A few months back, while casually scrolling through some feed or another, I was struck by a series of images for a Portland-based boot company, Danner. Kicking up a faint cloud of dust with measured, deliberate steps, a lone photovoltaic maintenance worker moves across the image between parallel sets of solar trackers in a 64-acre facility in the high desert landscape just outside of Bend, Oregon. Emblazoned in bold over the image, the word “STRONGHOLD” conjured the work-boot family and the attitude of the region from which it springs. In what could pass for a Green New Deal campaign lifted from only the most heroic of WPA posters, other images from the commercial shoot evoke the photovoltaic maintenance process—a delicate operation involving technical expertise, careful stewardship, the right boots “built for comfort and stability,” and a Dodge Ram with plates reading “1932,” Danner’s date of establishment prior to relocating to Portland, where it would supply loggers with caulked boots during the Depression. From those origins spring the current slate of boot categories: work, hike, lifestyle, hunt, military, and law enforcement, producing an uneasy space where aesthetic cohesion and mythologizing coagulate in an open wound of mixed messaging between bright green and militarized versions of the future. The Danner website declares: “The Future Is Strong.”

Scenes like the above are a renewable resource in the Pacific Northwest, underwritten by a low-key utopian sense that’s as much about a “way” of doing things as it is about place. Oregon is of the American West, but not exactly the center of its mythos. In the estimation of the 1940 Federal Writers’ Project guide to the state, Oregon’s position at the “end of the trail” leveraged terminus into an exceptional charge that “inspire[d] not provincial patriotism, but affection”: “The newcomer at first may smile at the attitude of Oregonians towards their scenery and their climate. But soon he will begin to refer to Mt. Hood as ‘our mountain.’” Here, the “dismal skies” and rains of winter were merely the “annual tax” one paid for the privilege of inhabiting a state of “eternal verdure”—a cozy picture that excludes the desert land east of the Cascades mountain range and a whole host of volcanic and seismic activity lying in wait and prone to violent outbursts.

For its part, the city of Bend has recently been deemed a commuter town for Silicon Valley and is an increasingly expensive playground where brewpubs, rec centers, inner tube flotillas on the Deschutes River, and extensive parkland make their own kind of lively stronghold at the base of the Three Sisters Mountains. As in Portland just on the other side of the Cascades, there’s a rolling collision between earlier imported and newly imported visions of an affluent good life in nature that are just complementary enough to exist in tenuous détente while other narratives vie for recognition.

