The streets of Stockholm are still littered with the fading colors of campaign posters from an undecided election. From the pink backdrop of feminist candidates, to progressive reds, conservative blues, and the struggling greens, to the slippery, slick gradients of the neo-nationalists. The politics of the public sphere have been unavoidable lately in Sweden, but a couple of heavy rains are slowly turning what’s left behind back into grey pulp.

Meanwhile, Value in the Virtual, an exhibit by London-based Space Popular, blossoms with a polychrome array of signs, patterns, and symbols. The show has just opened at Sweden’s national center for architecture and design, ArkDes, under new its director Kieran Long. A new feature of the museum is a smaller gallery space—Boxen, a steel box designed by local practice Dehlin Brattgård—inside one of the two main exhibition halls. It is intended for fast-paced architecture shows curated by former ArchDaily editor James Taylor-Foster, and Value in the Virtual is the first display of work by a contemporary design practice in the new setup.

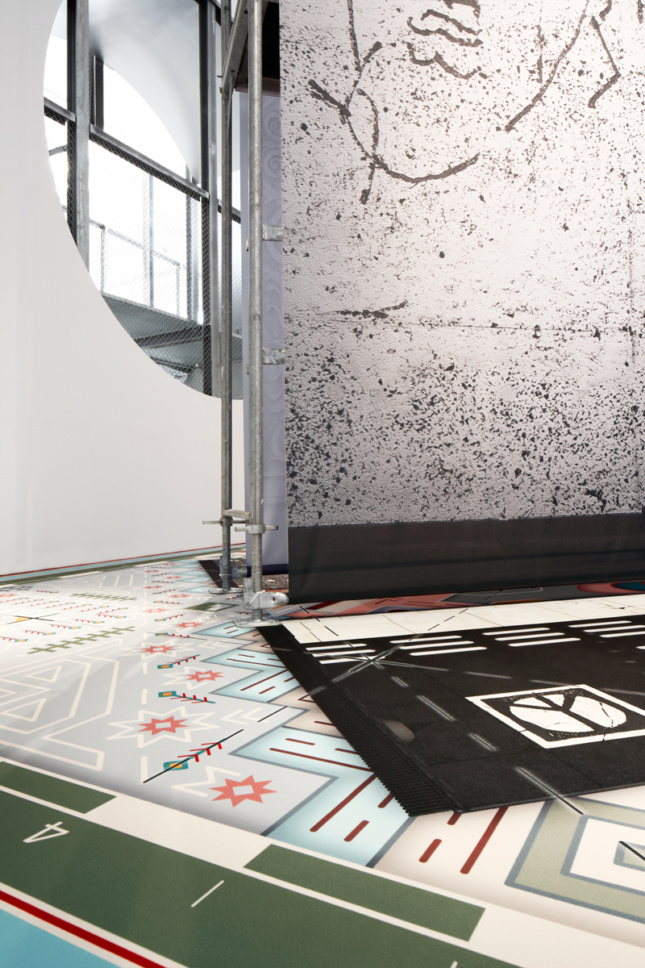

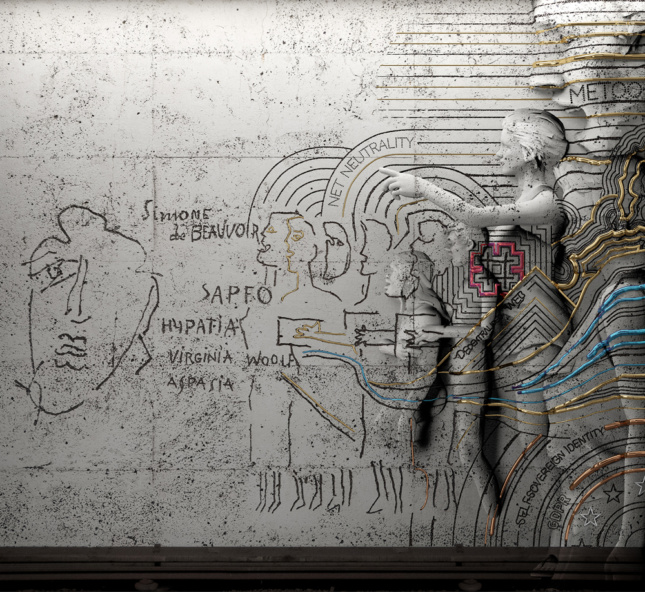

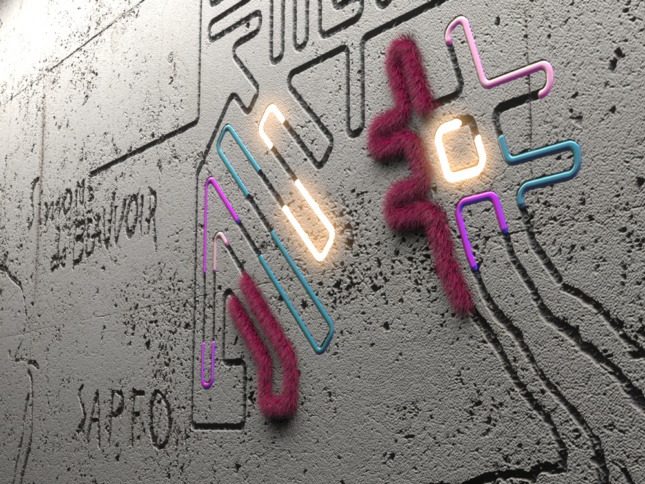

The Space Popular duo, Lara Lesmes and Fredrik Hellberg, have grabbed the opportunity to build what they describe as their manifesto. It consists of six “typical” Stockholm environments—a downtown apartment, a vintage-styled coworking café, an exclusive nightlife district, a banquet hall, an iconic subway station, and a royal park—retrofitted with an added layer of augmented reality. They are rendered in 1:1-scale elevations printed on tapestries and hung from scaffolding in cornered-off spaces. Each corner is a mash-up with “walls” from two or three locations.

Entering the exhibition space, you are invited to take your shoes off (to experience the printed carpets on the floors), and once inside, to put on a pair of virtual reality goggles. They are a window into Voxen, a parallel version of the same gallery space produced for Sansar, a social virtual reality platform. During the press preview, an online visitor had already found his way there for a peek. The avatar, dressed in a black bodysuit and a Daft Punk motorcycle helmet, showed up out of nowhere, mumbled a distorted “nice to meet you,” and soon disappeared.

In this realm, you get 3-D views of some of Space Popular’s scenarios: one is a version of Stockholm where public art is updated by the minute; in another the allegorical wall mosaics of the Nobel Prize venue are adjusted to tout recent scientific achievements; and in another a selective nightclub bouncer might actually let you in after all, if you upgrade to a nicer-looking “skin.”

For a casual visitor to be able to follow the narratives, though, some additional guidance would be welcome. Instead, the dense 3-D visuals are trusted to speak for themselves.

