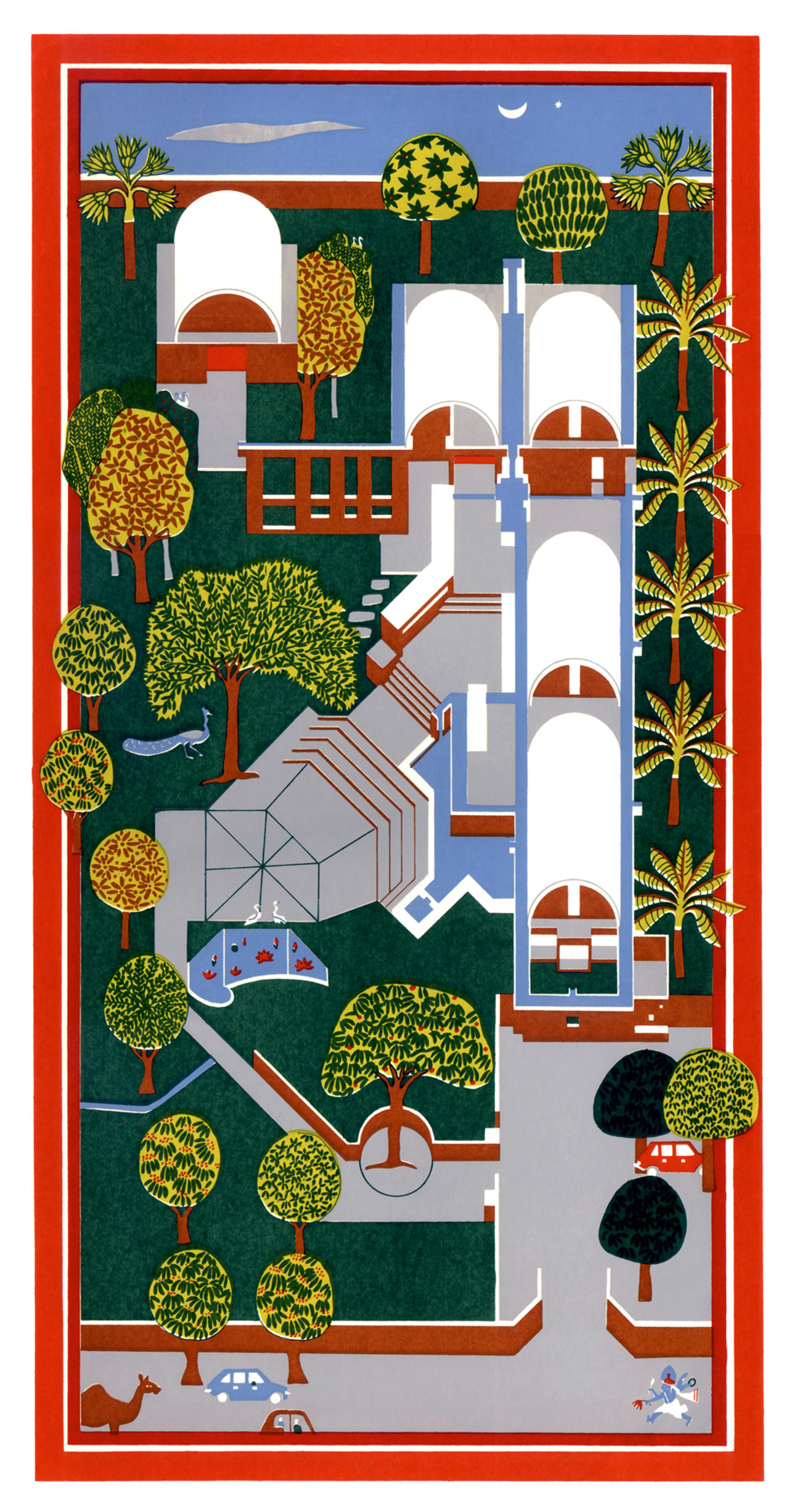

It’s truly fortunate that the Tadao Ando-designed–Wrightwood 659 gallery behaves as the Japanese architect’s other buildings do—with meticulously worked solid forms becoming receptacles for light and air—because Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People threatens to overwhelm. Not shy of big gestures, the exhibition announces itself to visitors via a gigantic silkscreened drawing of Doshi’s Ahmedabad, India, studio, signaling the way up into the first floor of galleries.

With its swaths of red, maroon, yellow, sky blue, and forest green, the print sings loudly against the backdrop of industrial Chicago brick and Ando’s telltale concrete, imbuing both with an added dimension. This is a modernism that’s precise, yes, and smart, and efficient, but, before any of that, deeply human.

I sense a cliché.

Before visiting the show, which had the support of a coalition of institutions including the Vitra Design Museum, Wüstenrot Foundation, and Vastushilpa Foundation and is on view at Wrightwood through December 12, I spoke to someone who had seen it. The most striking thing, they reported, was the presence of people in the architecture. In some ways, it’s baffling that the people-in-architecture motif could still be striking after so many years of disciplinary attempts to return “agency” to the people using buildings. Over time, that protracted campaign had the effect of splitting the discipline’s focus into two directions—toward an architecture that’s “about people” and an architecture that’s “about architecture.”

Balkrishna Doshi’s work defies that binary, and the show’s Wrightwood incarnation (the show originated at the Vitra Design Museum) makes that starkly clear. The presence of the human is everywhere, and the architectural spaces depicted in the various media—bronze-cast studies and incredibly precise sectional models rub elbows with drawings and paintings—exude a certain generosity. Which imbues which? For Doshi, the Pritzker Prize laureate and perhaps India’s most famous modernist architect, it comes down to perception.

Use types, not chronology, define the order of the displays, moving from spaces of learning to those of institutions (with a digressive brief look at Doshi’s city planning efforts), and finally culminating in the smallest, most personal scale of all—housing. Large models—sometimes made of wood, which reveals each wrong and right move of its maker, and sometimes of Styrofoam, easily dirtied, stuck together with tape, marred—and drawings in ink and pencil on paper stand in for the architecture. As do the photographs, which are large, roomy, taken from 5’6” off the ground and maybe several yards away. The aspect, highly effective, matches the visitor’s.

This clear human perspective makes the work, and therefore Doshi’s ethos, easily accessible. The formal variety, both in terms of the architecture itself but also in the representational repertoire on display, reveals Doshi as someone completely unafraid to try on new ideas, shapes, concepts. In the first section of the show, a right-angled building at the School of Architecture at the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology in Ahmedabad leads, non sequitur–like, to a composition of breast-like domed forms for the art gallery Amdavad Ni Gufa in the same city. They could be mistaken for the work of different authors. But the common thread here is not formal exploration; rather, it is a commitment to an architecture that gives shape to human activity without ever imposing on it.

Architects sometimes tell an anecdote about Le Corbusier’s India works (in whose execution Doshi played a pivotal role), that people used the brise-soleil on certain buildings to hang clothes out to dry. Depending on who tells it—I’m not sure which version is true, if any is—the point of the story is that Corb’s architecture simply hadn’t accounted for how people lived. It’s another cliché: the typical modernist architect, designing for other architects and not for people.

The inverse of this cliché, the one I sensed walking into Wrightwood, is that of the Global South architect, designing for people and not for other architects.

Taking in Doshi’s collected works, the clichés fall away. The human and the built work in conjunction. The point of architecture is to house, or to illuminate, or to connect, and none of those things are possible without people.