“We are in pursuits of an idea, a new vernacular, something to stand alongside the space capsules, computers and throw-away packages of an atomic/electronic age,” Warren Chalk, member of former British architecture studio Archigram once said. Chalk’s quote epitomized Archigram’s outlook and approach—daring, brave, looking firmly into the future, and slightly tongue-in-cheek. Archigram and its contemporaries of similarly brilliant names (Ant Farm, Superstudio and Archizoom) have since been canonized as being part of an elite group of supposedly Avant-Garde architects. But if that was the crème-de-la-crème of 50 years ago, what is the equivalent today? Re-imagining the Avant-Garde, on show at Betts Project in East London, might have the answer.

If you want to see some good drawings, this is the place to go—not surprising given the star-studded exhibitor list: Ant Farm, Pablo Bronstein, Peter Eisenman, Sam Jacob, OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen, Jimenez Lai/Bureau Spectacular, and Aldo Rossi, to name a few, are all on show and none disappoint. Neither do the smaller studios: UrbanLab, WAI Think Tank, Warehouse of Architecture and Research (WAR), and Office Kovacs. Those exhibited are either mentioned in or have contributed to a special edition of AD Magazine which takes the same name as the exhibition at Betts Project. British duo Matthew Butcher and Luke Pearson, both academics, writers, and designers guest co-edited the magazine and co-curated this exhibition.

“Avant-Garde” used in relation to architecture today brings to mind the work of Archigram et al., all of who sprouted from the fervent experimental ground of the 1960s and ’70s. It’s through this moment in architectural history which Re-Imagining the Avant-Garde attempts to frame contemporary architectural practice and thought.

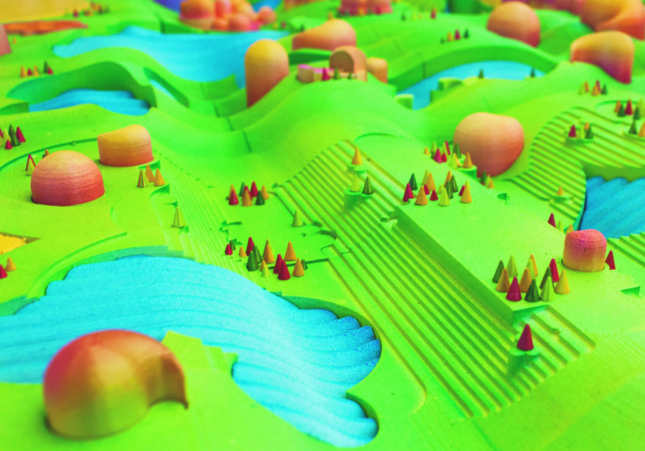

So how does the historical and contemporary sit next to each other? Rather comfortably, it turns out. As images and models, all arguably fall under the umbrella of Pop Architecture; British critic Reyner Banham’s definition holding true. Take Belgium firm Office Kersten Geers’ Border Wall, for example. The studio helped popularize the collage style of architectural representation a few years ago and it’s a useful medium for Border Wall. Here it is employed to highlight tensions between territories—in this case, a walled forest in the middle of a desert divided by a fence. The desert landscape is a blurry image, while the tree trunks are conveniently hidden, all of which consequently obfuscates any sense of scale, adding a layer of ambiguity to the piece.

