With perspective comes power, and a fun-filled, quirky demonstration of this can be found in Disappear Here at the Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA) in London, courtesy of British architect Sam Jacob and curator Marie Bak Mortensen.

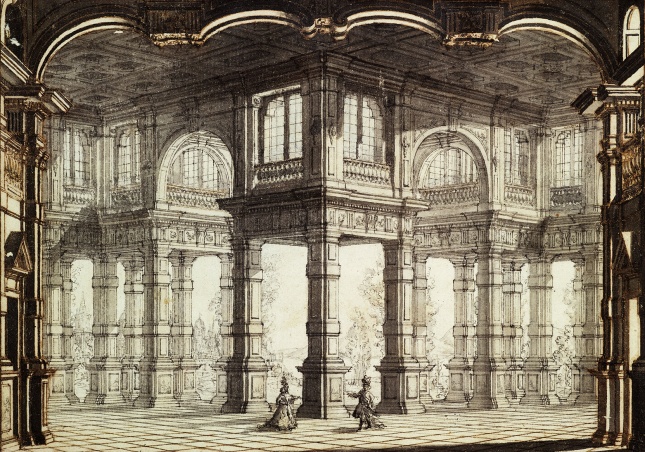

Disappear Here greets visitors with a vestibule of turquoise tones. Faux entrances, layered like a theatre set, recede in height and hue in a nod to the techniques employed by Renaissance painters who used light shades of blue to indicate depth in paintings. Before this, however, it was Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi who, in the 1400s, discovered linear perspective as a system of drawing and thus brought science and art in a collision that gave birth to the Renaissance.

However, none of Brunelleschi’s work is on display. Half a millennium after the Italian master’s existence, Florence, his home town, had produced more architectural superstars: Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Adolfo Natalini, Gian Piero Frassinelli, Alessandro Poli and brothers Roberto and Alessandro Magris who comprised Superstudio. The firm’s work, earmarked by grid motifs, is featured throughout Disappear Here with two mirrored wells (great for peering into and taking a selfie), and two drawings: Un Viaggio nelle Regioni della Ragione (A Journey to the Realm of Reason) and Graz. The latter links up with a rare, albeit mediocre, perspective drawing done on the back of another—supposedly much more impressive piece—from Andrea Palladio.

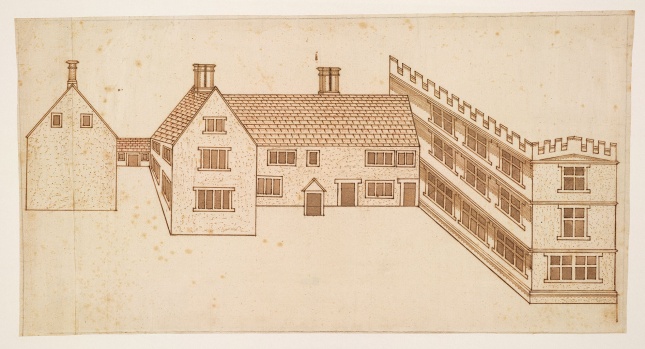

For one wall, Jacob and Mortensen’s method was to marry drawings through their lines of perspective, imagining their continuation off the page. This link would be easily missed if not for an explanation in an accompanying leaflet, which also provides a tutorial on linear perspective drawing. Jacob, though, was excited by what he could do using this method of arrangement. “It’s brought together works which should never belong next to each other,” he told The Architect’s Newspaper (AN). Case in point: a pair of trolls urinating into a castellated fountain, drawn by British architect John Smythson, sits below Superstudio’s Un Viaggio nelle Regioni della Ragione, which in turn lies left of a sketch by Edwin Lutyens portraying an unrealized memorial in France. The eclectic trio of drawings makes for remarkable viewing, and the wall throws up some humorous examples of failed attempts at perspective representation, such as another drawing by Smythson, this time of a skew-whiff house. However, the arrangement system means Palladio’s drawing is placed awkwardly high. For those taking their children, you can tell them not to lose sleep over missing out on this one.

However, shift your gaze down, and you’ll find that the baseboard is mirrored. This has the effect of making the floor seem like an infinite plane, an effect which is amplified by a grid of yellow dots that Jacob has added onto the floor.

In another room, the fun for all ages continues. Fifty objects fly towards and past the viewer on three projections cast onto walls in front and on either side of you. The objects follow lines of apparent linear perspective and create the sensation of hurtling through a drawing. To Jacob, who worked with game developer Shedworks for the exhibit, “it feels like experiencing a drawing through time.” Here, the impact would be far greater had projections filled the floor and ceiling or virtual reality headsets been used. Jacob told AN that he explored the possibility of using the latter, but in the end, decided against it.

A final room presents a collection of six books on perspective drawing, all from RIBA’s rare books collection. Abraham Bosse’s Mr. Desgargue’s Universal Method of Practicing Perspective (1648) is opened up to show a drawing of three figures looking down with pyramids coming from their eyes and making a square on the floor: a view of their perspective, so to speak. Jacob, when showing AN around Disappear Here, argued that this depiction of perspective mimics the view from a modern-day military drone. Sadly, this connection isn’t made in the actual show, and other ties to more contemporary takes on perspective, besides the collaboration with Shedworks, are awry. Jacob and Mortensen’s insight into the history of perspective, intertwined with quirky illusory tricks, fails to exhibit work of any contemporary architecture firms. Jacob, who is more than aware of contemporary architectural techniques of representation, particularly collage, even noted that a few pasted people could turn one drawing into a typical piece from Portuguese firm Fala Atelier or architects Point Supreme from Greece.

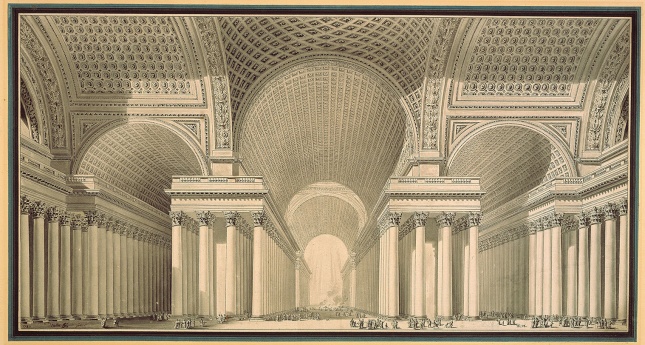

For all the allusion to progressing off the page and into the infinite, the supposed “power” of perspective, well documented in an essay by Jacob found inside the exhibition’s leaflet, is also found wanting. Aside from the discombobulating decor, which does make Disappear Here fun to navigate, French architect Étienne-Louis Boullée’s fantasy cathedral (see lead image) is the only piece that shows audiences the awe-inspiring power of scale and perspective at work.

Superstudio’s arguably most famous conception, Il Destino del Monumento Continuo (Destiny of the Continuous Moment), would fit nicely here. It, along with other works from Superstudio and other Italian radicals of the era, however, can be found at the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal where Utopie Radicali: Florence 1966–1976 is currently on view. For more exercises in disorientation, Sean Griffiths, a co-founder alongside Jacob of now defunct British studio FAT, has also been exploring perspective techniques in London and Folkestone.