When British landscape architect Nicholas Bonner set out for North Korea’s capital, Pyongyang, in 1993, he anticipated a gloomy concrete metropolis. However, on the flight there, brightly colored sugar and pepper condiment packets hinted that a more florid environment lay in store. Fast forward 25 years and Bonner is offering tours of Pyongyang to visitors, including The Guardian‘s architecture critic Oliver Wainwright who documents the candy-colored city in his new book, Inside North Korea available August 15 from Taschen.

Wainwright only spent a week inside North Korea, but that was sufficient time to take enough photographs to fill a 240-page book. “Every day was jam-packed,” Wainwright told The Architect’s Newspaper. The photographs along with an introductory essay shed light on what is a typically closed-off country that has strict rules for journalists. Though he was shepherded by three guards at all times, Wainwright was afforded more freedom by traveling as a tourist instead of a journalist and was able to document Pyongyang’s built environment through a point-and-shoot camera.

The images, particularly the interior shots, could easily be stills from a Wes Anderson movie. Interiors are laid out symmetrically, with portraits of the former North Korean premier, Kim Il-sung, and the former Supreme Leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-il, typically hanging at the focal points of the room. Their presence is no accident. According to Kim Jong-il’s 160-page treatise, On Architecture, “the leader’s image must always be placed in the center of the architectural space,” a dictum which is carried through with regulations that stipulate that nothing else can be hung on the same wall as these portraits.

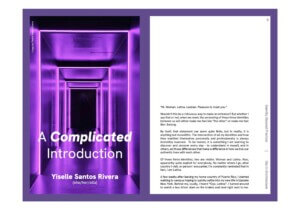

Perhaps the most dazzling interior is that of the East Pyongyang Grand Theatre seen above. Originally built in 1989, it can hold an audience of 3,500 people. A 2007 renovation brought the theater up to Grand Budapest Hotel standards with plaster moldings, scalloped peach-colored walls, purple upholstered seats, a bright-blue vinyl floor, polished stone tiles, and a huge mural relief being added. Images of the theater and other interiors can feel staged, which Wainwright acknowledged while saying everything was shot “just as it is.”

Images of leadership are used even more emphatically outdoors. Streets have been organized to maximize the effect of these portraits, which Wainwright describes as “utterly crushing, giving the impression of a street made for giants.”

The world’s largest bronze statues of people can be found at the top of Mansu Hill. Looking over a stone plaza, 66-foot-high statues of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung peer onto the Monument to Party Founding situated at the end of an axis one-and-a-quarter miles away. The two former leaders stand in front of a mosaic and are flanked by giant red granite flags which are propped up by bronze workers. One has a plaque which reads: “Let us drive out the U.S. imperialists and reunite our fatherland!”

For a country so focused on image, it’s unsurprising to learn that it has tried to scrub all foreign influences, U.S. imperialism included, from its aesthetics and architecture. “An architect who is convinced that his country and this are the best will not look upon foreign things or try to copy them, but make tireless efforts to create architecture amenable to his people,” wrote Kim Jong-il in On Architecture. Despite all this, images of architectural precedents could be found at the Paektusan Academy of Architecture where images of buildings from around the world could be found, from Moscow’s Seven Sisters to Terry Farrell’s MI6 Building in London.

In all, Pyongyang embodies North Korea’s approach to self-presentation: Big Brother-esque images that project the state’s power and ability to protect its citizens amplified at a bombastic scale and sweetened with saccharine pastels.

Inside North Korea

Oliver Wainwright, Julius Wiedemann

TASCHEN

$60.00