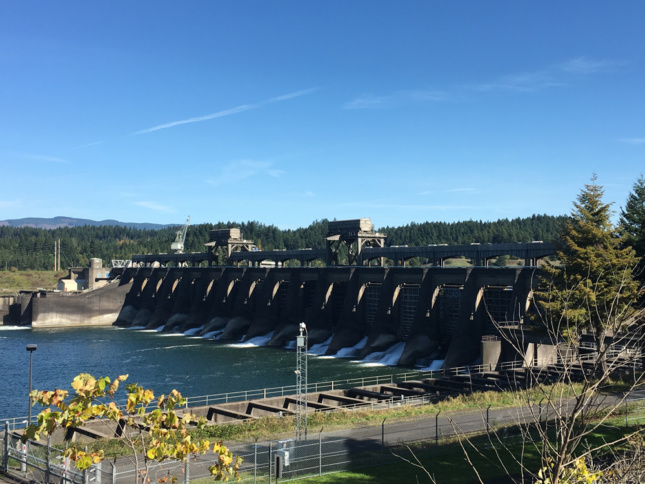

Upon arriving in Portland by way of a westward drive through the Columbia River Gorge, it was hard for me to escape the impression that this working landscape had been staged as an advertisement for the achievement of a kind of augmented reality just removed from the usual roiling of time. The B Reactor at Hanford, Washington, and the still-toxic ghosts of the Manhattan Project were out there somewhere, as was a Lamb Weston facility that processes 600 million pounds of frozen potato products annually, but here in this gash through the Cascades was a vision of forward movement in balance. Flanked by wind turbines running along the hill crests and with Hood’s emblematic peak directly ahead, rail and moss-lined roadways delivered a parade of works and features, from dams, locks, and spillways to waterfalls and elevated viewpoints. Some of these projects, like the Bonneville Dam, have been held up as pivotal but imperfect New Deal–era models of public hydropower administration, while The Dalles Dam is known more for its erasure of Celilo Falls, once a critical center of indigenous cultural and economic life. Such erasure and fragmentation, however, are far from the exception, as white nationalists have also long found refuge in Cascadia’s crevices and realty boards since the state’s founding in black exclusion. Here, too, the American Redoubt and various Cascadian secession movements pick up where Ernest Callenbach’s more countercultural 1975 novel Ecotopia left off with utopian search/seeking, be it for an ecotopia or a white nationalist stronghold.

As a perverse addendum to the theme of exclusion, however, Oregon’s urban growth boundaries have made for a compelling regional planning model, containing sprawl to preserve the “natural” playground and its biodiversity. In all things a kind of balance. Runaway utopian-as-utilitarian dreaming was, after all, the villain of California-born author Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1971 novel, The Lathe of Heaven, a fable of Portland’s exceptionalist attitude and the relative wealth of its natural inheritance. In this corner of the country, there was the possibility, for some, of a more comfortable—or less uncomfortable—future. Still, the novel’s status as a critique of progress or a privileged and resigned version of the same remains difficult to discern.

Storied weirdness aside, Portland is one of several metropolitan centers with the self-designation, “the city that works.” And it does, though critiques of the “sustainable city” are rolling in from those willing to cast a more critical eye toward the externalities and displacements produced through progress of this sort. Persistent NIMBY-ism and the ongoing battle over a proposed I-5 expansion amid new reports that Portland’s carbon emissions reduction progress has flatlined since 2012 suggest that the city’s climate policies are still far from where they need to be. On a more positive note, Oregon HB 2001’s move to effectively dissolve single-family zoning was the kind of course correction one would come to expect in the wake of new evidence of housing need. As with other improvements over its history—UGBs, public ownership of the coast, mass timber innovation by firms like LEVER and Hacker, ecodistricts, hydropower, cycling culture, and transit-oriented development—in paving the way for a proliferation of duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes, Oregon again models a quietly progressive version of a future.

Exemplary care-oriented building projects also come to mind, like the Seven Corners Collaborative in Southeast Portland, where Waterleaf designed a new, fully accessible colocation center for local nonprofits that provide support services for people with disabilities, along with an assistive technology lab for training, consultation, and public interface. Elsewhere, in the Lents neighborhood, a shelter in the repurposed shell of an old church forms the heart of a new “family village” campus by Jessica Helgerson Interior Design, Carleton Hart Architecture, and Corlett Landscape Architecture that’s furthering the use of trauma-informed design and concentrated service delivery for families experiencing homelessness. Also in Lents, the new Asian Health & Service Center by Holst provides a venue not only for much-needed affordable healthcare services for the area, but also a well-appointed infrastructure for community social events, all granted a generous view of Mt. Hood from the top floor. SCOTT | EDWARDS ARCHITECTURE’s Portland Mercado fulfills a similar social function for Portland’s Latinx community through a modest adaptive reuse and landscape strategy that ties an existing structure together with a series of food carts, covered outdoor space, and copious seating. Led in part by the efforts of the latter two firms along with Ankrom Moisan and organizations such as Home Forward and Central City Concern, recent supportive housing projects in the city, such as Bud Clark Commons, the Beech Street Apartments, Garlington Place, and the Blackburn Center, are also demonstrating how architecture can operate and innovate through a lens of care and playfulness rather than singular virtuosity or brute force.

This ethos also comes out in Portland’s new and renovated green spaces, such as the collaboration by 2.ink Studio and Skylab on Luuwit View Park in East Portland. The park stands as a microcosm of the city’s celebrated urban landscape innovations, complete with community gardens, dog park, skate park, event shelter, public art, stormwater treatment area, and bilingual signage to acknowledge and accommodate the diversity of new residents in the neighborhood, as well as trails aligned with distant landmarks like Mt. St. Helens, or “Luuwit,” as named in the Cowlitz language. Likewise, with Cully Park in Northeast Portland, 2.ink explored similar design elements on the site of a former landfill in an underserved neighborhood, including significant habitat restoration, a fitness course, and the city’s first Native gathering garden. Developed by the community nonprofit Verde in partnership with the city, the project engaged neighborhood residents throughout the process with outreach, employment, and education programs.