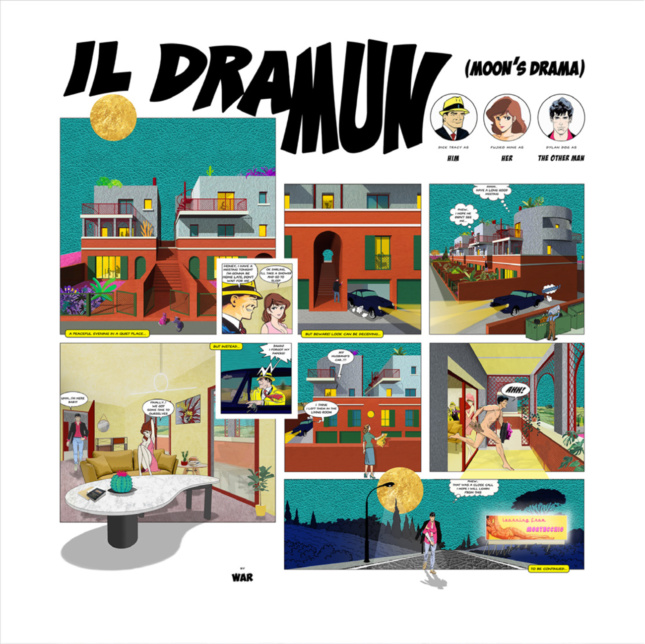

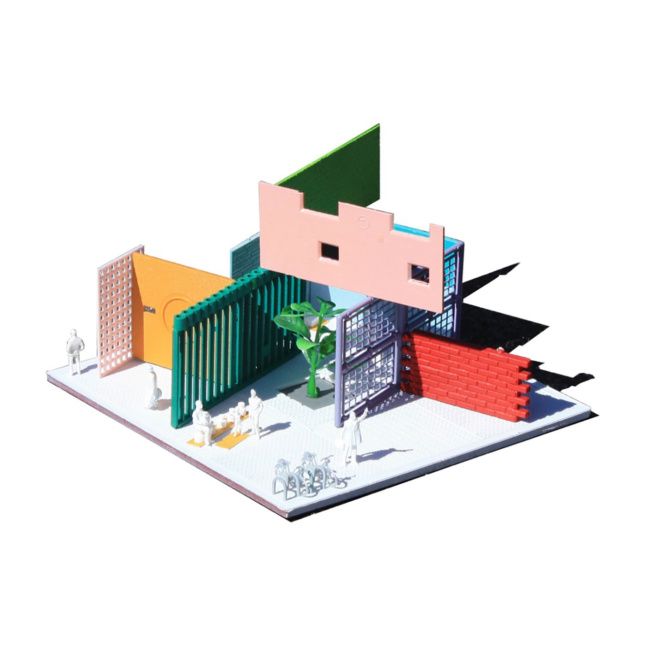

Other exhibitors reference the Avant-Garde architectural canon explicitly, like WAR for example, who projects its architecture through a comic strip akin to the drawings of Archigram. L.A.-based Office Kovacs, run by Andrew Kovacs, meanwhile provides a palimpsest of readymade architectural artifacts in Miniature maze, a work that draws on the archive of affinities found in Kovacs’ blog of architectural b-sides.

As these works are displayed next to photos of Ant Farm’s famous touring truck, and with other ’60s radicals in mind, it’s evident that the contemporary practices on show are producing work that is just as visually arresting as their predecessors. But what’s the difference between then and now?

“Yes, ’70s utopian groups have influenced us—it’s obvious, no? The difference is that we work out there in reality,” Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius of the Berlin-based raumlabor told AN editor-in-chief William Menking in his article for the issue of AD Magazine.

Like all good exhibitions, Re-imagining the Avant-Garde provokes more questions. Is this the Avant-Garde reimagined? Why are we being asked to re-imagine the Avant-Garde in the first place, is it the hope of stumbling upon another wave of Avant-Garde architects? Very few, if any, realize they are part of an Avant-Garde, even if they have Avant-Gardist ambitions (see Chalk’s quote). The term is, for the most part, applied through a historical lens. We only realize there was an Avant-Garde once it has been and, sadly, gone. We might even find that the more we search for an Avant-Garde, the more it will evade us.

When Abbot Suger worked with his Master Masons on the Basilica of Saint-Denis in 12th-Century France, he probably didn’t expect the Gothic-style church he commissioned to end up defining the built landscape of Medieval Europe. Far less did Suger realize that he was part of an architectural Avant-Garde (or equivalent seeing as the phrase emerged some 700 years after).

Defining a historical Avant-Garde imposes restrictions on a supposed contemporary Avant-Garde. Also writing in the same issue of AD Magazine, critic Mimi Zeiger argues that “The work of Italian radicals Superstudio [and others] provides endless fodder for appropriation,” which is the case with much the work on show at Betts Project. Furthermore, the elite Avant-Garde club which Butcher and Pearson refer to is essentially an all-white gentleman’s club. “Re-imagining the avant-garde might seem celebratory at first but unless radically re-contextualized and critiqued, it can be a trap. Old biases and omissions are reinforced: canons crystallized, hierarchies hardened, patriarchal practices protected,” adds Zeiger.

In light of this, instead of aspiring to be part of an Avant-Garde, today’s architects should forget about the term altogether and strive to make a more sustainable planet. Much as how Chalk imagined building for an “atomic/electronic age,” a similarly forward-thinking vision will surely prove to be Avant-Garde in time.

Re-imagining the Avant-Garde runs through December 21.