MALL stands for Mass Architectural Loopty Loops or Miniature Angles & Little Lines, among other variations. Just like its ever-changing moniker, MALL’s work is constantly shifting. Founded by Jennifer Bonner in 2009, the Boston-based studio develops collections of projects that iteratively build from one to the next. As a graduate of Auburn University’s Rural Studio and Harvard Graduate School of Design—where she currently serves as faculty—Bonner channels her love of the American South and uses her teaching to experiment with new typologies and invent new modes of architectural representation.

Her colorful, out-of-the-box approach to design is just one of many reasons why she is named one of AN Interior’s top 50 interior architects. AN associate editor Sydney Franklin spoke with Bonner about stepping away from tradition and what’s next for MALL.

AN Interior: What would you say are the driving forces behind your aesthetic project?

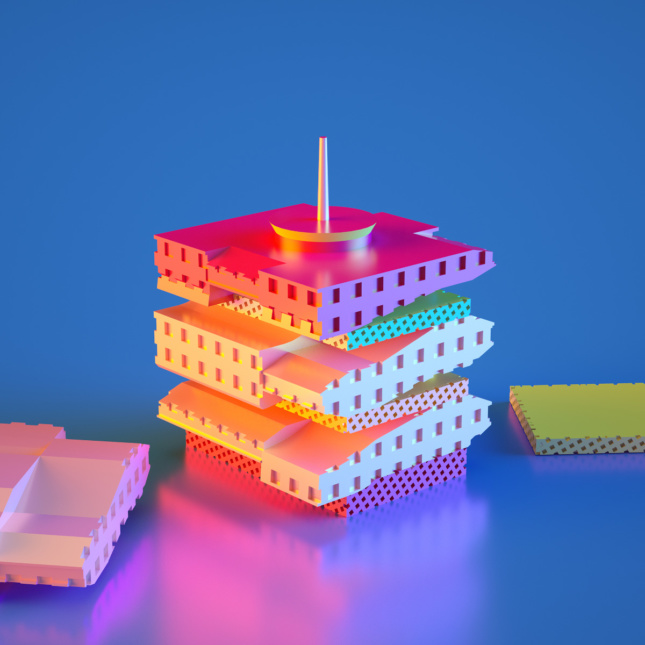

Jennifer Bonner: As you probably noticed from looking at my work, each of the projects are very different formally. At MALL, we begin by working on a conceptual and intellectual project first, and the formal emerges out of these considerations. I am against producing an overall “MALL aesthetic” and much more interested in many architectures. Yet within a single project, the process I’ve set up for my office is to work through many iterations around singular ideas—never discarding any, but creating a cute collection. You can see these collections in the work of Domestic Hats and Best Sandwiches. The latter is a colorful spatial experiment questioning how architecture might stack, in which we are interested in reimagining the extruded midrise office tower.

AN: So these collections allow you to explore multiple new typologies?

JB: Each of my larger conceptual projects has the potentiality to question paradigms, which is what I’m most interested in. Take the roof forms in Domestic Hats and Haus Gables, a single-family house opening this month made from one of the original Domestic Hats models. I believe the roof plan can be an instigator of space rather than using Le Corbusier’s free plan and Adolf Loos’s raumplan. Here I was looking to expand different roof typologies, which is a topic I dove into while teaching at Georgia Tech.

AN: You’re also keen on expanding your use of unique materials, textures, and colors in your formal projects.

JB: Yes, I really want to keep pushing the boundaries of materiality. I’m currently working on this through a project called Faux Brick, a distant cousin to the Glittery Faux-Facade study I developed in 2017. In preparation for this year’s Bauhaus Centennial, I’ve studied a pair of houses by Mies van der Rohe in Germany where I argue that authentic bricks are used as a fake structural strategy. In this project, we’re trying to figure out how the rendering and other representational techniques involving bad bump maps and bad meshes might create new faux-brick facades.

AN: How has your experience teaching and living in different places like London, Istanbul, Los Angeles, and Boston informed your work?

JB: As someone who has one foot in academia and one foot in practice, it has been exciting to absorb all of these cities into the way I imagine architecture. Having grown up in Alabama and recently living in Atlanta, I have decidedly made an effort to work on architecture in the American South. It is not by accident that my first architecture, Haus Gables, is located in Atlanta.

AN: For Atlanta, Haus Gables is a really avant-garde residential design. It’s made of cross-laminated timber and features quirky exterior and interior finishes. How were you able to make it so different?

JB: It’s completely self-funded without a traditional client—so my partner and I have taken on all of the risk. It was important for me that the design be as radical as possible in my first built work, and not diluted by many external factors. Radical, however, does not mean there wasn’t a fixed budget (which there certainly was). Throughout my career, I’ve worked with several clients associated with the public realm, such as institutions and galleries, but that kind of client is different from, say, a client who wants you to design a house.

AN: So you want to design and develop your own projects too?

JB: I wouldn’t call myself a developer just yet. But I’ve always been into what John Portman did in Atlanta in the 1960s as an architect who both developed and found financing for his projects. By doing this, he was able to produce a new typology, the super atrium, which I’m not sure he would have been able to accomplish so early in his career if he had faced typical constraints.