More broadly, a host of design and planning-based initiatives work to translate reparative sociopolitical agendas into spatial terms, such as the Portland African American Leadership Forum’s 2017 People’s Plan and the more recent Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability publication on the Historical Context of Racist Planning in the city. Blocking pipeline projects and filling streets in the name of climate action, Sunrise, XR, and 350PDX also stake active claims on the city and its future, while newly constructed works like FLOAT’s Portals in Southern Oregon stage direct action pipeline resistance, countering fossil fuel extraction logics with an expansive meditation on architecture’s capacity to support multispecies reciprocity. Further, initiatives and organizations throughout the region like Columbia Riverkeeper, Sightline, Wisdom of the Elders, the High Desert Partnership, and the Ashland Forest Resiliency Stewardship Project engage in environmental care and land management through advocacy and cross-scalar collaborations, while efforts by the Friends of Trees and the city’s Green Street Steward Program involve volunteers in urban greening and bioswale maintenance. On the academic front, Portland State University’s Center for Public Interest Design was founded in 2013 to respond to the needs of underserved communities in the city and abroad and has since paired design-build work with robust community engagement processes, while the University of Oregon has launched a multidisciplinary fellowship initiative in Design for Spatial Justice, which mobilizes theory and practice in foregrounding narratives, experiences, and modes of design, political action, and biodiversity conservation long marginalized or excluded by fields responsible for the built environment.

How this expanding constellation of projects and practices might fare in an escalating climate struggle is a crucial question. With even cursory estimates of climate-induced in-migration to the region due to sea level rise alone projecting numbers in the hundreds of thousands over the next few decades, the challenge for utopia would initially seem to be one of scale. The war footing rhetoric of the GND, like that of the New Deal before it, anticipates such scales of action in the work of justice and infrastructural investment. A war footing for scaling care, however, is perhaps a more fraught and paradoxical charge, particularly as the goal would be to move beyond a narrow definition of relief as an improvised response toward the construction of more durable and equitable systems merging care with justice.

In a dysfunctional climate regime, what does it mean to position oneself as a stronghold or a refuge, or a model city? When PG&E issued its now-infamous directive to its California customers to “use your own resources to relocate” when the utility company unilaterally shut off power to nearly a million people back in October, it signaled that climate change survival would become a matter of self-reliance if left in the hands of those with no obligation for care. Against this backdrop, even a modicum of external accountability would come to appear as care and competency. As Holly Jean Buck writes, “There are plenty of scenarios where we deal with climate change in a middling way that preserves the existing unequal arrangements…[where] even muddling through looks like an amazing social feat, an orchestration so elaborate and requiring so much luck that people may find it a fantastic utopian dream.” In a global theater of sociopolitical and ecological degradation, it becomes difficult to assess the utopian potential of projects that work well within familiar registers, leading in some cases to a privileging of expediency and the reenactment of functioning models.

But, even with the relative risk aversion, what bridges the perceived cultural gulf between the measured and occasionally errant strands of progressivism in the Pacific Northwest and the most fanciful Silicon Valley fever dreams is the recurring belief in some level of remove as a precondition for positive transformation and mastery. The right person in the right boots in the right geography, and a comfortable future is assured. The inclusion of photovoltaics in that picture is a welcome addition, but what is the future of an image like this in a present where what’s demanded is both a dissolution of the concept of human mastery over the environment and a dramatic mobilization, reorientation, and upscaling of progressive instruments closely aligned with the tools, attitudes, and systems that delivered the environment to the brink of collapse in the first place? Its violence veiled as much as romanticized, the story of a pioneer harnessing the productive power of a landscape was one promise of “the West.” As many of Oregon’s latest projects begin to suggest, there are and should be others, and the next steps are critical in defining the kind of refuge the region will become.