An argument underlying Value in the Virtual is that architects could, and should, engage with the potential digital depth of architectural surfaces, as well as what comes with it: cognitive psychology, color theory, and the techniques to manipulate it. The exhibit seems to say, “Get on with it and design your own digital tapestry for the scaffolding that is, for lack of a better word, the real world. And if you don’t,” the argument is, “somebody else will.” And when augmented reality hardware moves from “a drawer on your face” to a casual pair of glasses, virtual dressing of space, and the market for virtual real estate, could become a big deal. “What is the role of the architect and designer in this transition?” a section of the wall text asks, when designers are “not bound by a requirement to shelter” nor “to the various physical limitations” we are used to?

Either way, many architects are already engaged. Architecture school graduates, especially in the United States, are increasingly recruited by software companies before they even contemplate a career as licensed master-builders. Architecture is already part of the $137.9-billion gaming industry market, but perhaps not in familiar ways.

The exhibition wants to look at what is going on while augmented reality is still in its infancy and to figure out the consequences of the tech before it is sitting on everyone’s face.

Will visitors get it? Do the chosen scenarios illustrate what is actually claimed to be at stake? What is the real promise here? What is the threat? This stuff is touched upon in the exhibition brochure but not very evident in the exhibit itself. And if the argument is made more clearly in writing in Space Popular’s ten-point programmatic declaration, what does the gallery display add, except a VR demo and an institutional seal of approval? Maybe that’s enough. It’s a start to the conversation Space Popular wants us to have.

Stockholm is normally very neat. Putting up posters is prohibited, and the rules are generally abided by. Political campaign material is the exception, and come election season, the city is carpeted with colorful platitudes and slogans.

Public space is already a kind of virtual real estate, a moderated social medium that is regulated, traded, and hacked. It always has been, you could argue. Sure, the visual exploitation of it is augmented by new technologies, but the question, then, is if that augmentation does something that didn’t happen before.

The politics of augmentation are not that different to the conflicts of interest, power plays, and negotiations of spatial politics already being debated. A peephole into another world can make you forget where you are standing at the moment. Sometimes, a mirror would perhaps be more useful.

Space Popular: Value in the Virtual, curated by James Taylor-Foster, is on view at ArkDes, Sweden’s national center for architecture and design in Stockholm through November 18, 2018.