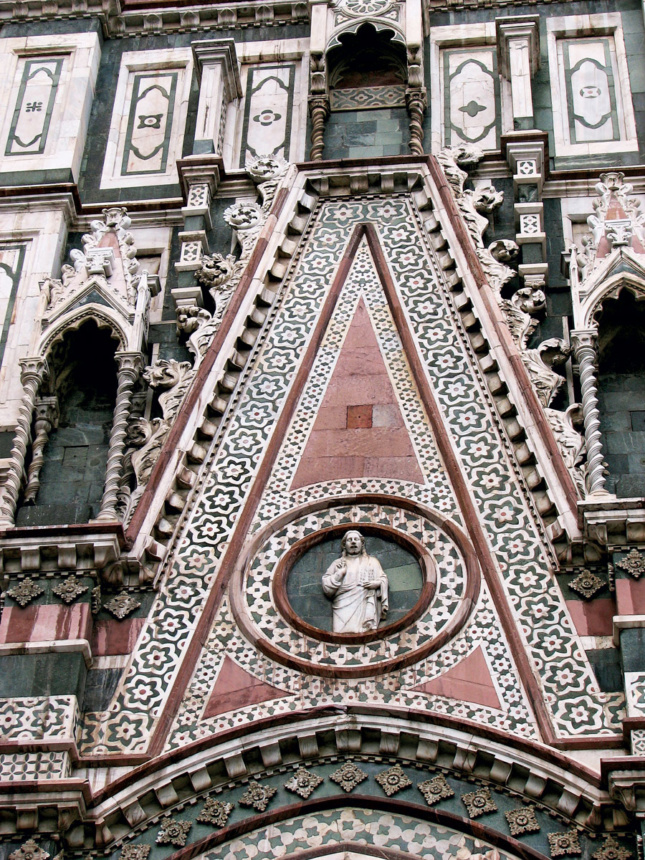

In chapter six of the polemical Part II, “Ornament between Historiography and Theory,” scholar Maria Judith Feliciano examines the conceptual and syncretic

invention of Mudéjar design by the revisionist 19th-century art historian, José Amador de los Ríos, who invented a label for the profound place of Islamic design ornament on the Iberian Peninsula. He transmuted the historic impact of seven centuries of regional Moorish control and, above all, the Arabesque expression of its distinctive ornamented architecture into a metaphor of ultimate Catholic vindication.

Feliciano explained, “De los Ríos defined it as a reflection of the grandeur of the Christian national character, which was capable of effecting conquest, tolerating diversity, and demanding the artistic and intellectual participation of its citizens in the construction of a productive enlightened state.” In other words, the act of ornamental expropriation defined in terms of cultural and political submission underscores the inevitable goodness of a unitary monarchy. In the 20th century this led to its successor, the Fascist Francisco Franco. Franco’s minster of fine arts went farther still in pronouncing that Spain was not only the foremost agent for extending the Catholic religion and the past glories of Rome, but also “the transmitter of the artistic culture of Islam in the New World…which in an effort unparalleled in history was discovered and conquered by Spain, and by her was incorporated in the Occidental and Catholic culture.”

Ornament takes its place as the characterization of civilization’s advance whether good or evil.

Rather than being superfluous, ornament reclaims its design role freed from normative narratives. Its utility shifts not only in its application, but also in its innate, essential meaning for both contemporary practitioners and occupants alike.

In the architecture of today, Sachlichkeit gives way to Gesamtkunstwerk. Muthesius and his cohorts did not so much get their wish, as they set the stage for design theory

and its built yield as a new vocabulary characterizing ornament’s essential place in architecture.

Humankind relies on sensation to thrive, rather than merely survive.

Histories of Ornament

Gülru Necipoğlu and Alina Payne, Princeton University Press, $60